When an asteroid heads for Earth, it’s time to reconsider those doomsday plans

- More than 2 years ago

Chicken Little is right. The sky is falling.

The million-plus people living in Chelyabinsk, Russia, got that message on February 15, when a space rock some 17 meters across detonated over their homes. People rushed to the windows in wonderment as a blaze of light arced through the sky; seconds later many of them got a face full of glass shards. It was the most damaging cosmic collision since 1908, when an even bigger asteroid chunk blew up over Siberia. (In an era before YouTube and dashboard cameras, it was weeks before tales trickled out of reindeer herders being thrown from their tents by the blast.)

In a cosmic collision coincidence, most of the world’s experts on near-Earth asteroids had already prepped for February 15. Airtime was booked, suits pressed, and sound bites lined up about the threat that rogue asteroids pose to Earth. All because on that day, a 40-meter-wide space rock called 2012 DA14 was due to fly past Earth. It slipped within 17,200 miles of the surface, inside the orbits of some satellites, and departed quietly for deep space.

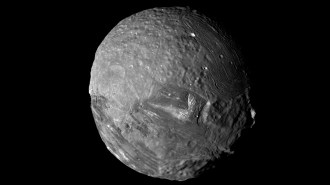

The expected asteroid flyby and the unexpected Russian blast were unrelated space rocks that happened to be zooming by, from different directions, on the same day. But they show just how unpredictable the cosmos can be. People like to talk about the huge buried scar near Merida, Mexico, created 65 million years ago by the asteroid that obliterated the dinosaurs. But a far more likely disaster will come from threats like the Chelyabinsk rock: not a planet-killer but a city-killer.

NASA has cataloged nearly 10,000 near-Earth asteroids, but that’s only a fraction of the space rocks thought to lurk out there. There may be as many as 10 million objects the size of the Chelyabinsk rock and roughly a million the size of DA14 or larger in the inner solar system. Only a small fraction of those may be pulled into Earth-crossing orbits, but when that happens you need some serious defense.

For years, a loosely knit group of astronauts, entrepreneurs and engineers has argued that countries should get their act together and scan the skies for these smaller space rocks. And for years these people have felt like Chicken Little, screaming warnings that nobody heeded. Now, just maybe, the rest of the world might.

In perhaps the biggest such effort, former astronauts Rusty Schweickart and Ed Lu head up the B612 Foundation, named after the asteroid home of Antoine St. Exupéry’s Little Prince. B612 wants to build and launch its very own space telescope, which would spot at least 90 percent of nearby asteroids that are 140 meters across or bigger and 50 percent of 30-meter-wide passersby.

Other asteroid search groups have popped up recently, many of them interested in space rocks less for their threat and more for the riches they could yield. Mining asteroids for metals and raw materials for fuel could reduce the amount of stuff that future space missions would have to carry. One company wants to deploy sentry lines of 70-pound spacecraft, dubbed FireFlies, in rings around Earth as a first step in locating mining targets. Another group wants to send smaller telescopes into space to test technologies for future asteroid mining.

Canada has already taken an early, crucial step. On February 25 it launched its Near-Earth Object Surveillance Satellite, the first orbiting probe designed specifically to hunt asteroids. It will focus on rocks coming from near the sun, which ground-based observatories can’t detect.

But once you find an asteroid threatening Earth, what do you do about it? You might have a year’s lead time, or a month, or maybe only a few hours. Then it’s time to bring in the Armageddon-style weapons.

Some scientists think humankind should blast the incoming rock with lasers, vaporizing its surface. Others want to park a “gravity tractor,” in the form of a spacecraft, close enough to the asteroid to provide a tiny gravitational tug. In either scenario, just a small deflection in the asteroid’s path would be enough to nudge it safely aside and avoid a collision with Earth.

NASA and the European Space Agency are even working on a tandem mission to beat up on incoming asteroids. A planned test run calls for two spacecraft to fly to a pair of asteroids. Then one craft would smash into one of the rocks, while the other probe studies how the collision affects the asteroids’ trajectory.

If the asteroid hunters have their way, we’ll soon know not only all the rocks that are headed toward Earth, but also what we might do the next time one gets close. Bruce Willis isn’t always going to be around to save us, so planning for a sky that’s falling might just be a good idea.

SN Prime | March 4, 2013 | Vol. 3, No. 9