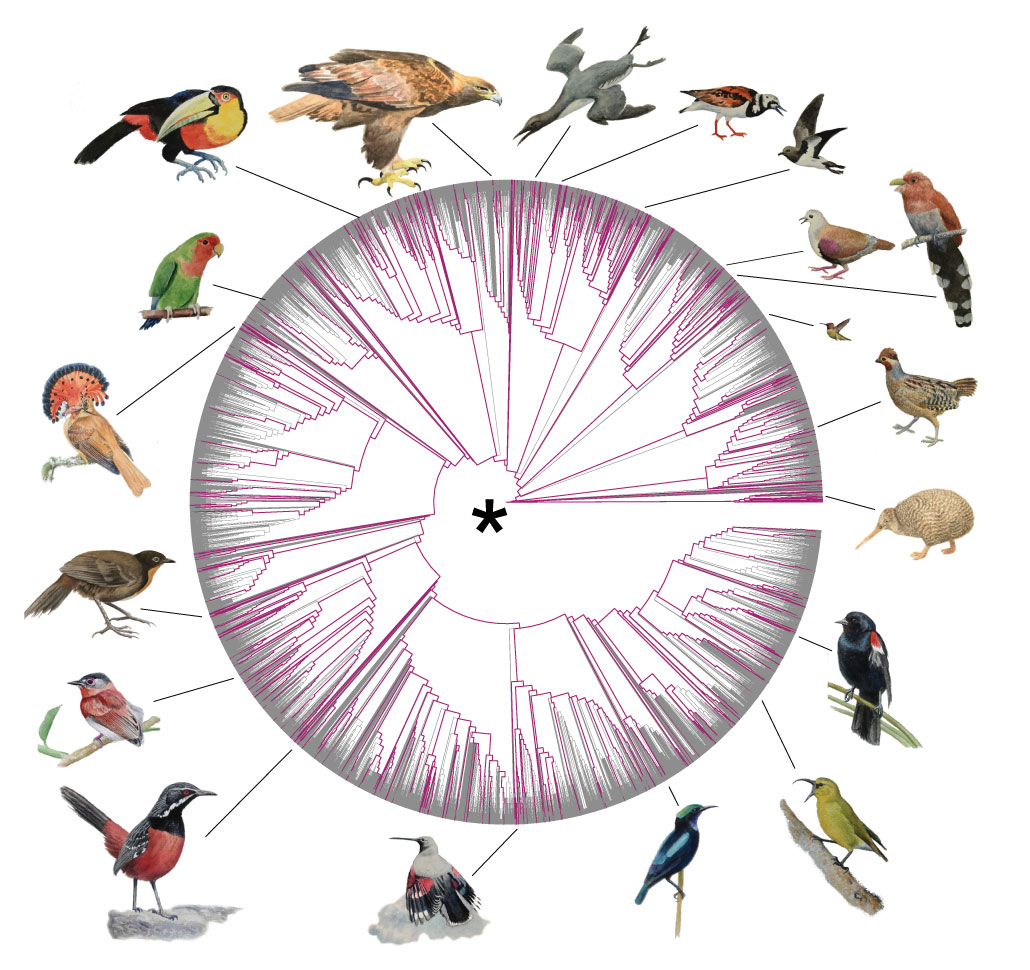

Hundreds of new genomes help fill the bird ‘tree of life’

Avian genetic toolkits could let scientists unravel 150 million years of evolutionary history

A greater roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus) catches a scaly snack. The bird is one of the animals whose genetic instruction book, or genome, has been assembled for the first time.

Brian Schmidt/Smithsonian

From gulls to grouse to grackles, more than 10,000 bird species live on this planet. Now, scientists are one step closer to understanding the evolution of all of this feathered diversity.

An international team of researchers has released the genetic instruction books of 363 species of birds, including 267 genomes assembled for the first time. Comparing all of that genetic data can help scientists figure out how the varied traits of birds — from their diverse, spellbinding songs and courtship displays to their adaptations for flight — have evolved, the team says in the Nov. 12 Nature.

Birds have long received scientific attention, says ornithologist Michael Braun of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., one of the researchers involved in the project. “That’s partly because birds are relatively easy to see out in nature,” he says.

To compile some of the newly assembled genomes, the team took DNA from bird tissue samples in 17 scientific collections from around the world. Overall, the data cover roughly 92 percent of all modern bird families. Some species, such as chickens, are familiar; others are rare, such as the Henderson crake (Zapornia atra), found only on remote Henderson Island in the South Pacific.

Scientists are just starting to uncover the secrets of avian evolution hidden in the genomes. Braun says that the data can be used better understand everything from the parallel evolution of flightlessness in ratites like emus and kiwis (SN: 4/4/19) to the evolution of vision and song learning in birds overall.

Already, the researchers have found peculiarities in the genomes of passerines — the order of songbirds that includes over half of all modern bird species, though the origin of this diversity is poorly understood. These alterations include the loss of a gene involved in the development of the vocal tract, possibly influencing passerines’ songs.

This new information is the latest from the Bird 10,000 Genomes Project, but it won’t be the last. The international research collaboration doesn’t plan to stop assembling and releasing avian genomes until every last bird species on the planet is included.