How antibodies attack the brain and muddle memory

In mice, these immune molecules gone awry target a key message-sensing protein on nerve cells

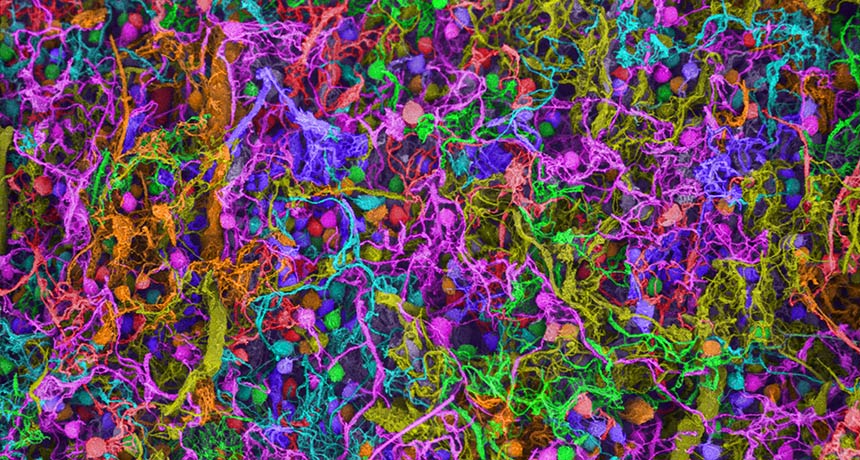

ATTACK OF THE ANTIBODIES This scanning electron micrograph shows a close-up of brain nerve cells. Antibodies that target nerve cell connections may interfere with vital brain functions such as memory.

Ted Kinsman/Science Source

Antibodies in the brain can scramble nerve cells’ connections, leading to memory problems in mice.

In the past decade, brain-attacking antibodies have been identified as culprits in certain neurological diseases. The details of how antibodies pull off this neuronal hit job, described online August 23 in Neuron, may ultimately lead to better ways to stop the ensuing brain damage.

Research on antibodies that target the brain is a “biomedical frontier” that may have implications for a wide range of disorders, says Betty Diamond, an immunologist and rheumatologist at Northwell Health’s Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y. “It’s beyond the idea stage,” she says. “It’s into the ‘It happens. Let’s figure out the why and the when.’ ”

Autoantibodies are a type of antibody that mistakenly target a person’s own proteins. One such internal attack comes from autoantibodies that take aim at part of the AMPA receptor, a protein that sits on the outside of nerve cells and detects incoming chemical messages. These autoantibodies interfere with the receptor’s message-sensing job, neurologist Christian Geis of Jena University Hospital in Germany and colleagues found.

The team purified autoantibodies from patients suffering from autoimmune encephalitis, a brain inflammation disease that causes confusion, seizures and memory trouble. When the researchers put these human autoantibodies into the brains of mice, the animals began showing memory problems, too. After the autoantibodies were infused into the mice’s cerebrospinal fluid or injected directly into the brain, the animals were worse at recognizing new objects placed in their cage than mice that didn’t receive the antibodies.

These mice also showed signs of anxiety, spending less time in wide open parts of a maze than mice that hadn’t received the human autoantibodies and preferring to hunker down in covered areas.

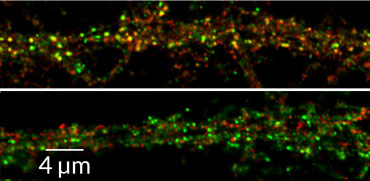

Experiments on mice and human cells in dishes revealed the nature of the brain attack. Autoantibodies attached to particular bits of AMPA receptors and then forced those bits to move inside nerve cells where they were no longer effective, Geis and colleagues found. This shift left the nerve cells worse at sensing chemical signals from other nerve cells, a deficit that might have caused the mice’s memory problems.

The details of this autoantibody brain attack might point out ways to help nerve cells under siege maintain communication, Geis says. Current treatments for autoimmune encephalitis are less specific, involving the removal of harmful antibodies from the blood or tamping down a person’s immune response.

Autoantibodies have been linked to a variety of other illnesses including lupus, autism and schizophrenia. But some of those results are difficult to interpret, Geis cautions. For instance, although studies have turned up autoantibodies in the blood of people with schizophrenia, some scientists have questioned how reliable those measurements are. What’s more, similar autoantibodies have been found in healthy people, results that leaves autoantibodies’ roles in schizophrenia and some other diseases murky.