Little by Little

As food allergies proliferate, new strategies may help patients ingest their way to tolerance

Considering that food is full of foreign proteins, it makes sense that the intestine is the immune system’s version of Grand Central station. It’s the largest organ to regularly sweep up and annihilate molecules that don’t belong. And because food comes from outside, it’s no surprise that some people have allergies to it. The bigger mystery is why most don’t. Somehow during evolution, the immune system and food components developed a secret handshake that allows munchables to pass without a fuss.

Most of the time, that is. Once relatively rare, serious allergies to peanuts, milk, shellfish and other foods appear to be afflicting a growing number of children. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that food allergies now affect about 4 percent of American children, almost 20 percent more than a decade ago. Scientists have ideas to explain the increase — from children raised with too few germs exercising their immune cells to modern food processing that alters natural proteins and adds nonfood substances never before consumed in large amounts. Some studies implicate the use of certain vitamins and even childhood obesity.

Despite the growing problem, doctors have had little to offer beyond advising patients to avoid allergic triggers. Recently, though, studies have raised hope that new approaches might one day treat food allergies and perhaps even prevent the next generation from developing them. “I think we’re all encouraged that progress has happened relatively quickly,” says Robert Wood of Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore. Nonetheless, he cautions, a true, effective therapy is still years away.

If nothing else, the experiments have shown for the first time that curing food allergies is at least possible, even if the long-term prospects aren’t clear. Some children who began studies with immune reactions to even the smallest trace of peanut can now eat up to 13 nuts in one sitting. Similar dramatic gains have been seen for milk and egg allergies. Only a few children have been involved in each study so far, but researchers are cautiously increasing the number of enrollees and are emboldened to try other, more innovative methods.

“It’s the beginning,” says Andrew Saxon of UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. In a field with a history of false starts and disappointment, he says, “it’s the real beginning this time.”

Curing food allergies has been challenging, in part, because there are many ways to go wrong. No body process is simple, but the immune system is so terrifically complex that Nobel laureate Niels Jerne once likened it to a foreign language operating independently of the brain. Immunity (or allergy, which is essentially immunity run amok) involves legions of cells that not only chatter back and forth at lightning speed each time they encounter something new, but also remember their conversations for a lifetime.

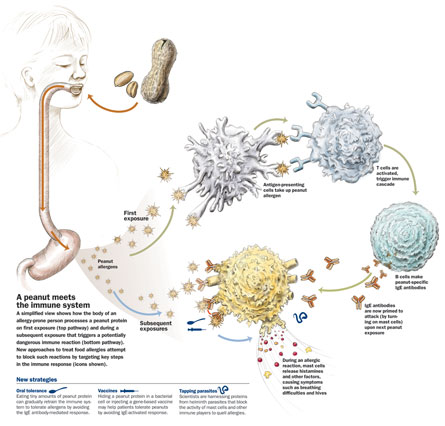

Simply speaking, when an antigen such as peanut protein passes through the digestive tract, it is first greeted by an “antigen-presenting” cell. This cell functions like a maître d’, escorting guests to their table and alerting the waiter. The waiters — it’s a fancy establishment, so there are more than one — are the T cells, which help the body recognize friend from foe. When food allergy develops, the T cells, instead of welcoming the peanut as the valued customer it is, initiate a process that alerts another type of immune cell, called a B cell. B cells make antibodies — the body’s bouncers. In the case of food allergies, B cells start to make IgE antibodies, which when bound to a peanut protein summon mast cells. Mast cells come armed with chemical weapons. Substances released from mast cells, including histamines and cytokines, lead to the most frightening symptoms of food allergies: hives, vomiting and anaphylaxis, which can be deadly. Once the IgE antibodies are on patrol, the peanut protein finds itself on the blacklist, and will be violently ejected by security should it try to return.

Second chance for a first impression

Treatments for pollen, cat dander and other nonfood allergies can slowly refocus the immune system, starting with injections of antigen in amounts too minuscule to provoke IgE antibodies and gradually increasing the dose. In the presence of minute amounts of the antigen, immune responsibility gradually shifts back to the more friendly reception of T cells and antigen-presenting cells. The problem is, attempts in the 1980s to treat food allergies with shots produced severe, even life-threatening side effects. The risks from treatment exceeded the risks from the allergy itself. “With that, we quit trying for a while,” says Wesley Burks of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

But as the number of children with food allergies began to rise, so did renewed interest in research. (The U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases alone increased funding for food allergy studies from $1.2 million in 2003 to more than $13 million in 2008.) Allergy experts spooked by the results of early experiments began to consider new approaches, among them giving allergy treatment orally rather than by injection.

Burks and others had long thought that the problem with previous treatment attempts was the shots themselves. Research suggested that the immune response to food particles introduced by mouth was safer and more likely to lead to tolerance. In 2003, for example, researchers writing in the New England Journal of Medicine noted that British infants were more likely to have peanut allergies if their skin had been exposed to creams containing peanut oil, instead of a first exposure through food. Experts believe that the human body is more inclined to tolerate substances introduced through the mouth, precisely because the digestive system must deal with the large amount of outside proteins in food and with the colonies of bacteria that live peacefully in the gut. “Understanding oral tolerance has been recognized as a key component in developing strategies for preventing and treating food allergies,” Burks writes in the August issue of Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

So guardedly, and under intense medical supervision, he and his colleagues began giving children infinitesimally small amounts of peanut powder to swallow (mixed with food), and increasing the dose in halting increments. In the August Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the researchers report that after months of treatment, 27 of 29 severely allergic children were able to eat about 13 peanuts. The most common reactions during the treatment were sneezing, itching and hives. Molecular analysis also revealed clues to explain how oral tolerance therapy might dampen the allergic response. Tests of the immune cells in the treated children found that after the experimental therapy, T cells were more likely to contain genes active in cellular suicide, or apoptosis, a finding that “is novel and may provide insight into the mechanism of oral immunotherapy,” the scientists write.

Tolerance to a T

Under the oral tolerance scenario, almost any food antigen could be a candidate for therapy. For example, in October 2008, Wood from Johns Hopkins and his colleagues released results of the first randomized trial using oral tolerance to treat milk allergy — a study of 20 children that 19 completed. At the beginning, no child could drink more than about one-fourth of a teaspoon of cow’s milk without a severe immune reaction. Writing in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the scientists reported that four months after starting treatment, children were able to tolerate from 2.5 to 8 ounces of milk. A follow-up published online in the journal this August described the experiences of more than a dozen children who were able to continue to gradually increase their intake of milk. While the results are encouraging, the team also noted that many of the children experienced side effects such as itching and hives that should be better understood before such a treatment becomes widespread.

Oral therapy isn’t the only way scientists want to try to reeducate the immune systems of allergic children. For example, studies will soon be underway with a vaccine that encapsulates modified peanut proteins in E. coli bacteria. With the protein tucked inside a bacterium, researchers hope to sneak in under the IgE antibody radar, but still alert the nonallergic components of the immune system. “By altering the peanut proteins just a bit, but in very specific ways, it is hoped that the IgE will not as readily see the vaccine,” says Scott Sicherer of Mount Sinai School of Medicine’s Jaffe Food Allergy Institute in New York City. Other modifications should improve safety and effectiveness, he says.

Meanwhile, the idea of giving food-allergy shots has even been revived. UCLA’s Saxon is trying to develop a genetic food-allergy vaccine — injecting not the peanut protein this time, but the gene that codes for it. The idea is to slip the gene into the maître d’/antigen-presenting cells and coax those cells to make the peanut protein. If the antigen-presenting cells produce the peanut protein robustly enough, the responsibility for the immune response might shift away from the IgE antibodies and mast cells.

“The idea of gene vaccines has been around a long time,” Saxon says. “The biggest bugaboo is getting it where you want.” If the introduced gene doesn’t find the correct cell, the protein won’t get made, or it won’t get made in the right place. However, in July, he and his colleagues described a molecule they believe can deliver the gene straight to the antigen-presenting cells. The idea is still being tested in mice.

Promise from parasites

Other future strategies take lessons from the past, by considering the origin of food allergies. Studies have long suggested that such allergies are a wayward version of the immune reaction to infection with human parasites such as helminths, the worms that cause river blindness, elephantiasis and other diseases. “If you study people in those countries where there are normally multiple parasites, the incidence of allergy is very low,” says Marie-Hélène Jouvin of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Yet when children are treated for parasites, she says, the tendency for allergy rises.

Parasites survive by manipulating the immune system to grudgingly allow their presence. Since a helminth attaches itself to the inside of the intestine, the parasite’s survival depends on creating a tolerant environment inside the body. One tactic was revealed in 2007: A research team led by scientists from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow reported in Nature Medicine that a substance isolated from a helminth was able to disarm mast cells.

Jouvin and her colleagues hope to soon receive approval to study a kind of oral therapy that might mimic the natural protection from food allergies that follows a parasitic infection. Using helminth eggs, researchers hope to test a treatment designed to trick the immune system into reacting as if it were accommodating a parasite (minus the actual worm), and tempering the mast cell response.

The helminth experiments would also be consistent with the “hygiene hypothesis,” one of the leading theories to explain the rise in the prevalence of allergies — that children raised in the indoor, antibacterial age lack the exposures to antigens of their ancestors, and so the children’s immune systems don’t always develop as nature intended. “Children are born with an immune system that is immature,” Jouvin says.

Other clues, too, point to food allergies as a consequence of an immune system too bored in early life. Parents are often advised to avoid giving children foods that are particularly prone to causing allergies for about the first year of a child’s life. But many studies are questioning that conventional wisdom, including one described late last year in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Researchers examined the prevalence of allergies among Jewish children in Israel and Great Britain, finding that the British elementary school children had almost 10 times the risk of peanut allergies (SN: 12/6/08, p. 8). The biggest difference in diets? Israeli children are fed peanuts earlier and more frequently than British children. The researchers also note that in the Middle East, Asia and Africa, peanuts are generally consumed in infancy and peanut allergies are uncommon.

“Our findings raise the question of whether early and frequent ingestion of high-dose peanut protein during infancy might prevent the development of peanut allergy,” wrote an international research team funded in part by the National Peanut Board. “Paradoxically, past recommendations in the United States and current recommendations in the U.K. and Australia might be promoting the development of peanut allergy.” Some countries, such as Sweden, have now abandoned the advice to avoid the introduction of certain foods early in life.

American doctors remain wary about early exposure to allergy-prone foods, believing the information still isn’t conclusive enough to change official recommendations. “We will do the same things we’ve been doing until the ongoing studies have given us better guidance,” Burks says. In particular, doctors are awaiting the results of a large study underway in Great Britain, in which children are being randomly assigned to eat peanuts in infancy or avoid them until later (for more information, see www.leapstudy.co.uk). Only when these and other studies conclude will experts know whether the secret weapon against food allergies ultimately lies in the culprit itself.

Laura Beil is a freelance science writer in Cedar Hill, Texas.