GLP-1 drugs failed to slow Alzheimer’s in two big clinical trials

Real-world data and anecdotal reports had hinted drugs like Ozempic could help

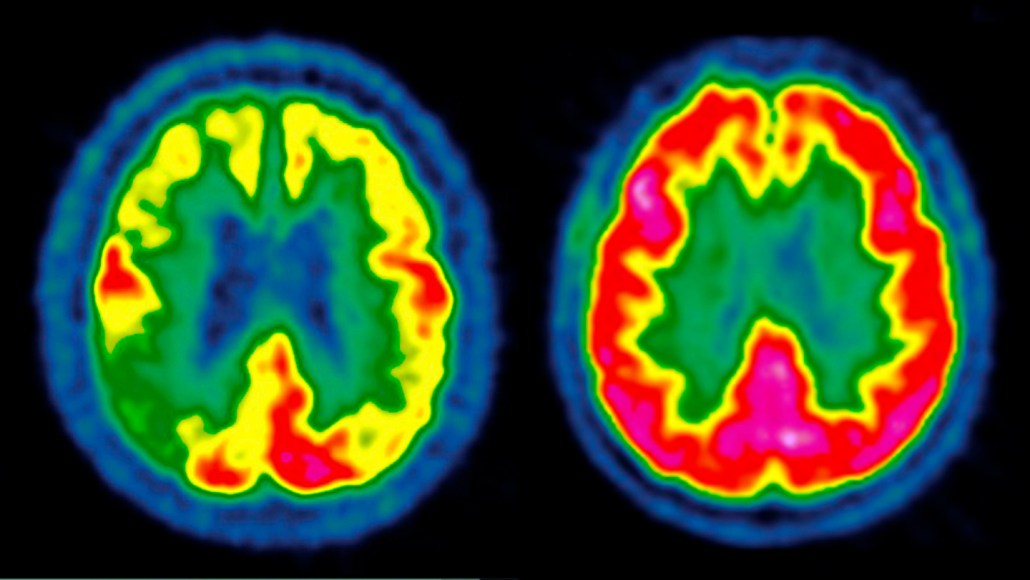

Scientists have previously shown that the brain of a person with Alzheimer's disease (left) can have diminished activity represented from low (blue) to high (red) compared with a healthy person (right). In two new clinical trials, scientists had hoped to delay disease progression by giving patients a GLP-1 drug, but the treatment failed.

CENTRE JEAN-PERRIN/Science Source

Two of the largest clinical trials of their kind have doused hopes that a diabetes and weight loss “wonder drug” might also work its magic on Alzheimer’s.

A daily dose of oral semaglutide did not delay progression of the neurodegenerative disease, the study’s authors reported December 3 at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference in San Diego.

The results are “very disappointing,” says Daniel Drucker, an endocrinologist at the University of Toronto who was not involved with the trials. His research laid the groundwork for developing semaglutide and other GLP-1 drugs, which are sold under the brand names Ozempic, Rybelsus, Mounjaro and others. Such meds had been hyped as something that “works for everything,” Drucker says. People in the field have questioned if there was anything GLP-1 drugs couldn’t do. “The answer,” he says, “is yes.”

The new results represent an “undeniable setback,” says Paul Edison, a neuroscientist at Imperial College London who was not part of the work. And they follow a recent blow from a clinical trial on GLP-1s and Parkinson’s disease that similarly showed drug treatment didn’t seem to help.

Scientists have not given up on the drugs for these conditions , but they will need to pivot, focusing on new GLP-1 research questions spurred by the trials’ results. That could include figuring out the best dose, timing and population for treatment — and even back-to-the-drawing-board ideas, like how to develop new drugs that more easily pass into the brain.

Finding the answer to those questions will take time and a lot more research, Drucker says. Until then, scientists will need to reckon with the new reality facing GLP-1 meds as treatment candidates for neurodegenerative disease. “I don’t think the field is stopped in its tracks,” he says. But “we need to rethink our strategy and take a step back.”

Early hope

For years, GLP-1 medications have been heralded as miracle meds, and it’s no mystery why. Beyond helping people manage blood sugar levels and prompting sometimes vast amounts of weight loss, the drugs can also address all sorts of other ailments.

Scientists studying these drugs have reported improvements in cardiovascular disease, liver disease, migraines, sleep apnea and more. The meds may also decrease the risk of drug and alcohol use disorders. GLP-1 drugs, which mimic one or more gut hormones, act on the body in ways both known and yet to be discovered. They can suppress appetite, slow digestion and also seem to reduce inflammation. And some evidence suggests the drugs may protect the brain, too.

There’s reason for GLP-1 enthusiasm when it comes to treating neurologic disease, says David Standaert, a neurologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Excess sugar, or glucose, in the blood is a risk factor for both Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, he says, so “controlling glucose seems like that would be beneficial.”

Animal studies, anecdotal evidence and real-world data have hinted that the drugs might benefit people with cognitive disorders. And a small clinical trial in people with Alzheimer’s disease uncovered signs of slowed cognitive decline in those treated with the first generation GLP-1 drug liraglutide, Edison’s team reports December 1 in Nature Medicine.

Patients’ experiences on the drugs add heft to the idea. “People say, I feel sharper. My brain’s working better. I have less COVID brain fog,” Drucker says. But these anecdotal reports are “not a substitute for a well-powered, randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial,” he points out. That’s the gold standard for determining whether a particular treatment offers patients any benefit over a placebo.

As the new Alzheimer’s results show, there’s been a disconnect between the outcomes of large studies like these and other evidence pointing to potential benefits. Variations in study details, including the types of drugs studied and length and way they were taken, can cloud an already fuzzy picture. The GLP-1 drug lixisenatide, for instance, seemed to offer some slight protection from worsening Parkinson’s disease symptoms, researchers reported in 2024 in the New England Journal of Medicine. But nearly two years of weekly injections of the GLP-1 drug exenatide did not curb symptoms of the disease, researchers reported in the Lancet in February.

“These trials have been kind of a bust,” Standaert says. They’ve yet to really demonstrate that GLP-1 drugs can change the course of neurological disease.

Disappointing results

Alzheimer’s disease affects more than 7 million Americans, and scientists predict that number could nearly double by 2050. Despite intense research over decades, there’s no cure for Alzheimer’s, and the newest available treatments delay disease progression by only about 30 percent. “We definitely want to slow decline even more,” says Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The two new GLP-1 trials, called evoke and evoke+, included nearly 4,000 people with early-stage Alzheimer’s. Participants had an average age of 70 and took either a daily semaglutide pill or a placebo for about two years. Researchers tracked how the disease progressed in each person. In a subset of patients, they saw a slight decrease in some Alzheimer’s biomarkers, proteins that can indicate presence of the disease. They also observed a drop in a key inflammatory biomarker.

But that did not translate to clinical benefits, Jeffrey Cummings, a leader of the trials and a neurologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas said at the meeting. “We did not have the corresponding benefit on cognition that we had hoped for,” he said. On a test that measured changes in clinical dementia before and after treatment, there was no difference between the drug and the placebo.

Watching the actual data appear on the screen at the meeting was a bit depressing, Sperling says. “You could clearly see that [patients] had no clinical benefit whatsoever.” Sometimes when clinical trials offer disappointing results, she says, people question whether there were problems with the study’s design. “That was not the case here,” she says. “It was a very well-run set of trials that gave us a clear answer.” At this early stage of the disease, semaglutide was not enough to slow Alzheimer’s progression, she says.

The research team, which has had the results for only about two weeks, plans to do a deeper dive into the data and present more results at the Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases Conferences next year, Cummings said.

There’s a long list of reasonable explanations for why semaglutide may have failed, Drucker says. When it comes to neurodegenerative diseases, GLP-1 drugs may be more successful in a preventative role, rather than a therapeutic one. It’s also possible that participants’ disease had advanced too far for the drug to boost brain health. Or maybe semaglutide could serve as a therapeutic — but not enough of the drug slipped into patients’ brains to make a difference. “These are all things we don’t know the answer to,” he says.

The trials underscore fundamental challenges in developing treatments for brain disorders, Standaert says. One difficulty is that both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are relatively slow-developing conditions. That means scientists need large groups of people and long periods of time to observe a potential treatment’s effects.

Another challenge is that scientists still don’t know all the ways GLP-1 drugs act on the body and brain. They’re fascinating drugs for which scientists have already found many good uses, Standaert says, “but that doesn’t mean they cure everything.” At this point, he says, “I think we need to back up a little bit and ask ourselves, ‘How do these GLP-1s work anyway?’” Sperling echoes the thought. She’d like to better understand whether these drugs have clear biologic activity against Alzheimer’s disease.

Drucker says it’s important to acknowledge when GLP-1s fall short in clinical trials. That will help scientists paint a more realistic portrait of the drugs’ strengths and weaknesses as treatments for different diseases. He and others in the field were hoping that the drugs’ actions would translate into benefits for people with neurological diseases. But, he says, “we have to be honest enough in the GLP-1 field to admit when we have setbacks. And in Parkinson’s disease and in Alzheimer’s disease, we have had setbacks.”