AUSTIN, TEXAS — Taking advantage of malaria strains battling each other could let doctors treat patients without encouraging more drug resistance, a lab test in mice suggests.

Without drugs, malaria parasites with no resistance to a medicine often can outcompete any pockets of drug-resistant parasites among them, Nina Wale of the University of Michigan pointed out June 18 at the Evolution 2016 conference. The drug-susceptible forms can hog resources and suppress the resistant ones. As drug treatments kill off the susceptible pathogens, however, the once-struggling drug-resistant minority can take over, creating a case of drug-resistant malaria.

As a new strategy for treating diseases without fostering drug resistance, Wale proposed intervening in the competition between parasite forms by weakening the resistant minority. Depleting resources needed more by resistant pathogens could let the susceptible ones wipe out the resistant ones. The result: Drugs can clear a malaria infection without a surge of resistance.

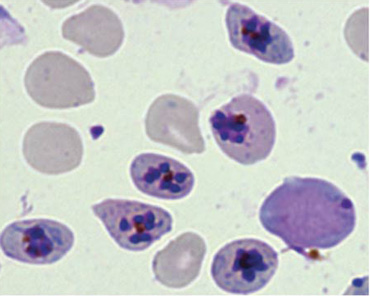

Wale has demonstrated the idea in a lab test with the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi. She injected each mouse with1 million parasites susceptible to the drug pyrimethamine and 100,000 resistant parasites. Without any drug treatment, the susceptible parasites keep the resistant ones from blooming into big numbers.

In the lab, P. chabaudi parasites grow better when researchers supply a compound called pABA. Both strains need pABA for synthesizing a component of DNA, but the drug-resistant minority need it more. When Wale failed to provide pABA to the infected mice, that deficit plus the competition was too much for the drug-resistant minority. They dwindled away even as pyrimethamine was attacking the susceptible ones. No drug resistance surfaced.

“Really exciting,” said evolutionary biologist Matthew Hall of Monash University in Melbourne Australia. “Obviously translating it will be challenging,” he added, but if researchers can find some way to deplete resources like this in real patients, he sees potential for the approach.