mRNA vaccines hold promise for many diseases. Now the tech is under fire

U.S. officials cite safety and efficacy concerns. Scientists say that's factually incorrect

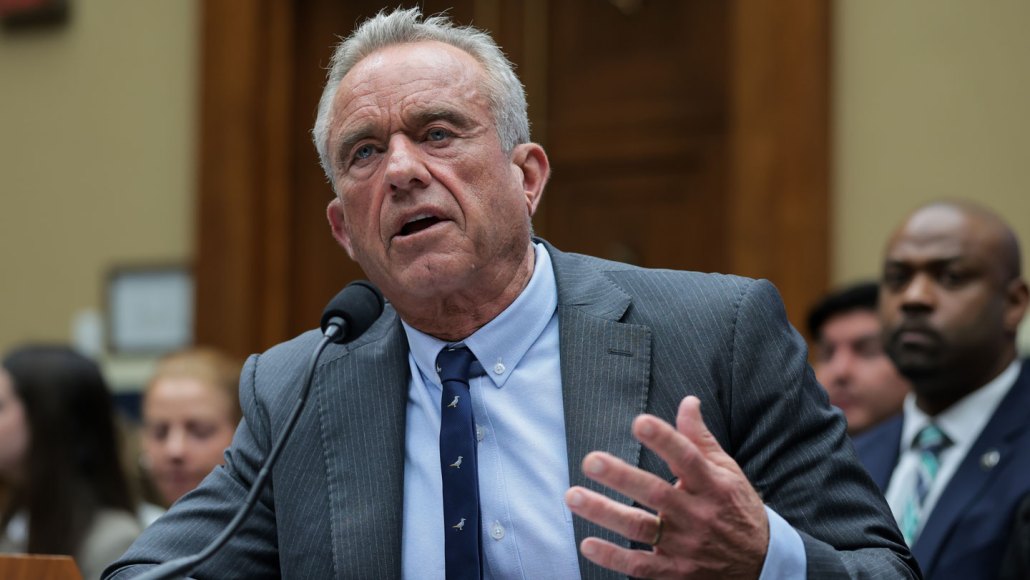

HHS secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s announcement that the U.S. government will wind down nearly two dozen projects involving mRNA vaccine research for infectious diseases could have big repercussions for related fields, experts warn.

Kayla Bartkowski/Staff/Getty Images

The United States may be losing its edge in mRNA technology.

The technology, which powered life-saving COVID-19 vaccines and is now rocketing new cancer therapeutics forward, will soon undergo a scientific slowdown. On August 5, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced it would wind down mRNA vaccine development under the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA.

HHS’ plan to terminate 22 contracts, largely related to infectious diseases, have stoked uncertainty and dismay across academia and industry. Experts warn this move could hobble the country’s preparedness for future pandemics. It might also set off an avalanche of consequences for other scientific and medical fields, including research on mRNA vaccines for treating cancer, autoimmune diseases, allergies and even HIV.

This is work that “will improve human lives,” says Elias Sayour, a pediatric oncologist at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville. “If mRNA were to fulfill its promise, you’re talking about treatments, cures and therapies that improve outcomes across the life-span and across a number of diseases.” Slowing down the pace of today’s research stymies progress on tomorrow’s cures, he says.

That’s no exaggeration, says Jeff Coller, an mRNA biology researcher at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Messenger RNA, or mRNA, technology has brought scientists closer than people think to curing diseases that have long defied treatment, he says. Take pancreatic cancer, for which a promising mRNA vaccine is currently in the works. And cystic fibrosis, a disease that now has a handful of mRNA-based treatments in development. And just this year, scientists reported a personalized mRNA medicine used to treat baby KJ, an infant with a rare and life-threatening genetic disorder.

“The mRNA-based drugs that are coming out are lifesaving,” Coller says. He thinks termination of these projects will have a chilling effect on anyone looking to develop mRNA-based therapeutics. HHS’ announcement “was literally a shot across the bow,” he says. “It’s a clear message to the entire industry that the United States is no longer going to support mRNA-based research and development.”

HHS claims about mRNA vaccines aren’t based in science

While HHS seems to be ending a range of research projects involving mRNA vaccines, details of the decision and the rationale behind it remain murky.

A handful of those 22 projects focused on alternate ways to administer these vaccines, such as inhaling a powdered form or using a microneedle patch. Others seem to have already ended or don’t involve mRNA at all.

The biotech company Moderna, for instance, said in a statement to CNN that it didn’t actually have any projects ongoing with BARDA. HHS ended funding for Moderna’s pandemic flu mRNA vaccine in May. And Tiba Biotech, an RNA-medicines startup listed among the terminated contracts, said that it was surprised to hear the news. “The Tiba project does not involve the development of an mRNA product,” the company said in an emailed statement.

HHS did not name all the programs winding down and, when asked, did not provide the full list to Science News, nor any new explanation for the decision. But HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and National Institutes of Health head Jay Bhattacharya have offered some — seemingly conflicting — reasons for the cuts. In the HHS announcement, Kennedy claimed that mRNA vaccines were ineffective against COVID-19 and suggested that other vaccine platforms would be safer and more adaptable.

“All of this is just factually incorrect,” Coller says.

For example, in a video announcement posted to YouTube, Kennedy said that a single mutation in a virus can make an mRNA vaccine ineffective. But while one mutation may indeed make these vaccines less effective, that can be true of any vaccine platform, not just mRNA-based ones, says an NIH-funded immunologist who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation.

Kennedy seems to have it backward, the immunologist says. Vaccines based on mRNA actually make it easier for scientists to adapt to mutating viruses.

Infectious diseases physician Onyema Ogbuagu agrees. These vaccines are especially nimble, says Ogbuagu, of Yale School of Medicine. They’re based on mRNA, a messenger molecule that occurs naturally in the body. It tells cells how to make specific proteins. Medicines like the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines direct the body to build a viral protein fragment, training the immune system to recognize and target the virus during infection. If a virus mutates, scientists can simply swap in a new stretch of mRNA into the vaccine’s backbone, like snapping a new brick into a Lego car.

This strategy helped save millions of lives worldwide. From 2020 to 2024, COVID-19 vaccinations averted some 2.5 million deaths, scientists estimated in JAMA Health Forum in July. Other estimates put that number at more than 14 million.

“We’re in a position where we’re trying to defend something that literally should speak for itself.”

Onyema Ogbuagu

Yale School of Medicine

For Ogbuagu, who led clinical trials for mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, HHS’ announcement was devastating. These vaccines changed the trajectory of a lethal pandemic, he says. “They really came to the rescue.” But instead of being celebrated, the technology is steeped in suspicion and distrust.

Such distrust is why the mRNA vaccine platform “is no longer viable,” Bhattacharya said in an August podcast interview with Steve Bannon, chief White House strategist during Donald Trump’s first presidency. But some of that distrust has been fueled by Kennedy himself, by misrepresenting mRNA vaccines’ safety and efficacy, the anonymous immunologist says. It’s a bizarre feedback loop, where one government official casts doubt on the technology, and another cites that doubt as the reason the technology won’t be successful. “It’s like they’re fulfilling their own prophecy.”

Ogbuagu calls the whole situation disheartening. “We’re in a position where we’re trying to defend something that literally should speak for itself.”

mRNA vaccines are a bright light in therapeutics

Scientists have been building mRNA vaccine technology for decades, but the pandemic catapulted it into mainstream medicine.

Under Trump’s first administration, a program called Operation Warp Speed brought scientists in government and industry together to speed development of COVID-19 vaccines. Just nine months after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, scientists got the job done. On December 11, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use. A week later, authorization for Moderna’s mRNA vaccine followed.

“This was an unbelievable advance,” says Elizabeth Jaffee, an oncologist who works on cancer vaccines at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Operation Warp Speed trailblazed the technology, ultimately helping to make mRNA vaccines relatively easy to produce, transport and deliver.

These are the same qualities scientists need in cancer vaccines, Jaffee says. In fact, work on mRNA COVID vaccines propelled cancer research forward, she says, because scientists now had a safe and reliable platform for creating cancer-fighting vaccines.

Globally, scientists have kicked off more than 120 clinical trials for RNA-based vaccines targeting various cancers, including those of the brain, breast, skin and pancreas. These trials include vaccines that rely on mRNA, along with vaccines based on other types of RNA. Furthest along may be a personalized melanoma mRNA vaccine in development at Moderna and the pharmaceutical company Merck. The vaccine, tailored to an individual patient’s tumor, tells immune cells exactly what to target. In a trial of 157 patients, combining the vaccine with the popular immunotherapy drug Keytruda cut patients’ risk of cancer recurrence or death nearly in half over three years, compared with using the drug alone, scientists reported in 2024.

And the biotech companies BioNTech and Genentech have seen “unbelievably promising data” for their mRNA vaccine for pancreatic cancer, Sayour says. In a small clinical trial, this vaccine kept some patients cancer-free for over three years, scientists reported earlier this year. That’s a big deal because pancreatic cancer is “one of the hardest tumors in the world to treat,” Sayour says.

Sayour’s lab hopes to create a universal cancer vaccine that ignites patients’ immune response in a way that fends off many types of cancers. His team has recently taken a step toward that goal, with an experimental mRNA vaccine that boosted the anticancer effects of immunotherapy drugs in mice, Sayour and his colleagues reported July 18 in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Sayour considers mRNA technology “the brightest light in the therapeutic space.” And he points out that mRNA-based medicines aren’t just for cancer, with potential applications in other challenging diseases.

In fact, several early-stage mRNA vaccines suggest the technology might one day protect people from HIV. In experiments in animals and people, the mRNA vaccines targeted a portion of the virus that may make it vulnerable to antibody attack, scientists reported in two papers published July 30 in Science Translational Medicine.

Such progress in infectious diseases and other fields is what makes the mRNA vaccine platform so promising, Ogbuagu says. It’s “really advancing the field of disease prevention in remarkable ways.”

The future of mRNA research in the United States

The rapid pace of U.S. mRNA technology progress is not guaranteed to continue — nor is government support of mRNA-based therapies.

Kennedy’s announcement mentioned terminating 22 projects worth nearly $500 million, which is a drop in the bucket of HHS’ proposed $95 billion budget for fiscal year 2026. But “it’s not about the money,” Coller says. Instead, it signals to the world — and to drug companies — that the United States is not going to be leading in this area of science.

Think about a company investing millions of dollars into an mRNA-based medicine, he says. “Can you be absolutely confident that your product is going to make it to the FDA and be approved?”

Those concerns are what Coller has been hearing from academic and biotech leaders in the field. He founded a nonprofit organization called the Alliance for mRNA Medicines, which recently surveyed its members about how policies targeting mRNA vaccines might influence their business. “The overwhelming response from the industry is that this would dramatically change their consideration of developing new mRNA-based therapeutics within the United States,” he says.

But that doesn’t mean advancements in this area will screech to a halt. Instead, Coller fears, countries like China could take the lead, leaving the United States behind.

Though the HHS cuts target infectious diseases research, Sayour emphasizes that the mRNA research community is interconnected. Discoveries in one field can spur discoveries in others, he says, so losing support in one area is a blow to all.

The NIH funds researchers like Sayour and others working on mRNA cancer vaccines, like the pancreatic cancer vaccine currently advancing through clinical trials. Though HHS has not said it plans to stop supporting mRNA cancer research, it’s something that worries Sayour and others in the field. “Of course I’m concerned,” he says.

As a society, we stand to lose a ripe opportunity to address some of our most recalcitrant medical problems, he says. That’s because mRNA therapies “can be customized in an infinite number of ways” for conditions across the spectrum of human health, like cancer, autoimmune disease, infectious disease and neurodegenerative disorders.

But despite the latest cuts, Sayour remains optimistic about the future of mRNA vaccines in the United States. “I think we’re at a crossroads,” he says. “I have to believe that as a country, we will do the right thing.”