A diet full of tiny plastics triggered health problems in mice

After weeks of consuming plastics, the mice had gut and organ issues

Plastics can shed tiny particles that make their way into food, air and water. Scientists have shown that ingesting such particles can cause health issues in mice.

Australian Institute of Marine Science

ORLANDO, Fla. — Eating plastic might muck with the gut.

Mice fed tiny bits of polystyrene experienced health problems including metabolic issues and signs of organ injury, scientists reported June 1 at the annual American Society for Nutrition meeting.

The findings add to a small but growing stack of evidence that ingesting microscopic plastic particles may directly harm animals’ health, says Amy Parkhurst, a molecular physiologist at the University of California, Davis. Whether or not the findings translate to humans remains unclear.

“A lot is still unknown,” she says, but it’s possible that these plastics are one of many factors that contribute to human metabolic disease.

As plastics break down, they shed puny particles, known as micro- and nanoplastics. These plastics are ubiquitous in our environment. Parkhurst often thinks of the song “Barbie Girl,” which includes the lyrics, “Life in plastic,” she says. “I feel like we’re there and we don’t know a lot about what these plastics are doing to us.”

Scientists have found plastics in our blood, breast milk and even our brains. They’ve also linked microplastics in our arteries to enhanced risk of heart attack and stroke. Whether micro- and nanoplastics actually cause such conditions — and how exactly they may influence our health — is still kind of murky. But studies in animals offer some clues. Microplastics may trigger inflammation, reduce sperm quality and disrupt the community of microbes living in the gut, scientists have shown in mice.

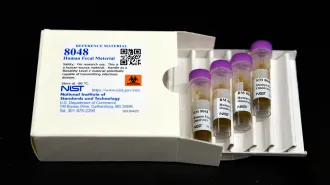

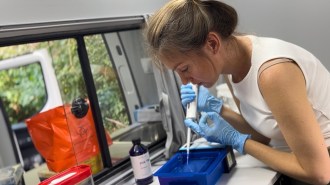

Parkhurst wanted to find out how nanoplastics might affect metabolism. She focused on polystyrene, a plastic that’s a regular in restaurants and grocery stores. It shows up in egg cartons and meat trays, utensils, straws and clear food containers. She fed mice a daily dose of polystyrene nanoparticles, which are so tiny they’re invisible to the eye. In water, they form an opaque substance that looks almost like milk, Parkhurst says.

After seven weeks of ingesting this liquid, mice displayed some distinct changes in their health, Parkhurst discovered. Their guts were more permeable, their livers revealed signs of injury and they had trouble clearing glucose, a type of sugar, from the blood. High blood sugar is a problem because it can lead to insulin resistance and other metabolic diseases like type 2 diabetes.

It’s hard to say how the nanoparticles are causing such issues. They could be physically interacting with tissues somehow, or releasing harmful chemicals into the body, says Angel Nadal, a physiologist at Miguel Hernandez University in Alicante, Spain, who was not involved with the work. Plastics can contain a cache of chemicals known to alter blood sugar regulation, including bisphenol A, phthalates and PFAS, he says.

“It is a possibility that micro- and nanoplastics are acting as vehicles for these chemicals,” he says.

It’s one of many questions that interest Parkhurst. She’d also like to find out exactly where these ingested particles wind up in the body — and what effects they could have in the long-term. Her study ran less than two months. That’s unlike the chronic exposure experienced by humans, who inhale, ingest and absorb plastic particles over a lifetime.