Zombifying fungi have been infecting insects for 99 million years

Ancient amber trapped Ophiocordyceps spores bursting from a fly and an ant pupa

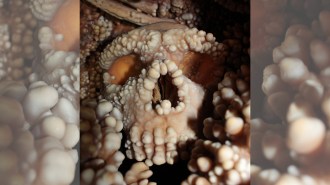

An adult worker ant carries a fungus-infected ant pupa, while a fly with a fungus bursting out of its back climbs up a tree in this artist’s reconstruction of a fossil-inspired scene from 99 million years ago.

Dinghua Yang