Tinnitus causes widespread trouble

Phantom sounds activate vaster expanse of brain than normal noise does, study finds

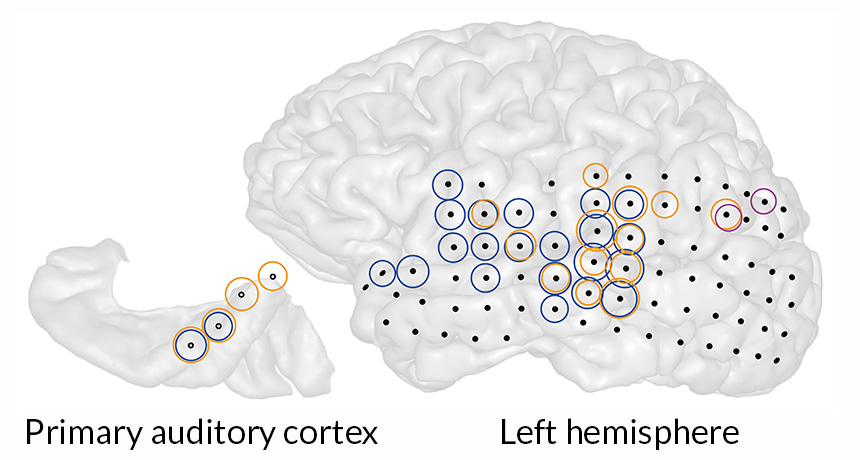

GHOSTLY RINGING A phantom noise prompted widespread changes in brain activity (circles; colors represent different frequencies of nerve cell activity) in the left side of a man’s brain, including the primary auditory cortex. The black dots represent electrodes implanted in his brain.

W. Sedley et al/Current Biology 2015