SMART EDITS RNA editing may have made cuttlefish (shown) and related cephalopods intelligent, but has slowed their evolution, new research suggests.

Roger Hanlon

Octopus, squid and cuttlefish don’t always follow the rules laid out in their DNA. Straying from prescribed genetic instructions may have increased the cephalopods’ thinking prowess, but comes at a cost, a new study suggests.

Once genes have been copied from DNA into RNA, these cephalopods heavily edit the genes’ protein-making directions, researchers report April 6 in Cell. The study involved a squid species, two octopus species and a cuttlefish species, all coleoids, or shell-less cephalopods. Each contained between 80,000 and 130,000 RNA sites that had been edited. This high level of editing contrasts with only 1,150 edited sites in RNA from a nautilus and 933 in a mollusk.

RNA editing changes one of the information-carrying subunits of RNA from the nucleotide adenosine to one called inosine. That substitution can change how a cell reads the genetic instructions to build proteins, exchanging one amino acid for another not specified by the DNA instructions. Generally, such tweaks to proteins have harmful effects, and evolution has gradually weeded out the changes. In the brains of humans and other mammals, fewer than 1 percent of RNA editing sites change protein-coding instructions.

But squid, octopus and cuttlefish edit about 11 to 13 percent of the protein-building RNAs in their brains, computational biologists Noa Liscovitch-Brauer and Eli Eisenberg of Tel Aviv University in Israel and colleagues discovered. Cephalopods edit RNA in other tissues, too, but not as much as in the brain.

Some genes contained multiple possible editable sites. Octopus and their brethren may edit all of the sites, or edit some but not others. Adding up all the edited and unedited combinations could produce hundreds to thousands of different versions of a protein within a cell. “It introduces immense complexity and diversity,” says Eisenberg.

All four coleoid cephalopod species share 1,146 editing sites in 443 proteins, the researchers discovered. Exactly why the species edit RNAs in the same place isn’t yet clear, but such sharing is a signal that editing at those sites was important in cephalopod evolution.

Open-and-closed case

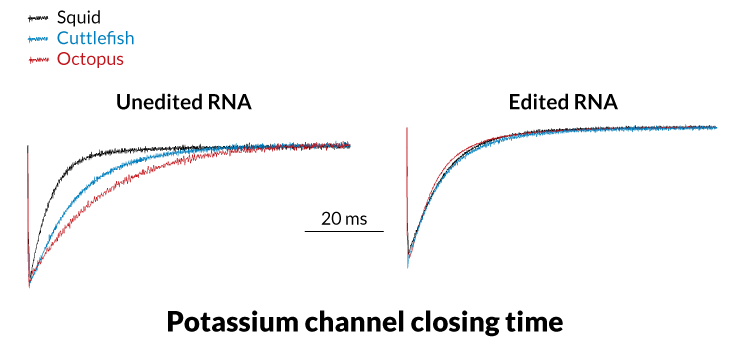

Researchers examined edited and unedited versions of a protein that regulates the flow of potassium in brain cells of a squid species (black line), cuttlefish (blue) and octopus (red). Potassium and other ions generate the electrical signals nerve cells use to communicate with each other. The unedited versions of the potassium channels (left) had different closing rates. But the edited versions (right) all close at the same rate in the different species.

Editing was especially prevalent in genes responsible for the structure and function of nerve cells in the brain, says coauthor Joshua Rosenthal, a neuroscientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. Such RNA editing could allow cephalopods flexibility in thinking, which could contribute to their complex behaviors such as unlocking cages or using tools, the researchers suggest.

Nautilus species are related to octopus, squid and cuttlefish, but aren’t known for their smarts. “Maybe it’s a genius that lays quiet,” says Eisenberg, “but [a] nautilus is dumb as far as we know.” Nautilus also tend not to edit RNA. That’s not proof that RNA editing contributes to cephalopod intelligence, “but it’s good reason to hypothesize,” says Eisenberg.

So much RNA editing comes at a cost, though, the researchers say. For an RNA to be edited, it must fold into complex shapes and have a stretch in which the single stranded molecule forms a double strand. DNA mutations that would impair the ability to form the double-stranded structures are not welcome near RNA editing sites, the researchers found. DNA mutations provide the genetic diversity needed for evolution, so limiting DNA alterations in favor of RNA editing has slowed evolution in these species. About 10 to 26 percent fewer DNA mutations than expected are found in RNA edited genes in coleoid cephalopods, Eisenberg and colleagues calculate.

The trade-off isn’t surprising, says evolutionary geneticist Jianzhi Zhang of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “There’s always a cost,” he says.

“Their data is clear in showing that RNA editing is important in those species,” he says. But while finding such high levels of RNA editing is “interesting and intriguing,” he thinks the researchers have not proven a connection between complex behavior and RNA editing. “The question is, ‘What is it doing?’ I don’t have an answer, but I think this is the most important question.”