Our brains sculpt each other. So why do we study them in isolation?

Minds may best be understood as they exist, in social settings

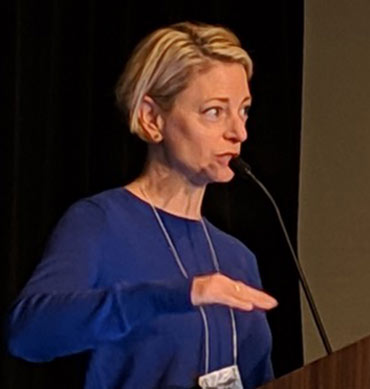

HEADS TOGETHER When two people interact, their minds may create something greater than the sum of the parts, social neuroscientist Thalia Wheatley suspects.

FG Trade/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Brains have long been star subjects for neuroscientists. But the typical “brain in a jar” experiments that focus on one subject in isolation may be missing a huge part of what makes us human — our social ties.

“There’s this assumption that we can understand how the mind works by just looking at individual minds, and not looking at them in interactions,” says social neuroscientist Thalia Wheatley of Dartmouth College. “I think that’s wrong.”

To answer some of the thorniest questions about the human brain, scientists will have to study the mind as it actually exists: steeped in social connections that involve rich interplay among family, friends and strangers, Wheatley argues. To illustrate her point, she asked the audience at a symposium in San Francisco on March 26, during the annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, how many had talked to another person that morning. Nearly everybody in the crowd of about 100 raised a hand.

Everyday social interactions may seem inconsequential. But recent work on those who have been isolated, such as elderly people and prisoners in solitary confinement, suggests otherwise: Brains deprived of social interaction stop working well (SN: 12/8/18, p. 11).

“That’s a hint that it’s not just that we like interaction,” Wheatley says. “It’s important to keep us healthy and sane.”

Wheatley and her colleagues are getting around this issue by using special cases that fit on the head and cushion motion. The team uses this technique to study brain activity in pairs of people as they make up a story together over the internet, with one subject in a scanner at Dartmouth and the other in a scanner at Harvard University. This multiperson method, called hyperscanning, may help to reveal what’s special about people working together.

When two people interact this way, “we’re creating something that doesn’t just come from me, and it doesn’t just come from you,” Wheatley says. “There’s something special about putting our minds together, about putting our heads together, to create something new that couldn’t have existed before.”

Our mind-to-mind interactions, Wheatley suspects, lead to something greater than the sum of its parts — a super-brain, an uber-mind. (She has yet to settle on the perfect term.) And her lab has been working with mathematicians on how to measure this potentially additive effect.

These sorts of interactions may become even more important for partners who spend decades together. When one partner dies, the surviving spouse’s health often declines fast. Wheatley wonders if that rapid decline might be explained by the sudden change to the partners’ shared super-mind. “It’s like you have taken this other mind as part of you,” Wheatley says. After one partner dies, “that mind is gone,” and the remaining one may be thrown off-kilter, she says.

By pushing to study brains being social, Wheatley and others hope to nudge the neuroscience field toward a more holistic view of human cognition. In keeping brain experiments too basic, scientists can “lose the meaning,” Wheatley says. “You’re missing a lot if you’re studying one person.”