On a remote cluster of Indonesian islands, researchers discovered 10 new songbird species and subspecies, including this yellow-breasted Togian jungle-flycatcher (Cyornis omissus omississimus) on the Togian islands of Togean and Batudaka.

James Eaton/Birdtour Asia

It’s a veritable bevy of birds: Ten songbirds hailing from a cluster of small Indonesian islands near Sulawesi have officially joined the scientific record.

Typically, only five or six new bird species are described each year across the globe. So the discovery of five new species and five new subspecies, characterized in the Jan. 10 issue of Science, marks a remarkable expansion of bird biodiversity, considering that birds are among the most comprehensively categorized animal groups.

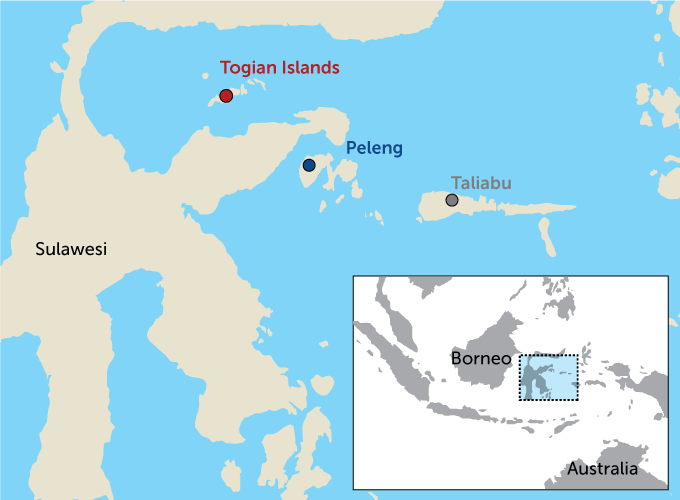

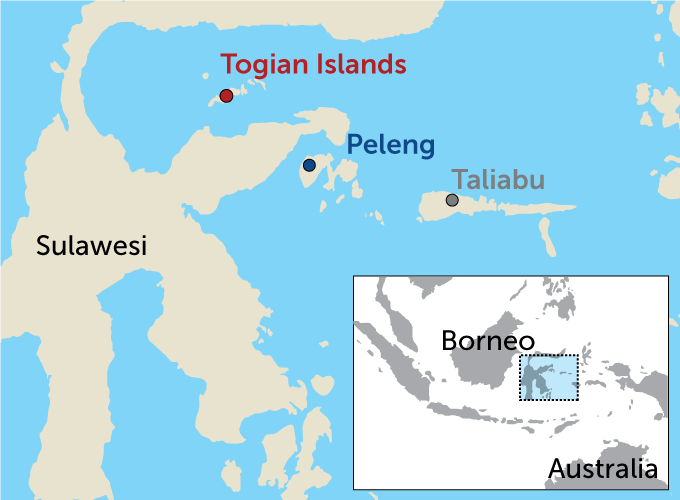

Evolutionary biologist Frank Rheindt at the National University of Singapore had an inkling these remote, forested islands with mountain highlands held an unrecognized wealth of bird life. The islands — Taliabu, Peleng and the Togian group — sit in the middle of Wallacea, a geologically and biologically complex region of Southeast Asia. But deep waters separate the islands from the nearest large landmass of Sulawesi, limiting opportunities for many animals to intermingle across the region. This includes tropical forest birds, which rarely venture out from the shady cover of the forest, let alone fly kilometers over open ocean.

In searching for new species, “it’s very important to pick deep-sea islands,” Rheindt says. “Those are the ones that are likely to have endemic species that are not shared with other landmasses.” Even more encouraging, the islands’ interior highlands hadn’t received much attention from European explorers or naturalists, who instead had focused on the coasts, he says.

Other researchers in the 1990s had reported what appeared to be distinct songbird species on the islands. But they hadn’t collected specimens, nor formally described what they’d found.

So Rheindt and his colleagues teamed up with Dewi Prawiradilaga’s group at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences in Jakarta for a 2013 expedition to investigate the islands’ bird life and collect specimens for study in the lab. Most of the birds in the study were found on Taliabu, the largest and highest of the islands.

Based on the birds’ physical features, DNA and variations in their songs, the researchers identified the five new species and five new subspecies. Some were visually striking, such as the fiery red-orange male Taliabu Myzomela honeyeater (Myzomela wahe) and the yellow-bellied Togian jungle-flycatcher (Cyornis omissus omississimus) with a cap of iridescent blue feathers on its head.

While the researchers expected to find some new wildlife on the islands, “we weren’t aware that this was going to be a bonanza of new species and subspecies,” Rheindt says.

Rheindt’s favorite? The Taliabu grasshopper-warbler (Locustella portenta), part of a group of inconspicuous brown birds with cricketlike songs that vary wildly between species. The species was particularly shy and elusive, Rheindt says, and only after multiple mountain ascents did he find one to match the songs he had been hearing. He saw immediately that it was a darker hue than the known grasshopper-warbler in the region.

“That one is the one that caught my imagination,” says Rheindt.

The cache of new birds is impressive, says Pamela Rasmussen, an ornithologist at Michigan State University in East Lansing. In recent decades, most new bird species have been found in Peru and Brazil, she says. And while it’s not necessarily surprising that there are places in Indonesia that haven’t been well surveyed, the find is “unusual in the fact that these birds have existed so long without being documented.” But more such finds aren’t so likely, she says. “There are very few places left that are likely to have so many [birds].”

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

Many of the newly described bird species and subspecies are threatened by habitat loss driven by logging and increasingly frequent and severe forest fires (SN: 10/13/11). Of particular concern is the Taliabu grasshopper-warbler, which has been squeezed into tiny vestiges of highland habitat. The species “might not survive beyond a few decades,” Rheindt says.

But conserving species requires first knowing what’s out there, so studies like these are important, he says. “Time is limited, and biodiversity is going down the drain.”