A breakdown product, not ketamine, may ease depression

Hallucinogenic drug’s metabolite shows rapid effectiveness without side effects in mice

BREAKDOWN The anesthetic drug ketamine can ease depression, small studies have shown. But the benefit may come not from ketamine itself, but from one of its breakdown products, a new study suggests.

Psychonaught/Wikimedia Commons

Ketamine, a drug that has shown promise in quickly easing depression, doesn’t actually do the job itself. Instead, depression relief comes from one of the drug’s breakdown products, a new study in mice suggests. The results, published May 4 in Nature, identify a potential depression-fighting drug that works quickly but without ketamine’s serious side effects or potential for abuse.

The discovery “could be a major turning point,” says neuroscientist Roberto Malinow of the University of California, San Diego. “I’m sure that drug companies will look at this very closely.”

Depression is a pernicious problem with few good treatments. Traditional antidepressants don’t work for everyone, and when the drugs do work, they can take weeks to kick in. Ketamine, developed in the 1960s as a sedative for people and now used commonly by veterinarians to knock out animals, can ease depression in minutes, not weeks, small studies show.

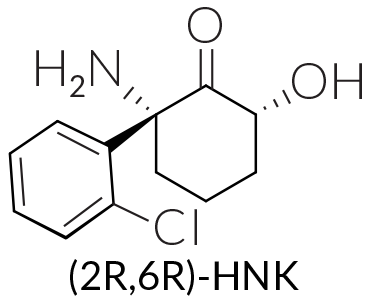

But the new study suggests that a metabolite of ketamine — not the drug itself — fights depression. Inside the body, ketamine gets converted into a slew of related molecules. One of these breakdown molecules, a chemical called (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, is behind the benefits, neuropharmacologist Todd Gould of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and colleagues found.

On its own, a single dose of (2R,6R)-HNK reduced signs of depression in mice, restoring their drive to search for a hidden platform in water, to try to escape a shock and to choose sweet water over plain. A type of ketamine that couldn’t be broken down easily into HNKs didn’t ease signs of depression in mice. Finding that a breakdown product, and not ketamine itself, was behind the results was a big surprise, Gould says.

That surprise could turn out to be valuable. Ketamine comes with serious side effects for people — hallucinations, floating sensations and clumsiness, for example. And at high enough doses, the drug is an anesthetic. But (2R,6R)-HNK may avoid these problems, experiments on mice movement indicate. “It’s actually pretty amazing how high a dose we went up to and didn’t see any ill effects,” Gould says. And since ketamine has already been used to treat depression, he says, the breakdown product has been inside people with no apparent ill effects.

Gould says that the behavioral improvements and lack of side effects make him optimistic that (2R,6R)-HNK can be developed into a safe and effective antidepressant. He and his colleagues plan to test the ketamine metabolite in clinical trials of people with depression.

A potential concern is that because of ketamine’s ability to warp perceptions, it is sometimes used as a recreational drug of abuse. But the metabolite may not have the same allure. Mice will push a lever to self-administer ketamine, but don’t seem as eager to up their dose of (2R,6R)-HNK, the team found.

More experiments are needed to show specifically how (2R,6R)-HNK affects the brain. One of the main explanations for how ketamine itself works is that it blocks NMDA receptors, proteins that sit on particular nerve cells and help strengthen neural connections. But (2R,6R)-HNK has nothing to do with NMDA receptors. If the new results are right, they suggest that NMDA receptors aren’t a good target for an antidepressant drug. “We thought it was one thing but now it seems like it’s something else,” Malinow says.