A rice weevil frozen in flight won the 2025 Nikon Small World photo contest

The annual competition reveals nature’s tiniest treasures

Zhang You

Through the lens of a microscope, even a dirty windowsill can hold some of nature’s tiniest treasures.

A staged snapshot of a rice weevil spreading its wings on a grain of rice won first place in the 2025 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition. Zhang You, a member of the Entomological Society of China, serendipitously stumbled upon the dead insect while cleaning his house. He captured the rice weevil’s posthumous final flight by stacking more than 100 photos from a high-resolution microscope.

The rice weevil (Sitophilus oryzae) is a pest that devours grains and seeds. You has witnessed rice infestations before, but discovering the dead beetle with its wings outstretched was a lucky find. “Their tiny size makes manually preparing spread-wing specimens extremely difficult, so this naturally preserved individual is rare,” You says.

He mounted the weevil on a grain of rice to emphasize its miniature scale. You, who is a first-time winner, hopes the photo can provide insights into the pests’ structure. “To me, a standout work blends artistry with scientific rigor, capturing the very essence, energy and spirit of these creatures,” he says.

The perched rice weevil is one of 71 striking photos recognized October 15 in this year’s competition. Here are a few of our other favorites.

A drop bursting with life

This translucent orb contains a multicellular universe.

German photographer and chemist Jan Rosenboom photographed hundreds of algae cells moving through a single water droplet. He used a 50-year-old microscope that he purchased at age 14 and LED lights to capture the image.

The algae (Volvox) blooms in freshwater ponds, lakes and puddles. The oval-shaped cells are outlined in green, while brighter green polka dots inside the outlines show the next generation of algae forming within each mother cell.

The droplet rests at a precarious angle on the tip of a syringe, depicting scale and capturing the perfect lighting. Rosenboom spilled more than 20 droplets before snapping the second-place photograph.

Showing the volume of life that can be found in a single drop of water can help people understand that even small worlds have biodiversity worth protecting, Rosenboom says.

Fluorescent ferns

Anatomist Igor Siwanowicz captured a vibrant cross-section of fern spores.

Spores are reproductive vessels like seeds, dispersed by wind or small animals. This fifth-place photo, lit up by fluorescent lasers in a confocal microscope, showcases three podlike structures, known as sporangia, where spores are housed and developed. The left pod shows a cross-section of spores, displaying brainlike shells. The center pod remains unopened, while the right pod is empty, having probably burst and dropped its spores during photo preparation, Siwanowicz says. The frond tissue of the surrounding fern (Ceratopteris richardii) is orange.

Siwanowicz enjoys the chaos of the image. “Microscopy images are very abstract and sometimes alien-looking, but they are a great way to create some interest among the broader public in nature and biology,” says Siwanowicz, of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Lansdowne, Va. “They’re confusing, but sometimes confusion creates this urge to find out more or to learn something new.”

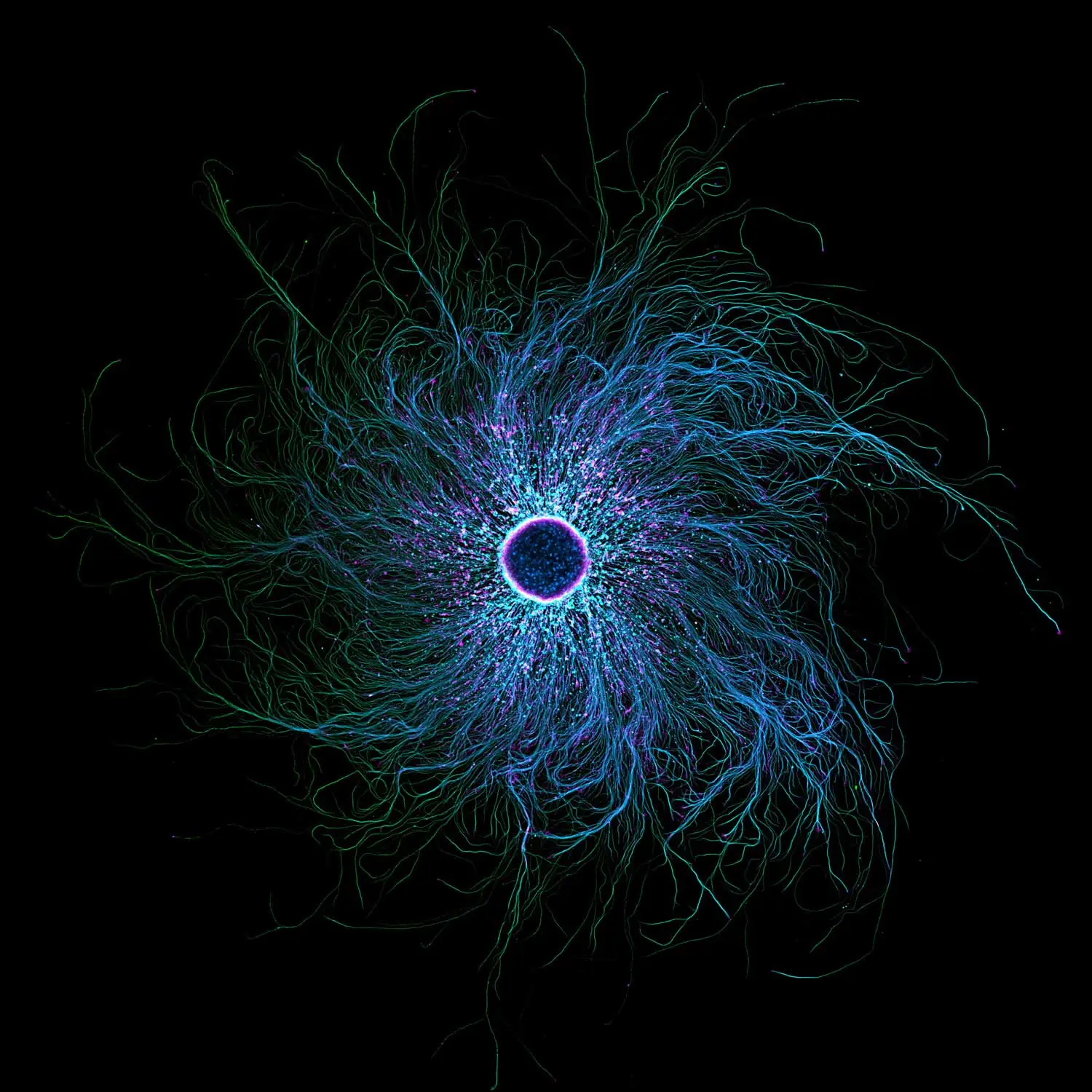

Sprawling neurons

These neurons may resemble an iris in an eye. But their spindly structures are designed to enhance touch, not sight.

Stella Whittaker, who took this photo as a biophysicist at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Md., studies the structure of sensory neurons. The wispy, rootlike arms help humans sense what is around them, she says.

The stunning photo highlights the swirling branches of sensory neurons, which can be found in the arms, legs and spine. Whittaker colored the image with antibodies and fluorescence using a confocal microscope, a tool that shines lasers at a specimen to eliminate out-of-focus light and produce high-resolution images. The pink, speckled dots highlight actin, a structural component that helps muscles contract. Microtubules, which act as highways for transporting organelles in and out of cells, are shown in blue and green. At the center, 10,000 cells group together.

Studying these neuron structures can help researchers understand how neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS and Alzheimer’s target microtubules, says Whittaker, who is now earning her Ph.D. at Weil Cornell School of Medicine in New York City.

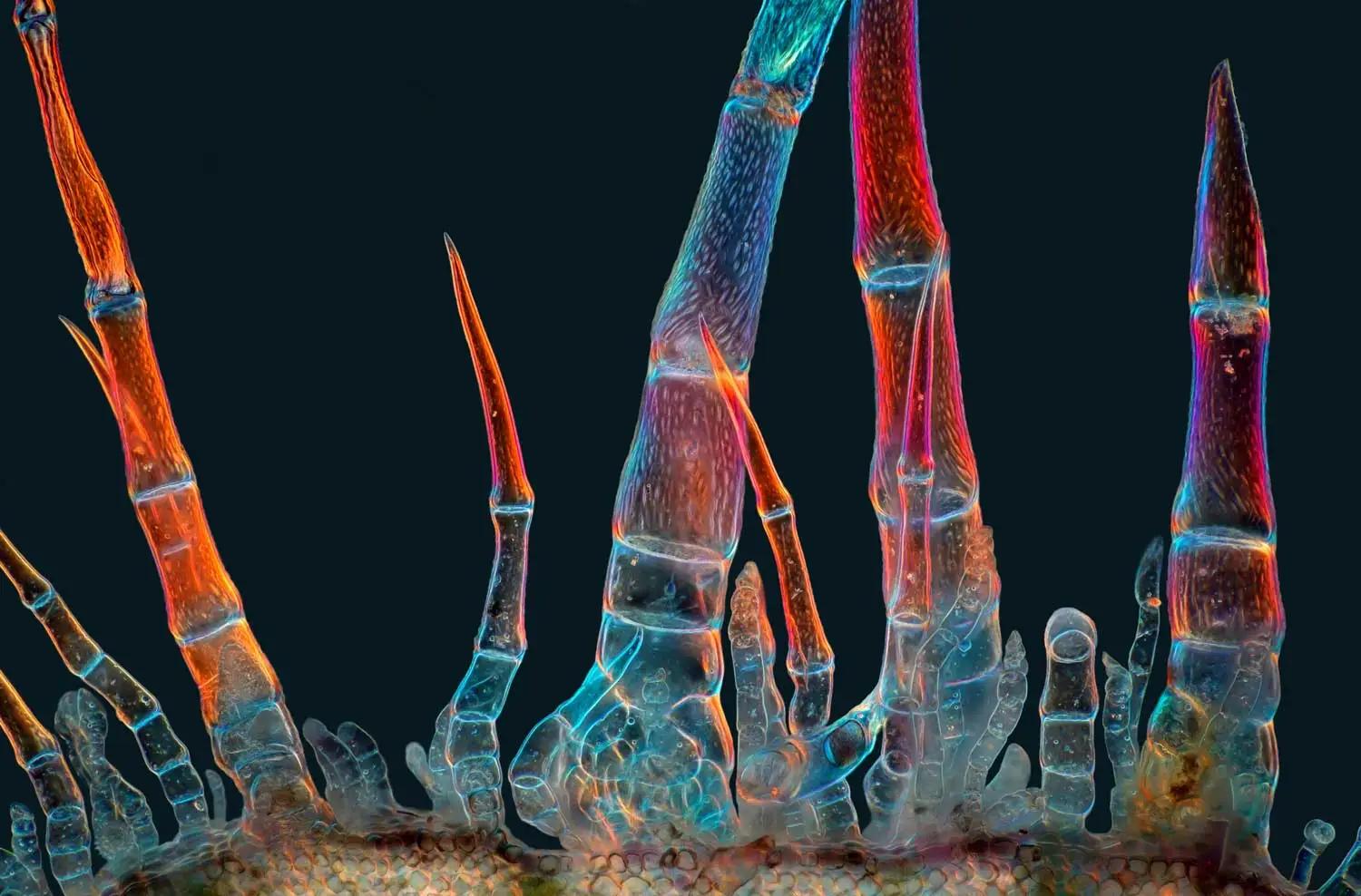

Sunflower hairs

Most people put sunflowers in water. But Marek Miś, a photographer and longtime nature lover based in Poland, couldn’t resist sticking slices of their bristly tissue under his microscope.

These skeletal protrusions are trichomes, tiny hairlike structures that help protect sunflowers against invaders. Miś collected the trichomes from a flower’s stem. He then illuminated the samples with light passed through a homemade polarizing filter — a microscopy technique that restricts the orientation of light waves, changing how specimens reflect colors. The mesmerizing magentas and blues in the final image, stitched together from more than 100 photos, highlight how trichomes come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

“This photograph shows that trichomes are not all the same,” Miś says. “The sunflower, already a beautiful plant in itself, hides additional beauty that cannot be seen with the naked eye.”

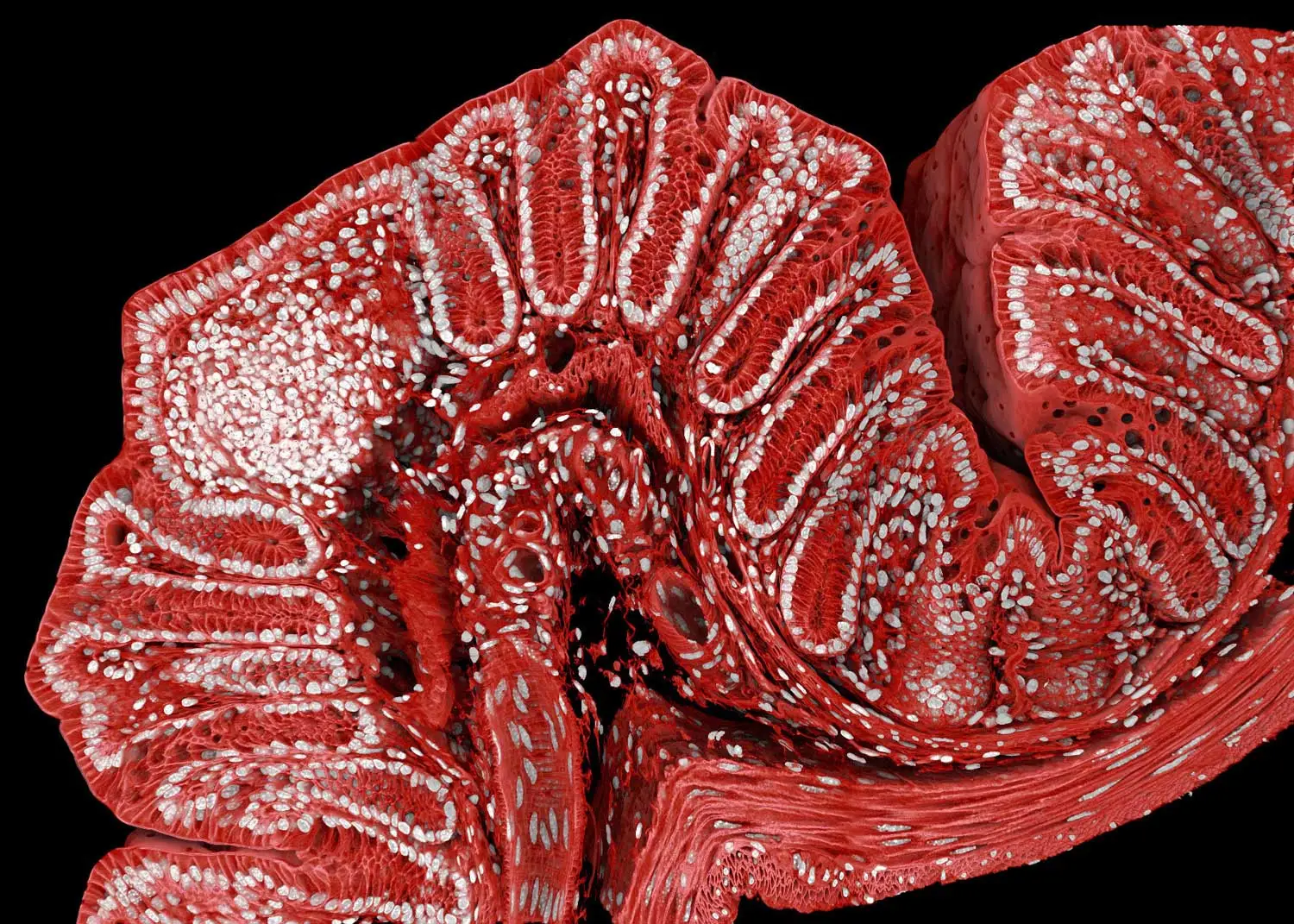

Tiny intestines

This photo of a mouse colon brings glamor to the gastrointestinal system.

Biologist Marius Mählen and his colleagues want to understand how tissue grows. “If you figure out the rules by which healthy tissue forms, then you will also start to understand why cancer tumors, for example, form very weird-shaped tissues,” says Mählen, of the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland. His team examines both mouse- and stem cell–grown organelles to see how maladies such as colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease might emerge in the body.

Over the course of one weekend, the team took 600 images of one mouse colon with a confocal microscope. They then stitched the images together to create the final picture. By adding antibodies and dye, Mählen and his team marked the cells in the image with different colors. The nuclei of the cells appear in white, while the cell membranes are red. The white clump toward the left marks a horde of immune cells monitoring for invaders.