The moon’s poles have no fixed address

Ancient volcanoes may have shifted lunar balance and sent surface spots wandering

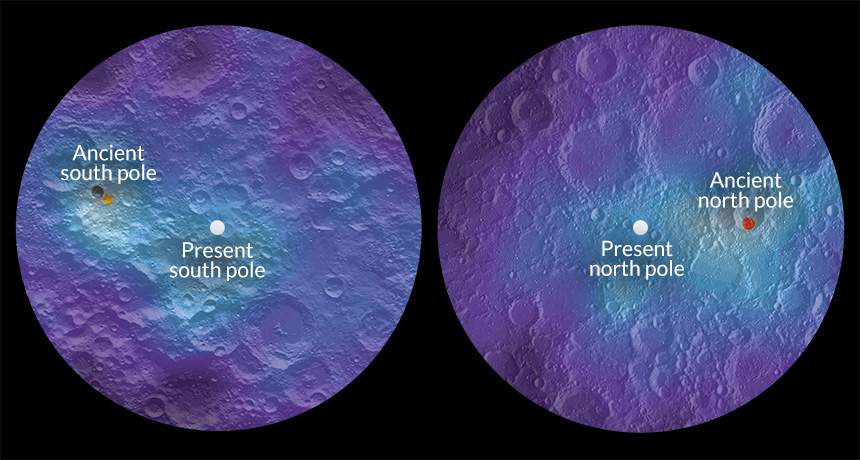

WANDERING POLES Deposits of hydrogen (white) mark where the moon’s poles used to be. The hydrogen, seen in these maps from the Lunar Prospector mission, is a proxy for water that froze in the ancient polar regions.

James Tuttle Keane