Ozempic and Wegovy ingredient may reverse signs of liver disease

People on the diabetes and weight loss drug semaglutide saw improvements in a condition called MASH

The diabetes and weight loss drug semaglutide may also help people with a severe form of fatty liver disease called MASH.

Michael Siluk/Alamy

The diabetes and weight loss drug semaglutide may also reverse signs of liver disease.

That’s the headline result of a new clinical trial that tested the popular medication in patients with MASH, or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

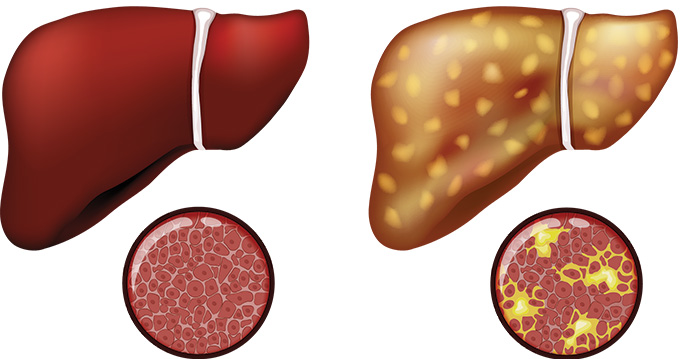

The disease is marked by fat droplets piling up in liver cells, chronic inflammation and scar tissue in the liver. But a 72-week regimen of semaglutide seemed to turn the disease around. Patients on the drug saw liver scarring improve and fat and inflammation wane, scientists reported April 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Scientists hope “the improvement in scar tissue will translate into less cirrhosis, and less of all of the bad things that can happen if scar tissue continues to progress,” says study coauthor Arun Sanyal, director of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. “That is the goal of treatment.”

Semaglutide, sold under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy, has become famous for treating type 2 diabetes and obesity, which are both risk factors for MASH. The drug may treat multiple conditions at once, says Grace Su, president of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Novo Nordisk, the company that makes Ozempic and Wegovy, plans to seek accelerated approval from drug regulatory agencies in the United States and the European Union. According to the company, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will review its application within six months. If successful, semaglutide would be just the second drug the FDA has approved for treatment of MASH.

The first, a medication called resmetirom, sold under the brand name Rezdiffra, was approved last year. These new drugs, and several others in the works, represent a leap forward for the field. Doctors who Science News talked to for this story emphasized the significance of the recent MASH progress, calling this era in the field a “watershed moment,” and the more than a dozen new medications in development a “tidal wave.”

Rezdiffra may have been the first drug FDA-approved for MASH, but in the next two to three years, Su says, there will be many more. “It’s going to be a flood.”

What is MASH?

MASH is a more severe form of the liver disease MASLD, or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. It’s a mouthful of a name that simply means too much fat is building up in the liver.

You may know the conditions by what they were called previously: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH. Those names weren’t all that accurate, though. Some patients with the disease do drink alcohol, for instance. And scientists wanted to avoid names with potentially stigmatizing language. “People don’t like to be called fatty,” says James Hamilton, a gastroenterologist and hepatologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

In 2023, a global consortium of scientists, doctors and patients changed NAFLD to MASLD and NASH to MASH. Whatever the name, one thing is clear: Too much fat in the liver can be dangerous. Some 25 percent of people with MASH may go on to develop liver cirrhosis, permanent scarring that damages the organ, and liver cancer, both of which can cause organ failure. In fact, Hamilton says, MASH is the leading cause of liver transplants among women in the United States.

Today, some 22 million or more American adults may be living with the disease. And experts predict that the number will keep rising.

What are the symptoms of MASH?

People often don’t know that liver damage can accrue with metabolic conditions like type 2 diabetes, obesity, insulin resistance and high cholesterol.

“Most people have absolutely no symptoms,” says Su, a gastroenterologist and hepatologist at Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor. When she diagnoses patients, they’re often taken aback. Many will ask, “How is that possible?” and say, “But I don’t drink alcohol.”

Some patients might experience mild pain on the right upper side of their abdomen. Others might feel fatigued. Still others may feel nothing at all. That’s why the disease is considered a silent condition, Su says.

“One of the scary things about liver disease is that for a very long time you have almost no symptoms,” Sanyal says. “And then suddenly, all hell breaks loose, and everything starts going wrong.”

Fat in the liver can lead to inflammation, scarring and cirrhosis. If semaglutide could prevent cirrhosis from developing, he says, it could halt the harmful symptoms that can accompany it, like “your legs swelling up so much you can’t tie your shoes, getting short of breath, vomiting blood, passing blood in your stools and developing cancer,” he says.

How do doctors detect MASH?

Detecting MASH is not as easy as swabbing your nostrils and waiting for a red line to show up on a test strip. Instead, doctors may discover it when they notice fat or scar tissue in the liver after a patient gets a scan. Or bloodwork might reveal enzymes that reflect injury to the liver.

A liver biopsy can paint a clearer picture. Healthy livers have distinct-looking sheets of rectangular-shaped cells, Hamilton says. In people with MASH, these sheets are not quite so regular. You can see fat inside the liver cells, as well as white blood cells that have infiltrated the tissue, a sign of inflammation. And woven between liver cells, scar tissue can form a mesh that looks almost like chicken wire, he says.

Still, liver biopsies, which involve threading a needle between the ribs to remove a bit of the organ’s tissue, can be tough on patients. And imaging comes with its own limitations. Even when doctors do see scan results that point to fat in the liver, that may not be enough to ring their alarm bells, Su says. Patients tell her “Oh, I have a fatty liver. My doctor told me it’s fine, don’t worry about it because it’s very common.”

“I’ve heard this over and over again,” she says.

How do doctors treat MASH?

Doctors know that losing weight via diet and exercise can halt or even reverse signs of MASH. “It’s just really hard to do,” Hamilton says.

In March 2024, the FDA approved resmetirom for MASH patients with liver scarring. The drug mimics the action of thyroid hormone and cranks up fat metabolism in the liver. In a clinical trial with nearly 1,000 participants, people on resmetirom were more likely to see improvement in their condition than those taking a placebo, researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Those are exciting results, Su says, but she points out that only about a third of people on the medication experienced a benefit. Scientists have been hunting for other drugs that could help. In June, the popular drug tirzepatide became another promising contender. Tirzepatide is already FDA-approved for diabetes (sold as Mounjaro), as well as for weight loss and now sleep apnea (sold as Zepbound).

After a year on the drug, people with MASH were more likely to see signs of the disease improve than those taking a placebo, scientists reported June 8 in a small clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine.

That’s in line with the new semaglutide trial’s results, which examined the effects of taking the drug or a placebo in 800 patients. Researchers found that 37 percent of people on the drug saw liver scarring improve, compared with about 23 percent on the placebo. And 63 percent saw their liver fat and inflammation go down, compared with 34 percent on the placebo. This part of the trial tracked participants for 72 weeks; a follow-up will run through 240 weeks.

What exactly the drug is doing to help the liver remains a mystery. Patients shedding lots of pounds could explain the organ’s loss of fat. But it’s not clear how semaglutide might work on liver scarring. “We don’t have all the answers,” says Stephen Gough, senior vice president at Novo Nordisk.

Scientists plan to report results from the second part of the trial in 2029, Gough says. That part will evaluate whether taking semaglutide lowers the risk of serious outcomes in patients, like the development of cirrhosis, liver failure, liver transplantation and death.

Other big questions remain, like whether the drug could also help people with other types of liver disease. “It’s possible,” Su says. “But there are a lot of unknowns.”

If these drugs do get approved for MASH, which Sanyal anticipates could happen before the end of the year, Su wonders how long patients would need to be treated. How will doctors assess success? How will they decide when patients can stop the medication? Those questions are important to figure out because the disease can be a lifelong problem, and, she says, “these are not cheap drugs.”