THE WORM TURNS Intestinal parasites may have an upside. Researchers have discovered that people with whipworms (Trichuris trichiura, left) and mice with Heligmosomoides polygyrus (right) have fewer inflammation-provoking bacteria than they do without the worms.

AJ Cann/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0); D. Davesne/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Parasitic worms may hold the secret to soothing inflamed bowels.

In studies of mice and people, parasitic worms shifted the balance of bacteria in the intestines and calmed inflammation, researchers report online April 14 in Science. Learning how worms manipulate microbes and the immune system may help scientists devise ways to do the same without infecting people with parasites.

Previous research has indicated that worm infections can influence people’s fertility (SN Online: 11/19/15), as well as their susceptibility to other parasite infections (SN: 10/5/13, p. 17) and to allergies (SN: 1/29/11, p. 26). Inflammatory bowel diseases also are less common in parts of the world where many people are infected with parasitic worms.

P’ng Loke, a parasite immunologist at New York University School of Medicine, and colleagues explored how worms might protect against Crohn’s disease. The team studied mice with mutations in the Nod2 gene. Mutations in the human version of the gene are associated with Crohn’s in some people.

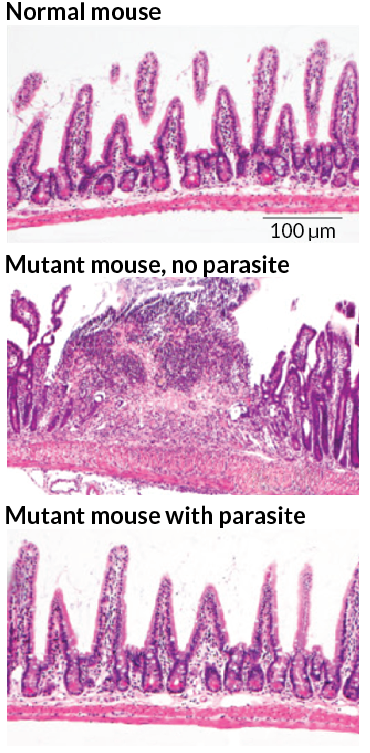

The mutant mice develop damage in their small intestines similar to that seen in some Crohn’s patients. Cells in the mice’s intestines don’t make much mucus, and more Bacteroides vulgatus bacteria grow in their intestines than in the guts of normal mice. Loke and colleagues previously discovered that having too much of that type of bacteria leads to inflammation that can damage the intestines.

In the new study, the researchers infected the mice with either a whipworm (Trichuris muris) or a corkscrew-shaped worm (Heligmosomoides polygyrus). Worm-infected mice made more mucus than uninfected mutant mice did. The parasitized mice also had less B. vulgatus and more bacteria from the Clostridiales family. Clostridiales bacteria may help protect against inflammation.

“Although we already knew that worms could alter the intestinal flora, they show that these types of changes can be very beneficial,” says Joel Weinstock, an immune parasitologist at Tufts University Medical Center in Boston.

Both the increased mucus and the shift in bacteria populations are due to what’s called the type 2 immune response, the researchers found. Worm infections trigger immune cells called T helper cells to release chemicals called interleukin-4 and interleukin-13. Those chemicals stimulate mucus production. The mucus then feeds the Clostridiales bacteria, allowing them to outcompete the Bacteroidales bacteria. It’s still unclear how the mucus encourages growth of one type of bacteria over another, Loke says.

Blocking interleukin-13 prevented the mucus production boost and the shift in bacteria mix, indicating that the worms work through the immune system. But giving interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 to uninfected mice could alter the mucus and bacterial balance without worms’ help, the researchers discovered.

Loke and colleagues also wanted to know if worms affect people’s gut microbes. So the researchers took fecal samples from people in Malaysia who were infected with parasitic worms.

After taking a deworming drug, the people had less Clostridiales and more Bacteriodales bacteria than before. That shift in bacteria was associated with a drop in the number of Trichuris trichiura whipworm eggs in the people’s feces, indicating that getting rid of worms may have negative consequences for some people.

Having data from humans is important because sometimes results in mice don’t hold up in people, says Aaron Blackwell, a human biologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “It’s nice to show that it’s consistent in humans.”

Worms probably do other things to limit inflammation as well, Weinstock says. If scientists can figure out what those things are, “studying these worms and how they do it may very well lead to the development of new drugs.”