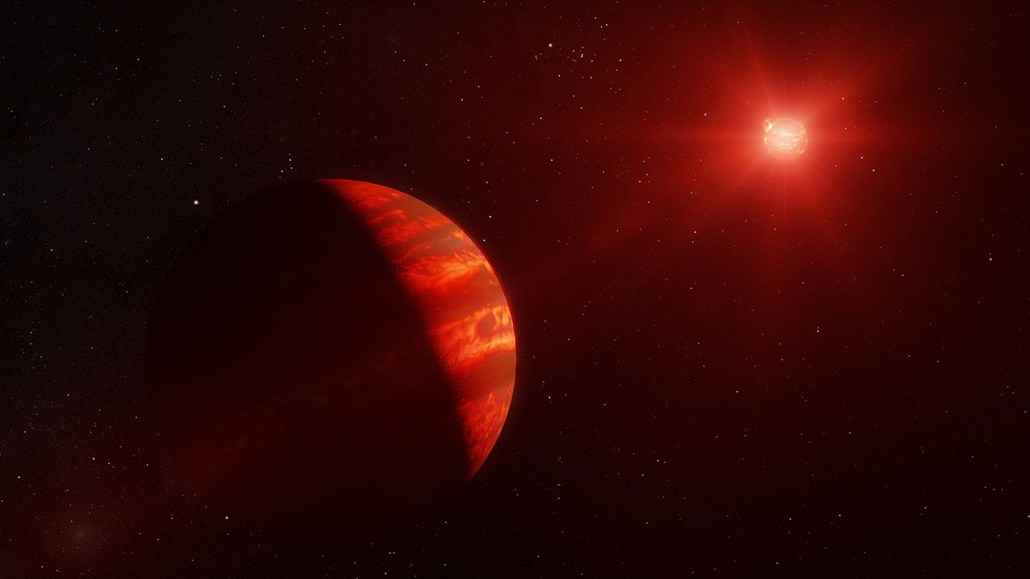

Jupiter-like planets orbiting red dwarf stars exist more often in art (shown) than in reality, according to a new study.

Melissa Weiss/CfA

If you’re looking to visit a gas giant planet in another solar system — or if you’re simply a science fiction writer who needs such a world for your story — you’d better steer clear of little red stars.

A search for planets like Jupiter around low-mass red dwarf stars came up empty, researchers report in the July Astronomical Journal. “Around 200 stars, we did not detect a single one of these planets,” says Emily Pass, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

The find — or lack thereof — lends support to a theory of giant-planet building called core accretion. In this theory, gas giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn form by gradually piecing together a solid core out of debris orbiting a young star (SN: 4/14/22). That core eventually gets massive enough to attract lots of gas. But low-mass red dwarf stars shouldn’t host much solid material to begin with, so a paucity of gas giants is in line with that theory.

About three out of every four stars in the galaxy are red dwarfs, a type of star much fainter, cooler and smaller than the sun (SN: 8/23/21). They glow dimly because they were born with little mass, about eight to 60 percent that of the sun. Previous planet searches have found that few red dwarfs have gas giant planets. But the new search targeted red dwarfs with only 10 to 30 percent of the sun’s mass, which are the most common such stars.

Pass and colleagues spent about six years searching for the Doppler shift an orbiting planet would cause in starlight as the world pulled its sun toward and away from us. All the observed stars are nearby, within 50 light-years of Earth. The closest is the well-studied Barnard’s Star, just six light-years away, which was once thought to possess two Jupiter-sized planets (SN: 4/26/69).

But no gas giants turned up around that star or any of the others. Extrapolating to the rest of the galaxy, the researchers conclude that fewer than two out of every 100 low-mass red dwarfs have planets as massive as Jupiter.

“To actually form a Jupiter [around the lowest-mass stars] is very hard,” says Edward Bryant, an astronomer at University College London, who was not one of the researchers conducting the search. “Their lack of a detection of a Jupiter analog I think is very consistent with the expectations from core accretion.” Because the disks of gas and dust around infant low-mass red dwarfs are small, there’s less material to create gas giants the size of Jupiter.

But smaller, rocky worlds stand a much better chance.

In fact, many red dwarfs do have Earth-sized planets, some at the right distances from their suns to sport pleasant temperatures. “We are talking about strange new worlds, not an Earth 2.0,” Pass says.

In our solar system, she says, Jupiter’s gravity may have prevented lots of ice from reaching Earth. As a result, our world didn’t end up completely underwater. In a planetary system lacking such a massive gas giant, an Earth-sized planet could turn into a water world that might still give rise to a highly intelligent species, but one that would live underwater — think dolphins — and not do any astronomy at all.

“It’s not saying that you can’t have life on these planets,” Pass says. “But those planets are just going to be so different than our own experiences.”