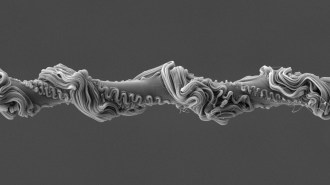

Bedbugs (one shown on human skin) may be among the first pests to truly exploit and thrive in the urban environment, increasing sharply in population during the dawn of the first cities.

Benoit Guenard

The earliest cities may have had plenty of parasitic, six-legged tenants.

Common bedbugs (Cimex lectularius) experienced a dramatic jump in population size around the time humans congregated in the first cities. The wee bloodsuckers were probably the first insect pests to flourish in a city environment and possibly one of the first urban pests overall, researchers report May 28 in Biology Letters.

Originally, bedbugs fed on bats. But around 245,000 years ago, one lineage took up a human diet (probably starting with Neandertals) and never looked back. About a decade ago, urban entomologist Warren Booth of Virginia Tech in Blacksburg and his colleagues extracted and analyzed the genomes of bedbugs from both lineages to aid future research on the insects’ evolutionary history. The team was interested in how organisms adapt to urban life, and bedbugs, as widespread indoor insects today, were a good example to study.

About a year ago, when Lindsay Miles — also at Virginia Tech — analyzed the genetic data to estimate past changes in bedbug population size, there were some surprises, Booth says. The team expected to see population drops about 19,000 years ago around the end of the last expansion of Ice Age glaciers due to environmental changes like habitat loss. While both lineages declined, the human lineage took a sharp upswing around 13,000 years ago, plateaued and then spiked again 7,000 years ago. In contrast, the bat lineage is still declining.

“Something different happened with human-associated bedbugs that caused that increase,” Booth says.

The timing of this dramatic pivot from dwindling to thriving aligns with the emergence of the earliest known cities in western Asia and their subsequent expansions over the following millennia. Before, humans were mostly nomadic and didn’t intermingle with other groups of humans as regularly as people do today. So the bedbugs didn’t mix and mingle either. But when humans began gathering in cities, it was a whole new world for the bedbugs along for the ride. The team proposes that the bugs interbred, exploded in numbers and adapted to the fledgling urban ecosystem.

The team thinks bedbugs were one of the first pests — species harmful to humans physically or economically — to mold themselves to city life and were probably the first urban insect pest.

“House mice have been associated with humans for probably about 15,000 years,” Booth says. “But they do just fine without us as well, whereas human-associated bedbugs are truly reliant on humans.” Other species became closely tied to cities but did so much more recently. German cockroaches appear to have evolutionarily rooted themselves to human settlements just 2,100 years ago, and black rats about 5,000 years ago.

Mark Ravinet, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oslo who was not involved with the study, says that the findings show how bedbugs can help researchers better understand how species evolve to live with us. “That is really important for helping us understand how rapidly species can adapt to human environments and what sort of adaptations are necessary to do so.”

Ravinet is interested in seeing genomic comparisons of bedbugs across the globe. “I would imagine that human-associated bedbugs likely arose in different places around the same time.”