Shape-shifting molecule aids memory in fruit flies

Prionlike protein Orb2 offers clues to mechanism for remembering

FEELING FLY A protein called Orb2 may store fruit flies’ long-term memories, such as those that remind a male fly when its wing-waggling courtship is futile.

Mr.checker/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

A protein that can switch shapes and accumulate inside brain cells helps fruit flies form and retrieve memories, a new study finds.

Such shape-shifting is the hallmark move of prions — proteins that can alternate between two forms and aggregate under certain conditions. In fruit flies’ brain cells, clumps of the prionlike protein called Orb2 stores long-lasting memories, report scientists from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, Mo. Figuring out how the brain forms and calls up memories may ultimately help scientists devise ways to restore that process in people with diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

The new finding, described online November 3 in Current Biology, is “absolutely superb,” says neuroscientist Eric Kandel of Columbia University. “It fills in a lot of missing pieces.”

People possess a version of the Orb2 protein called CPEB, a commonality that suggests memory might work in a similar way in people, Kandel says. It’s not yet known whether people rely on the prion to store long-term memories. “We can’t be sure, but it’s very suggestive,” Kandel says.

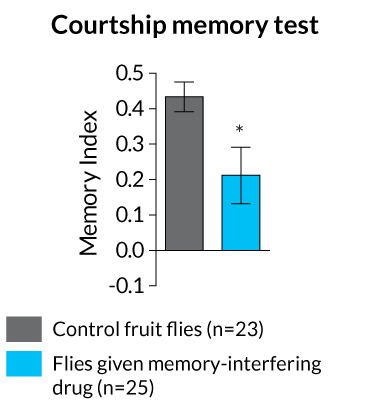

When neuroscientist Kausik Si and colleagues used a genetic trick to inactivate Orb2 protein, male flies were worse at remembering rejection. These lovesick males continued to woo a nonreceptive female long past when they should have learned that courtship was futile. In different tests, these flies also had trouble remembering that a certain odor was tied to food.

Si and colleagues found a different protein, JJJ2, that helped Orb2 switch shapes, a change that then allows Orb2 to aggregate. When the researchers boosted levels of JJJ2 protein, a situation that led to more Orb2 accumulation, flies had sharper memories. Usually, flies need about six hours of training to learn that an unreceptive female really doesn’t want to mate. But after a boost of JJJ2, flies learned that courtship was futile in only two hours. What’s more, this memory lasted for days, researchers found.

Kandel, whose work has turned up evidence for CPEB holding memories in sea slugs and mice, says that the new study makes the concept that prions can stabilize memories “quite definitive now.”

JJJ2 didn’t lead to supersmart flies that could learn everything quickly, though. The boost only came for memories that would have been formed anyway, Si says. The change “lowered the threshold for memory formation, but it has not created a situation where now all information that comes in is turned into long-term memory,” he says. “It can only [affect] memory when the conditions are right to produce a memory.”

The Orb2 results come from just long-term memory. “There could be other biochemical processes for other types of memory,” such as immune cells’ memories of former threats, Si says. Still, it’s possible that protein accumulation is one of the fundamental ways memory works.