A foot fossil suggests a second early human relative lived alongside Lucy

Bone fragments from Ethiopia show two human ancestors may have shared the same landscape

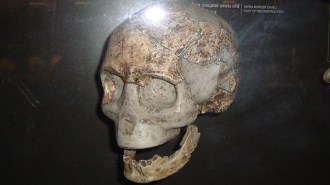

A partial foot skeleton from 3.4 million years ago has been assigned to the early human relative Australopithecus deyiremeda, a species that was first named in 2015 and challenges the traditional view of human evolution during this time.

Yohannes Haile-Selassie

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)

In 2009, Yohannes Haile-Selassie and his team were combing the desert landscape of Burtele, a paleontological site in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, when Stephanie Melillo found something remarkable: an ancient, humanlike foot bone.

“It was half of the fourth metatarsal ray,” says Haile-Selassie, a paleoanthropologist at Arizona State University in Tempe, referring to the bone that connects to the fourth toe. “When she came over and showed it to me, I just told her, go back, the other half should be there.”

Sure enough, Melillo, a graduate student at the time, found the other half. “That’s when I decided, okay, we’re going to have to crawl this area,” Haile-Selassie says.

Searching on hands and knees, the team ultimately discovered eight pieces of a partial forefoot from about 3.4 million years ago. Called the Burtele foot, the team concluded that the fossils were not from Australopithecus afarensis, an early human relative from the same time and place best known for the famous fossil skeleton Lucy.

Now Haile-Selassie and his team have gathered additional fossils from the Afar Region, and they determined that the Burtele foot probably belonged to a distinct species, Australopithecus deyiremeda, the researchers report November 26 in Nature.

“This is the most conclusive evidence to show that multiple related species coexisted at the same time in our evolutionary history,” Haile-Selassie says.

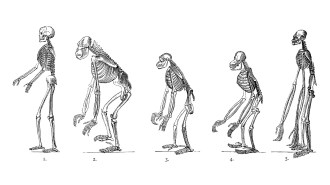

Paleoanthropologists have long thought that A. afarensis was the only early human relative living in this part of Africa between about 3.8 million and 3 million years ago. Represented by Lucy, the species has been viewed as “the ancestral species that give rise to everything else, the mother of us all,” says Fred Spoor, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London who wrote an accompanying Nature News & Views article.

A. deyiremeda was initially named by Haile-Selassie and coauthors in 2015 based on upper and lower jaw fragments found in the Afar Region, but at the time, the researchers did not think there was enough evidence to include the foot bones. Since then, the team has discovered more fossils closer to where the foot was found, including fragments of a pelvis, skull, jaw and additional teeth, which they also attributed to A. deyiremeda. The close proximity convinced the team that the foot must be from this species as well.

It is reasonable to assign the foot to A. deyiremeda, Spoor says. A. deyiremeda appears to have had more primitive features than A. afarensis, including a grasping big toe for climbing trees more easily. Certain features of the A. deyiremeda fossils resemble an earlier species Australopithecus anamensis, which lived between 4.2 million and 3.8 million years ago, more than they do A. afarensis.

Chemical analysis of A. deyiremeda’s teeth suggests it primarily ate plants from wooded areas, such as leaves, shrubs and fruits. That’s a less diverse diet than the combination of foods from grasslands and forests that A. afarensis consumed.

The dental features of the teeth attributed to A. deyiremeda show similarities to both A. anamensis and A. afarensis. This suggests A. deyiremeda may represent an intermediary stage between the two rather than a unique species, says Leslea Hlusko, a paleoanthropologist at Spain’s National Centre for Research on Human Evolution in Burgos.

“If you have this evolving lineage, it’s kind of exactly what you would expect: that there’s going to be some features of the earlier species and some features of the species that comes next,” Hlusko says. “And that’s what deyiremeda is. It’s really just this segment in between anamensis and afarensis, from my perspective.”

Hlusko also points out that the Burtele foot is incomplete. Considering that there is variation in the feet of A. afarensis, and there are no known foot fossils from the older A. anamensis, there is not enough evidence to say that the new bones come from a distinct species, she argues.

New species or not, experts agree that the picture of human evolution is far from complete. There are very few related fossils from 7 million to 4.5 million years ago, which could reveal more details about the split between chimpanzees and human ancestors, Spoor says. And there is a similar gap in the fossil record between 3.2 million and 2.8 million years ago, when the genus Homo is thought to have appeared, Haile-Selassie says.

Until more fossils are found, researchers can glean only a partial picture of human evolution from the fragmented remains of the past.