Latest claim of turning hydrogen into a metal may be the most solid yet

If correct, the study would complete a decades-long quest to find the elusive material

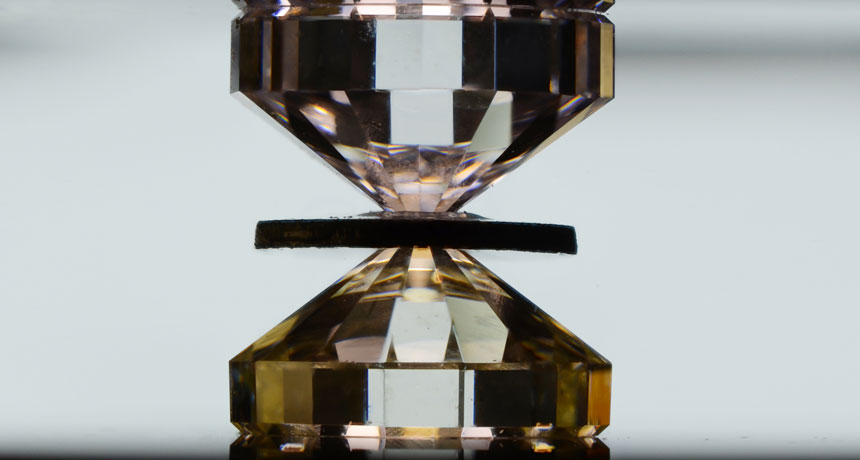

DIAMOND CRUSH Scientists used a device consisting of two diamonds (similar to this one) to squeeze hydrogen to extreme pressure. The element turned into a metal, researchers report.

D. Nishio-Hamane/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)