Atom & Cosmos

Oxygen molecules in space, Earth’s second moon, a mission to Jupiter and more in this week’s news

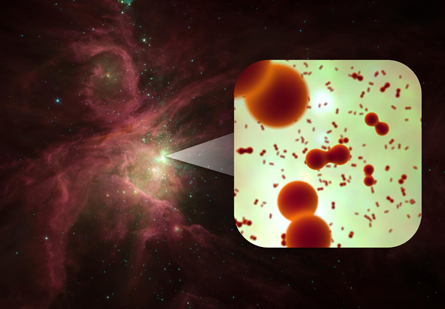

Interstellar oxygen bar

There’s no breathing in space, but there is oxygen. Astronomers have long known that single oxygen atoms float in interstellar space, but now scientists have also spotted molecules of two linked oxygens. The European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory found the molecules in a star-forming region in the constellation Orion; researchers aren’t sure why molecular oxygen has been so elusive until now. Paul Goldsmith of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. and his colleagues describe the find in an upcoming Astrophysical Journal. —Alexandra Witze

Earth’s antiprotons

Batten down the hatches: Astronomers have found a belt of antiprotons, the antimatter counterparts of protons, around the planet. Theorists have long predicted the existence of such a belt, created as antineutrons escape from the atmosphere and decay into antiprotons. Now, the Italian-led PAMELA instrument has looked down from space and measured up to three times more antiprotons than expected over the South Atlantic Ocean — the most antiprotons ever found near Earth. A team led by Alessandro Bruno of the University of Bari in Italy reports the discovery in the Aug. 20 Astrophysical Journal Letters. —Alexandra Witze

Solar explosions just whirls

What look like small explosions in the sun’s atmosphere might actually just be twirling jets of superhot gas. In these explosive events gas molecules appear to suddenly triple their speed, zooming toward or away from peering astronomers at 150 kilometers per second or more. A German and American team reports online July 26 in Astronomy and Astrophysics that what look like explosive gas outbursts are actually spinning helical jets. The speedy readings come from molecules in the gas tornado moving backward and forward from the observers’ perspective. —Camille M. Carlisle

Earth’s extra moon

For millions of years, Earth’s moon may have had a small companion – a co-orbiting moonlet one-third its diameter. Then one day, they gently collided. But instead of forming an impact crater, the little moon splattered across the bigger moon, depositing its rocky remains on the lunar farside. Scientists from the University of California, Santa Cruz think this pile of wreckage could explain puzzling geological differences between the lunar hemispheres: The near side is flat, low and rich in rare earth elements, while the far side is higher in elevation, cratered and sprinkled with mountains. The team describes the meeting of the moons in the Aug. 4 Nature. —Nadia Drake

Juno to head for Jupiter

NASA’s solar-powered spacecraft Juno blasted off from Kennedy Space Center on August 5. Juno rode an Atlas V rocket into space, and will fly for five years before reaching Jupiter. Once there, the spinning, synthetic moon will circle the gassy, spotted giant 32 times, peering beneath Jupiter’s cloudy surface to determine composition and water content, studying the planet’s intense magnetic field — likely produced by an internal sea of liquid, metallic hydrogen — and hopefully snapping some sweet photos of Jupiter’s auroras. At the end of the year-long mission, Juno will exit with flair — by launching itself into the planet. —Nadia Drake