From the August 11, 1934, issue

RUINS OF SARGON’S PALACE YIELD NEW MAGNIFICENCES

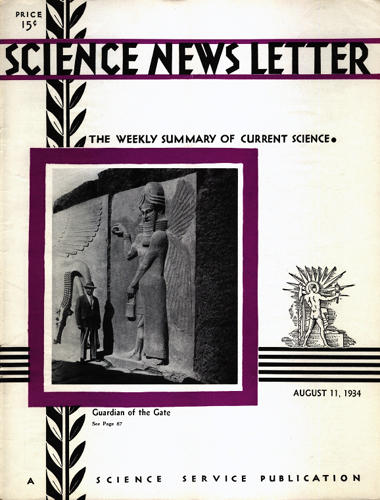

Mermaids, unicorns, sphinxes, and the strange winged “genii” typical of Assyrian sculptural art have been dug up by archaeologists of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, working under Dr. Henry Frankfort, in the ruins of Khorsabad in Mesopotamia.

Khorsabad was the capital of King Sargon of Assyria, who reigned early in the 8th century B.C. For some reason he was dissatisfied with Nineveh, the ancient capital of his nation, and decided to build a new royal city for himself. His venture in city-building, however, was not permanent; after his death, his successor returned to Nineveh, and Khorsabad’s magnificent palaces and temples were left to crumble and be drifted over by centuries of desert dust, undisturbed until the spades of the Oriental Institute’s workmen broke through.

Outstanding among the new finds are four great carved panels that guarded the palace entrance. Two of these bear representations of the human-faced winged bulls, the guardian genii of Assyrian sacred and official places. The other two show winged genii in human form, wearing horned turbans to show their supernatural character. These appear to be sprinkling the bulls with sacred water from small pails that they carry in their left hands. All four of the figures are of heroic size, approximately 3 times as tall as a man.

WOOD-EATING TERMITES MUST HAVE FUNGI ON FOOD

Termites, destructive feeders on all wooden things, apparently need a dressing of fungi on their stiff diet, just as human gourmets require a certain mouldiness on cheese.

This point was brought out by Dr. Esther C. Hendee of the University of California, who discussed her termite researches before the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Dr. Hendee put similar batches of termites on three kinds of diet: well-rotted wood thoroughly riddled with fungi, new wood with a recent development of fungus growth, and new wood with no fungus at all. The insects throve best on the well-rotted wood, next best on the wood with fresh fungus growth.

On the fungus-free wood they did not do well at all. They lost weight and did not regain it. They were sluggish and inactive, and abnormal in appearance. They resorted to cannibalism to an excessive degree.

Dr. Hendee has therefore concluded that termites of the species she studied require fungus on the wood, as well as one-celled animals in their own digestive tracts, for the proper handling of their tough provender.

HOMO SAPIENS MAY BE 10 MILLION YEARS OLD

Homo sapiens, or man as we know him, has lived longer on the face of the Earth than science has hitherto supposed. He rose from among the other primates toward the geologic age known as Miocene. This makes him some 10 million years old.

Discussion on man’s place among the primates presented to the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences in London indicates that scientific opinion based on new facts and researches tends to the acceptance of these ideas.

The Oxford anatomist Prof. W. Le Gros Clark emphasized the paramount importance of American research on the anatomy of the foot and explained that Dr. Dudley J. Morton of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, finds in the structure of the foot the strong suggestion that the human stock diverged from the anthropoid line of evolution when the common ancestors of man and other primates were little larger than the modern gibbon, a relatively small animal to be seen in most zoological gardens and belonging to the same Simiidae family as the chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan.