New approaches may help solve the Lyme disease diagnosis dilemma

Today’s diagnostics leave too many people in limbo

GETTING ATTACHED A tick that is attached to the skin for about two days can spread Lyme disease, the most common tickborne infection in the United States. The disease is hard to detect, but scientists are investigating new diagnostic approaches.

VOLKER STEGER/SCIENCE SOURCE

In 2005, Rachel Straub was a college student returning home from a three-week medical service mission in Central America. Soon after, she suffered a brutal case of the flu. Or so she thought.

“We were staying in orphanages,” she says of her trip to Costa Rica and Nicaragua. “There were bugs everywhere. I remember going to the bathroom and the sinks would be solid bugs.” She plucked at least half a dozen ticks off her body.

Back in Straub’s hometown of San Diego, fevers and achiness tormented her for a couple of weeks. Her doctor suspected Lyme disease, which is spread by ticks, but a test came back negative, and at the time, the infection was almost unheard of in Latin America.

For years, Straub struggled off and on with crushing fatigue and immune problems. She forged on with her studies. Dedicated to physical fitness, she started writing a book about weight training. But in late 2012, she could no longer push through her exhaustion.

“My health was shattering,” she says. By January 2013, she could hardly get out of bed and had to move back in with her parents. She describes a merry-go-round of physicians offering varying explanations: chronic fatigue syndrome, mononucleosis. She never got a definitive diagnosis, but a rheumatologist with expertise in immunology finally prescribed powerful antibiotics.

Almost immediately, Straub broke out in chills and other flulike symptoms, and her blood pressure plummeted, problems that sometimes arise when pathogens begin a massive die-off inside the body. She began to feel better, but slowly. Over the next four years, she could barely leave her house.

Stories like Straub’s are what make Lyme disease one of the most charged and controversial of all infections. It’s not hard to find tick-bitten patients who live for years with undiagnosed and unexplained symptoms that defy repeated treatment attempts.

Patient advocates point to people who agonize for years, drifting from doctor to doctor in search of relief. Battles with insurers who won’t pay for therapy without a definitive diagnosis have played out in courthouses and statehouses. Desperate patients sometimes turn to solutions that may pose their own risks. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently described people who had developed serious complications, or even died, after unproven treatments for Lyme disease.

Many, if not most, of these problems are caused by the lack of a reliable test for the infection. “This deficiency in Lyme disease diagnosis is probably the most prevalent thing that is responsible for the controversies of this disease,” says Paul Arnaboldi, an immunologist at New York Medical College in Valhalla.

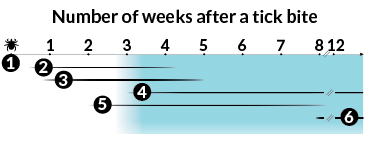

That’s why Arnaboldi and other researchers are trying to devise better diagnostics (SN: 9/16/17, p. 8). The standard two-part test that’s used now, which has changed little in concept since the 1990s, may miss about half of infected people in the early weeks of illness. The test relies on finding markers that show the immune system is actively engaged. For some people, it takes up to six weeks for those signs to reach detectable levels.

To find better ways to diagnose the disease more reliably and maybe sooner, scientists are trying to identify genetic changes that occur in the body even before the immune system rallies. Other researchers are measuring immune responses that may prove more accurate than existing tests.

The science has advanced enough, according to a review in the March 15 Clinical Infectious Diseases, that within the next few years, tests may finally be able to measure infections directly. The aim is to amplify traces of the Lyme bacteria’s genetic material in the bloodstream. Enough approaches are in various stages of research that some patient advocates have renewed optimism that the problems with testing may finally become a thing of the past.

Ticked off

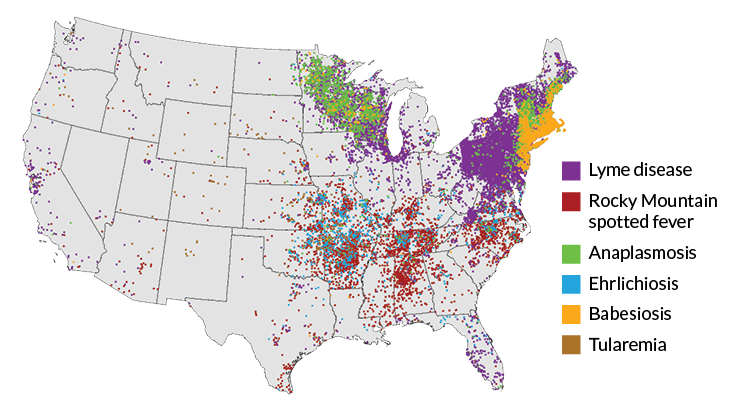

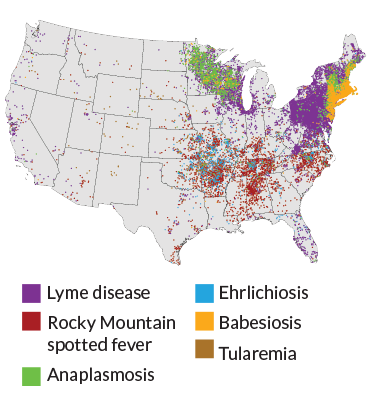

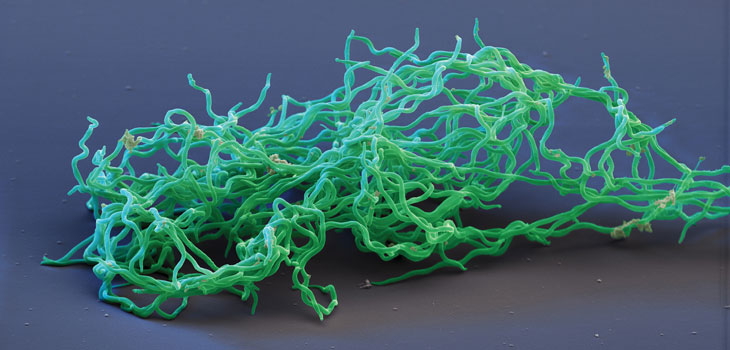

In the United States, ticks pass about a dozen illnesses to people, but Lyme disease is the most common (SN: 8/19/17, p. 16). It’s most often caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which usually hitches a ride inside black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks. When a tick bites and latches on to a person, the bacteria enter the skin, often causing a distinct, circular bull’s-eye rash radiating from the bite. But about 20 to 30 percent of infected people never experience any kind of rash, and many of those who do simply never notice it.

About 30,000 infections are reported annually in the United States, but public health experts estimate that the true number is 10 times as high.

Once in the skin, the corkscrew-shaped bacteria travel into the bloodstream and then migrate into joints and connective tissues, sometimes reaching the heart and nervous system. The problem is that treatment with antibiotics is most successful when the infection is in its earliest stages — the exact time when the standard diagnostic test is least reliable.

Doctors have an easier time diagnosing other infections using a technique called polymerase chain reaction. PCR amplifies bits of the pathogen’s genetic material from a patient’s blood, making the infection easier to confirm. But PCR isn’t sensitive enough for many Lyme infections, says Jeannine Petersen, a microbiologist at the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases in Fort Collins, Colo. Lyme-causing bacteria congregate in very low numbers in blood samples, she says, which “makes it very hard to detect the organism itself using standard methods, such as PCR.”

Indirect and ambiguous

Unable to look for the bacteria directly, at least for now, diagnosis depends on deciphering clues from the body’s immune response. The standard test has two steps. The first looks for antibodies that respond to Lyme-causing bacteria. The second, called a Western blot, validates the diagnosis by confirming the presence of other antibody proteins that are more specific for Lyme. (The two steps are used together to reduce the odds of a false-positive test.)

Because antibiotics are most effective when given early, doctors in Lyme-heavy areas commonly give antibiotics to anyone who has been exposed to ticks and has infection symptoms, such as headache, fever and muscle and joint aches. Still, not all doctors are aware that they shouldn’t wait for a positive test to begin treatment.

And sometimes doctors face dilemmas because results are ambiguous, says Charles Chiu, an infectious disease physician and microbiologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Take this scenario: By definition, a positive test for someone symptomatic for less than a month must detect at least two of three proteins for a particular type of antibody. Those proteins, and the time cutoff, were chosen during a meeting 25 years ago. “But that’s a rather arbitrary threshold,” Chiu says. He and other doctors have seen patients whose results don’t fit the criteria. Does that mean there’s no infection? Or is this patient’s immune response not typical?

In the Lyme light

Instead of waiting for antibodies to amass, Chiu wants to detect genetic changes that the body makes immediately to cope with a Lyme infection. He and his team are using machine learning, an algorithm that adapts or “learns” based on data it receives, to find the precise combination of genes that are activated when the immune system first encounters the bacteria.

“We look at all 23,000 genes that could potentially be expressed in response to a B. burgdorferi infection,” he says. “We want to narrow that to the 50 or 100 genes that are specific for patients with Lyme disease.” In theory, a computer could pick up a unique signature of genes that turn on as soon as an infection occurs and a person begins to feel ill. So far, the team has found about two dozen.

Working with partners from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, San Francisco State University and Qiagen Bioinformatics in Redwood City, Calif., Chiu’s team published data in 2016 in mBio showing panels of specific genes activated in people who have Lyme disease. Twenty-nine volunteers were tested when they were diagnosed, after three weeks of antibiotics and then six months later. During an active infection, the Lyme patients had a genetic pattern that was different than the patterns of 13 people without the disease. That Lyme signature was also different from the signatures of other infections, including viral influenza and sepsis, an immune overreaction triggered by a different organism. And the patterns changed after treatment.

As he searches for more genes in larger groups of patients, Chiu also wants to look for genetic patterns specific to the 10 to 20 percent of patients whose symptoms persist after treatment.

As many as 2 million Americans in 2020 will experience treatment failure, according to data published online in April in BMC Public Health from researchers at Brown University and the nonprofit Global Lyme Alliance in Stamford, Conn. These patients “resort to unconventional treatments and therapies. It is understandable,” Chiu says. “We need objective testing to be able to document response to therapy.”

Another problem impeding diagnosis and treatment is that ticks carry all kinds of bacteria. While Lyme is the most common tickborne infection, there are others, and they don’t all respond to the same medicine.

“In places like Long Island, up to 45 percent of adult deer ticks are infected with multiple pathogens,” says Rafal Tokarz, a microbiologist at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. To address the variability of tickborne infections and be able to treat the correct disease, Tokarz and colleagues developed a prototype test to analyze a sample of blood for eight different infections simultaneously. The approach is still based on antibodies, like the current tests, but the goal is to have a more accurate product that works sooner after infection.

The researchers described the test, which they call the tickborne disease Serochip, in February 2018 in Scientific Reports. It looks for about 170,000 total protein fragments from eight infections, including some specific for each one.

Using the test on 150 samples from patients with confirmed Lyme disease or other tick-related infections, the chip successfully picked up all confirmed Lyme cases, plus some that had been missed by conventional testing. (It also picked up other missed infections.) Tokarz’s team hopes to request approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the next two years.

Testing to a T

Like today’s standard two-part Lyme test, the Columbia-led team’s approach depends on the activity of B cells, the white blood cells that produce antibodies against Lyme bacteria. These antibodies remain in the bloodstream for months or years, even after the bacteria have disappeared. So a positive test can remain positive long after the infection is gone. When a person is still feeling sick after treatment, the test can’t tell if the old infection is hanging on, or if the person has a new Lyme infection or something else.

But the body has another type of immune response, orchestrated by T cells, which produce chemicals that recruit other cells in the immune system to fight an infection. One of these chemicals is interferon gamma. Arnaboldi, of New York Medical College, is working on a test that uses interferon gamma to detect an active Lyme infection. By not relying on antibodies, he hopes the method will distinguish an ongoing infection from one that’s already been taken care of.

“When the infection has cleared, the T cell response decreases. The cells … go quiet,” he says. Arnaboldi and collaborators have determined which particular collection of proteins from Lyme-causing bacteria are recognized by activated T cells during an ongoing infection. The researchers mix these bacterial proteins with a sample of the patient’s blood. The next day, the team checks for interferon gamma production.

If the person isn’t fighting an ongoing infection, interferon gamma levels should remain relatively stable because there are few activated T cells in the blood sample to produce the chemical. But if interferon gamma rises overnight, T cells are probably engaged and fighting.

Arnaboldi and colleagues at Gundersen Health System based in La Crosse, Wis., Biopeptides Corp. in East Setauket, N.Y., and Qiagen described tests on 29 Lyme patients before antibiotic treatment and two months after in 2016 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Interferon gamma was detected in 69 percent of patients before treatment; only 20 percent had detectable interferon gamma after treatment. In October 2018 in San Francisco, at the IDWeek research meeting, Arnaboldi and colleagues described a follow-up study: Twenty-two children with symptoms of Lyme were compared with seven children who were either healthy or had other infections. The test was more accurate in diagnosing Lyme disease than the current two-step test, with 78 percent sensitivity compared with 59 percent. In other words, the new test missed 22 percent of people who were infected — better than the 41 percent missed by the standard test.

Raymond Dattwyler, a collaborator on the study and an immunologist at New York Medical College, says that the T cell test also appears much less likely to say an uninfected person has Lyme than current tests, which can have a false-positive rate of about 25 percent, though the range varies widely. “We tested a few thousand people in Australia, where Lyme doesn’t exist,” he says, and found no false positives.

Go direct

A host of other diagnostic approaches are in testing, some using genome-sequencing technology, that may one day allow practical, direct detection of the Lyme bacteria, even with their faint presence in the bloodstream and tissues. The March review in Clinical Infectious Diseases — generated by a meeting of government, academic and industry experts at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York — noted that methods being developed could find tiny amounts of the bacterium’s signature genetic material. “The good news is the technology is there. The knowledge is there. It’s just a matter of putting them together,” says Steven Schutzer, a meeting organizer and an immunologist at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark.

While promising, new direct blood tests must demonstrate that they offer improvements over the standard test in a doctor’s office, says Petersen, of the CDC. “That’s the challenge,” she says. “You need to show the performance is equivalent or better. Tests haven’t gotten to that stage yet.”

Meanwhile, companies have introduced improvements of the old approach but with new technology. One product from Bio-Rad Laboratories in Hercules, Calif., which received FDA approval in March, detected 33 of 39 acute infections.

For patients, progress cannot come fast enough. Better diagnosis “is the No. 1 issue,” says Patricia Smith, president of the Lyme Disease Association in Jackson, N.J., a patient advocacy group. Improved tests “would go a long way to solving a lot of the problems that Lyme patients have,” she says, including an inability to get a diagnosis and treatment, difficulties with insurance reimbursement and feeling like their disease isn’t being taken seriously.

Rachel Straub knows all those challenges well. After years of cycling on and off of antibiotics, along with a host of herbal and other alternative treatments, her recovery continues. She became well enough to finish her weight training book in 2016. She returned to the gym herself a year later and resumed her graduate studies in August 2017. “I’m hoping within six to 12 months I’ll be a fully functional person,” she says, describing her health as a work in progress.

While no one can say for certain if antibiotics in the summer of 2005 would have saved Straub more than a decade of struggle, she wishes she’d had the opportunity to find out. “If you catch Lyme early, it’s simple,” she says. “If we had a better diagnostic test, people wouldn’t have to deal with all this.”