What Jane Goodall taught me about bones, loss and not wasting anything

Her legacy rests not just in stories of living chimps, but in the skeletons that endure

By Bruce Bower

Behavioral Sciences Writer

Primatologist Jane Goodall, who died on October 1, sits with a baby chimp named Zakayo the second at the Uganda Wildlife Education Centre in Entebbe in 2018.

Sumy Sadurni/AFP/Getty Images

Jane Goodall died on October 1 at the age of 91. When I heard the news, my mind raced back 35 years to a conversation I had with the pioneering observer and student of chimpanzee behavior.

As the ‘90s began, Goodall had been studying chimps in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park for nearly 30 years. Her work illuminated the previously unknown complexity of these apes’ social lives. But I was surprised to learn that the genteel-looking British ethologist had assembled a one-of-a-kind collection of chimp skeletons.

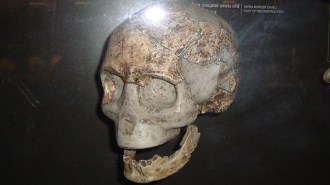

Goodall and her team retrieved the bodies of chimps within days of their deaths, placed the carcasses in a tin drum where insects pared down the remains, and then cleaned the bones. Each skeleton came from a Gombe individual with known sex, age, body weight and life experiences. That information let researchers investigate how individual development influenced the skeletal features of the apes.

Scientists who study ancient hominid fossils have no such luxury. They study the skeletons of strangers. Goodall’s project raised the possibility of analyzing our evolutionary ancestors from a new perspective, informed by insights into how the shapes of bones reflect the good, the bad and the ugly of an individual’s journey from birth to death.

Anxious to write about Goodall’s unusual skeletal pursuits, I called the Jane Goodall Institute. In 1990, email was not an option. Zoom was as realistic as a flying car. An institute official gave me a phone number to call in Africa. At the appointed time, I dialed the number. I heard a click. Jane Goodall said hello.

I took a deep breath and introduced myself. With a blessedly slowing heartbeat, I launched into a series of journalistic questions. Goodall spoke softly and avoided trumpeting the importance of her preservation efforts.

When I asked about the implications of Gombe chimp skeletons for understanding ancient hominids, such as Lucy’s 3.2-million-year-old partial skeleton, Goodall responded with blunt humility: “We just don’t know.” My queries about the reasons for the dramatic variations and quirks in the skeletal structure of Gombe chimps, revealed for the first time in her skeletal collection, elicited the same response. Perhaps speculation will turn into solid answers as research gets rolling, the famous chimp whisperer said.

Goodall became most animated when describing why she wanted not only to observe living chimps but also to preserve the bony frameworks of dead ones. I included the following quote in a 1990 Science News story: “I began collecting chimpanzee skeletons from the beginning of my research. When you’re working in the field, you shouldn’t waste anything.”

To my young ears, that approach seemed oddly pragmatic and detached. After all, Goodall made her bones, so to speak, forming close personal relationships with living Gombe chimps. But I could not have been more wrong.

Goodall’s connection to individual Gombe chimps probably deepened as their skeletons accumulated. Consider Flo, a dominant matriarch who was one of the first chimps to approach Goodall’s camp. Flo was an aggressive mover and shaker in the Gombe social scene, raising her five young with patience and affection. Flo’s death in 1972 hit Goodall hard.

True to her reputation as a Gombe influencer, Flo provided one of the most intriguing skeletal stories in Goodall’s collection.

Flo’s skeleton was larger than most at Gombe, male or female. Yet, she weighed less than a smaller but stockier male dubbed Charlie, thus demonstrating the difficulty of estimating body weights from bone sizes. And Flo experienced a pattern of bone loss unlike that of human females with osteoporosis, a condition associated with hormone loss after menopause. Flo’s skeletal strength coincided with Goodall’s field observations that this chimp matriarch had given birth within a few years of her death at nearly age 50. Only recently have researchers found evidence for menopause in female chimps that live past 50, an especially old age in the wild.

Flo’s anatomical afterlife, and those of her compatriots, taught academics about the intricacies of skeletal formation, which must have given Goodall great satisfaction. Even as advanced age moved Goodall away from fieldwork and into environmental activism and book writing, her refusal to waste anything as a young befriender of Gombe chimps continued to pay scientific dividends.

I like to think that if an afterlife exists beyond the scientific kind, Jane Goodall and Flo are gazing at each other with renewed affection.