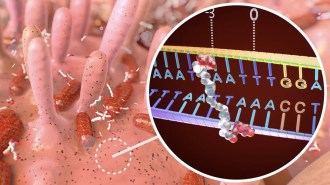

Insect larvae like these can colonize dead bodies and offer clues about time of death. A new machine learning technique can identify species based on chemical fingerprints of insects’ puparial casings.

Paige B. Jarreau/ LSU

Crime scene clues from blowflies may help reveal a victim’s time of death — and other murderous details — perhaps even years later.

When colonizing a dead body, these insects lay eggs that mature into adult flies, leaving behind telltale remnants. The remnants, called puparial casings, could help investigators back calculate when someone died, based in part on the time it takes for insects to reach the casing stage.

But different species mature at different rates. To accurately estimate time of death, figuring out which species you’re dealing with is crucial, says Rabi Musah, an organic chemist at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge.

Now, her team has developed a rapid method to do just that. By combining an AI tool with chemical detection, researchers can identify fly species from their casings — all within about 90 seconds, Musah’s team reports October 1 in Forensic Chemistry.

Time of death isn’t the only thing these casings could help determine, says Falko Drijfhout, an analytical chemist at Keele University in England who was not involved with the work. They could also offer other clues about a crime, like whether a body has been moved. “Casings will remain with the corpse,” he says. If investigators find casings from a species that lives far away, that’s a sign the body has been relocated.

Blowflies are death-detecting wizards. They can spot a dead body within minutes and from up to two kilometers away. These insects lay eggs on the body, which serves as a food source for the maggots that later hatch. As the maggots mature, their bodies transform into pupae, which are housed by puparial casings — “sturdy, hardy little structures,” Musah says. The adult fly ultimately emerges from these casings.

Eggs, maggots, pupae and casings can all offer information about a death’s timing — if you can identify the species. That’s not always easy to do, because at these early stages, different species tend to look alike. One way to tell them apart is to capture eggs or maggots from the body and then rear them to adulthood, when it’s easier to identify individual species. But that doesn’t work if you’ve only got casings, Musah says. Another way to differentiate species is by DNA analysis. But that can be tricky if insect material has been exposed to the elements and DNA has degraded.

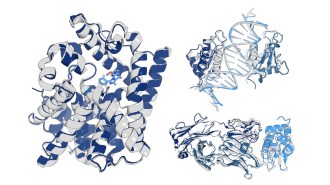

Musah’s team came up with a simpler solution. The researchers mapped insect casings’ chemical fingerprints, which are unique to each species, using a technique called field desorption-mass spectrometry. Then, the team used a machine learning prediction model, a type of artificial intelligence, to crunch that chemical data and churn out the species identity.

The researchers’ mass spectrometry technique let them tap into compounds not typically captured by other chemical detection methods, Drijfhout says. That gave the team more data to work with, which is helpful for species identification.

Musah and her colleagues had trained their model on chemical fingerprints of hundreds of casings, sourced from lab-raised blowflies. Then, the team tested the system on 19 other casings that it had never seen before and had been collected across the country. The AI model identified the blowfly species the casings belonged to correctly each time, Musah’s team reported.

The researchers also showed that their chemical detection technique could pick up chemicals that tend to stick around for years. If scientists could map how these molecules weather over time, that could one day offer a new tool for estimating time of death from puparial casings, long after a death has occurred. That would let you say, “these remains have likely been here 15 years as opposed to two years,” Musah says.

The molecules Musah’s team detects can carry clues about crimes, like time and location of death and perhaps even cause — casings can contain poisons ingested by victims. These molecules are like a language, she says. “If you’re listening, there’s all this information you can extract.”