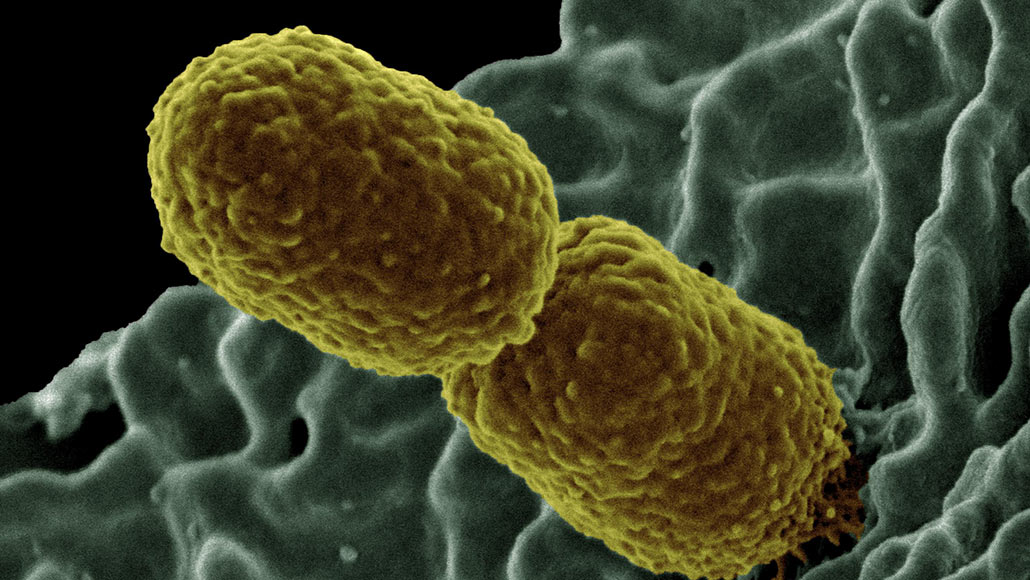

Common gut bacteria called Klebsiella pneumoniae (shown in yellow in a scanning electron microscope image interacting with a human white blood cell) can sometimes churn out alcohol, which may contribute to fatty liver disease in people who don't drink heavily.

NIAID/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)