Forget About It: How the brain suppresses unwanted memories

Not only can people intentionally forget disturbing memories, but they do so thanks to a pair of previously unreported neural processes, a new study finds.

Researchers have long argued about the existence of memory suppression and especially the ability to wipe out mental traces of traumatic events. A team led by psychologist Brendan E. Depue of the University of Colorado in Boulder has now found that a one-two neural punch fosters volunteers’ ability to forget upsetting scenes.

In early stages of intentional forgetting, part of the brain’s prefrontal cortex dampens activity in neural areas involved in visual and other sensory aspects of memory, Depue and his colleagues report in the July 13 Science. As the process of forgetting continues, a different prefrontal area quells the activity of structures implicated in conscious recall of information and emotions such as fear.

“The brain acquires multiple [ways] to reduce the likelihood of retrieving unwanted memories,” Depue says.

His team obtained functional magnetic resonance images of brain activity in 16 women during a forgetting experiment. Volunteers first learned to associate each of 40 strangers’ faces with a disturbing scene, such as a car crash. While viewing the same faces in a dozen ensuing trials, participants were instructed either to think of the previously associated images or to keep those images from entering their consciousnesses.

The researchers then tested the women’s ability to describe images that they had linked to each face. Those who had tried to remember the linked scenes recalled an average of 71 percent of the images, as opposed to 53 percent among volunteers who had tried to forget linked scenes.

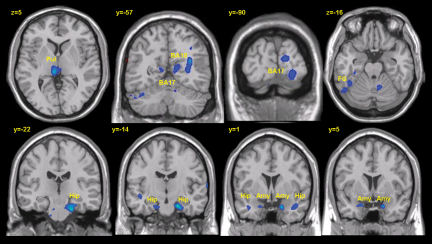

Brain images indicated that blood flow, a marker of neural activity, increased in a specific prefrontal area early during volunteers’ attempts at forgetting. At the same time, blood flow declined in the visual cortex and the thalamus, areas that handle sensory components of memory. The prefrontal cortex regulates these and other structures through networks of anatomical connections.

A different neural pattern eventually appeared among memory suppressors. Pronounced activity in another prefrontal area accompanied sparse blood flow in the hippocampus and amygdala, areas responsible for consciously recalled memories and fear conditioning, respectively.

The new results elaborate on a 2004 study, directed by psychologist Michael C. Anderson of the University of Oregon in Eugene, that implicated prefrontal areas in memory suppression. Anderson investigates intentional forgetting of disturbing words (SN: 3/17/01, p. 164).

Depue’s work shows for the first time that a neural emotion regulator, the amygdala, contributes to suppressing upsetting memories and that two neural mechanisms promote this process, Anderson says.

He regards memory suppression as a voluntary form of the defense mechanism known as repression. “These findings run counter to the general idea that traumatic memories are difficult, if not impossible, to suppress,” Anderson remarks.

Other new evidence indicates that the prefrontal region activated early in the attempt to forget upsetting scenes also participates in suppressing memory for information irrelevant to a current task, adds neuroscientist Anthony D. Wagner of Stanford University. His team’s findings appear in the July Nature Neuroscience.