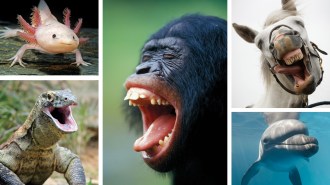

A greater noctule bat is caught in a mist net with a passerine feather and blood in its mouth.

Jorge Sereno

Vampire bats are a Halloween staple, and now they’ve got company. Another bat species snatches birds out of the air for a gruesome midnight feast.

Songbird DNA has previously shown up in the guano of three bat species, so researchers knew these flying mammals were eating more than just insects. But how, exactly, does a bat hunt a bird? It turns out that Europe’s largest bat, the greater noctule, is a formidable aerial hunter that captures, dismembers and consumes migrating songbirds for the ultimate in-flight meal, researchers report in the Oct. 9 Science.

For years, scientists have tried to understand how these bats capture prey, but it’s challenging to know what animals are doing high in the night sky. The solution: Track their movements, says bioacoustician Ilias Foskolos of Denmark’s Aarhus University. He and his colleagues equipped greater noctules (Nyctalus lasiopterus) with biologgers. These devices feature multiple sensors, including accelerometers to record 3-D movement, magnetometers to log direction, altimeters to measure altitude and microphones.

“Using [these] high-tech approaches, the Science paper is the first to track the hunting maneuver of a greater noctule chasing and catching a robin,” says Danilo Russo, a bat ecologist at the University of Naples Federico II in Italy who was not involved with the study. “Although there is no visual observation of the hunting episode, in my opinion, this study nevertheless provides compelling evidence that birds are caught in flight.”

None of the sensors recorded video of the bats’ movements or meals, but they did track each bat’s nightly activities, giving researchers a peek into their mysterious hunting behaviors. Listening to the recordings “is like flying with the bats,” says Elena Tena, a bat conservationist at Doñana Biological Station in Seville, Spain, where the team captured and tagged bats for the study. “You can listen to the flapping” of their wings and the calls of frogs as the bats wing their way across Doñana’s marshes, she says.

Microphones also captured feeding buzzes as the bats approached their prey. These buzzes, followed by chewing sounds, indicated a successful hunt, Tena says. Most of the 611 hunting events involved insects near the ground, but two stood out. In both cases, the bats flew to high altitudes — above the height of migrating songbirds, more than 1,200 meters up. The predators then homed in on a bird and approached with loud feeding buzzes.

“Because the frequencies are so high, the birds … can’t hear them,” Foskolos says. Both birds responded at the last moment, probably reacting to the bat’s touch or the sound of its wings. “They probably do dives and spirals and complicated maneuvers,” to evade the bats, he says. “They seem to go vertically down, because that’s what we see from the data.”

One bird escaped near the ground. The other wasn’t so lucky. The microphones captured its distress calls followed by a 23-minute in-flight meal. “The bat was flying normally because of the accelerometer data, and chewing and echolocating at the same time,” Tena says. “Sometimes you could hear that it must be biting bone.”

Removing wings seems to be part of their process. “Sometimes, when we were capturing [bats], suddenly, some wings [would] fall to the ground,” Tena says. DNA analysis of wounds on the wings confirmed the bite of a greater noctule bat. And netted bats of the same species have occasionally been caught with red-stained lips and feathers hanging from their mouths.

Though the team now has evidence showing how these bats prey on songbirds, “we still know very little about this species,” Tena says. This study is a leap forward in understanding the greater noctule’s role as one of Europe’s top predators.