New measurements have captured the universe’s expansion when it was slowing down 11 billion years ago, before a mysterious entity called dark energy took over and began spurring the cosmos to expand faster and faster. The measurements, reported online November 12 at arXiv.org, are an important step toward understanding what dark energy is and how it works.

About 15 years ago, astronomers discovered that the universe’s expansion is accelerating by cataloging spectacular stellar explosions called type 1a supernovas. Because each explosion emits almost exactly the same amount of light, astronomers can use a supernova’s observed brightness to determine its distance, and then measure its redshift, or how much its light is stretched, to determine how fast the supernova is moving away from Earth. Astronomers Adam Riess of Johns Hopkins University, Saul Perlmutter of the University of California, Berkeley and Brian Schmidt of Australian National University shared the 2011 Nobel Prize for their work using this technique to reveal that the universe’s expansion is currently accelerating and has been for the last 5 billion years or so.

But as bright as supernovas are, they are difficult to see deep in the cosmos, at distances corresponding to the time when the universe was only a few billion years old. So an international team of scientists with the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey, or BOSS, employs a different method. They use the 2.5-meter Sloan telescope at New Mexico’s Apache Point Observatory to collect light produced by feasting supermassive black holes that thrived a couple billion years after the dawn of the universe 13.7 billion years ago.

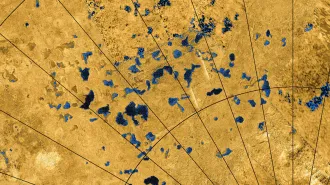

As that light makes its long journey toward Earth, it occasionally runs into clouds of hydrogen gas and gets partially absorbed. BOSS scientists crunched the data on the light of almost 50,000 black hole emissions to create a map of where those gas clouds are and, using redshifts, how fast they are receding.

Based on the speeds of the most distant of those clouds, BOSS scientists determined the universe’s expansion rate a mere 3 billion years after the Big Bang. The team then compared its measured rate with those from more recent eras to conclude that the universe’s expansion was slowing at that time. “The universe was a very different place,” says study coauthor and University of Utah physicist Kyle Dawson.

The BOSS finding is consistent with physicists’ theories of how the universe’s growth rate has changed. Immediately after the Big Bang, the universe ballooned rapidly in a split-second era called inflation. Expansion continued afterward, but like a coasting car, the cosmos had nothing to keep it accelerating. The gravitational attraction of all the matter in the universe was acting like rolling friction, gradually slowing down the expansion.

But as the universe got larger and matter got more diluted, scientists believe something began pressing the gas pedal again, causing expansion to accelerate once more. Scientists don’t know exactly what the culprit is, so they call it dark energy. Eleven billion years ago, dark energy made up less than 10 percent of the total content of the universe; today it makes up almost three-quarters.

BOSS and other surveys are allowing scientists to chart the universe’s expansion rate over time and determine the evolving role of dark energy. The measurements so far lend support to the leading theory that dark energy is a natural property of empty space: The more the universe expands, the stronger dark energy becomes.

Other theories posit that dark energy is a temporary phenomenon like inflation, and that matter’s gravitational pull will one day take over and temper the universe’s growth spurt. Still other physicists suggest that dark energy will cause runaway expansion, perhaps to the point that in several billion years it will pull apart galaxies, stars, planets, and even atoms in a doomsday scenario called the Big Rip.

“We can’t confidently predict the future of the universe,” Riess says, “until we get a ton of measurements about the past.” BOSS scientists are working toward that goal by collecting data from 100,000 more ancient black holes. Then they plan to upgrade to a larger telescope and survey more objects with a project called BigBOSS in 2017.