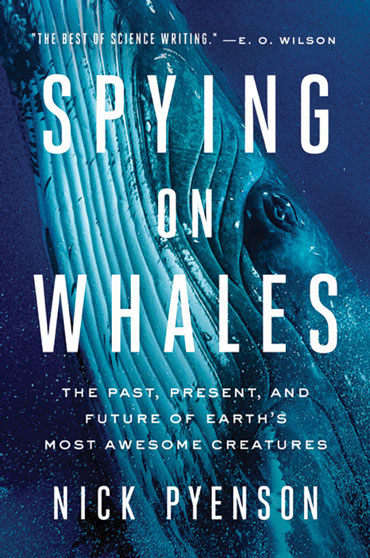

SEA GIANTS Some species of baleen whales, a group that includes southern right whales, are among the largest creatures that ever lived. Spying on Whales explores how the animals got so big and other aspects of cetacean evolution.

wildestanimal/Shutterstock

Spying on Whales

Spying on Whales