A glimpse inside a gecko’s hand won the 2022 Nikon Small World photo contest

The annual competition showcases snapshots of miniature marvels

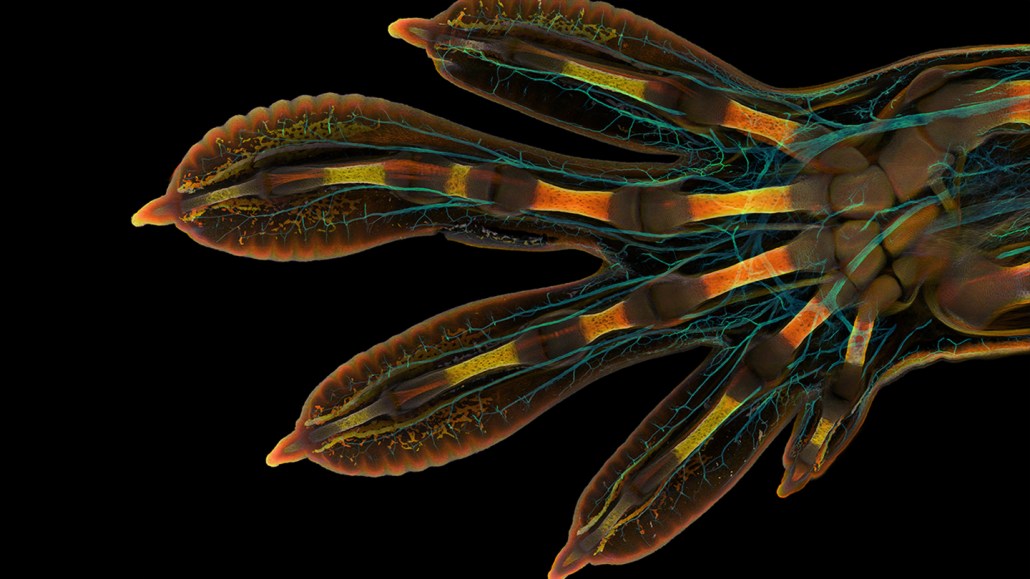

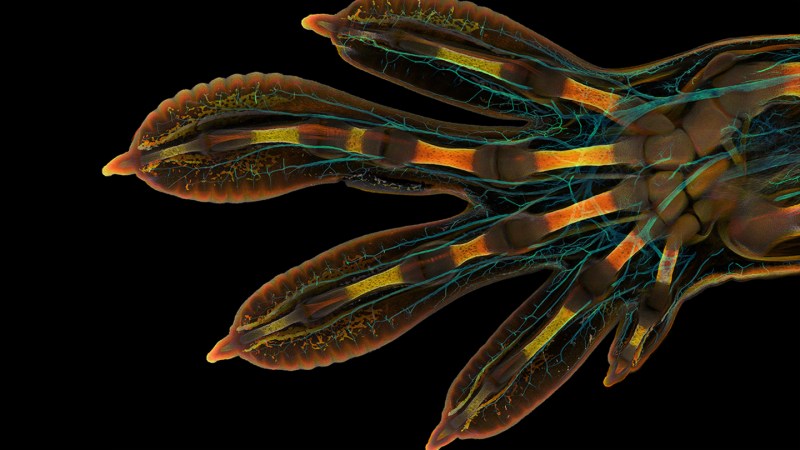

This image of the hand of an embryonic Madagascar giant day gecko, shown at 63 times magnification, displays cyan-colored nerve cells. Collagen appears yellow to orange.

Grigorii Timin and Michel Milinkovitch/University of Geneva, Nikon Small World

Life is beautiful at all scales, from big to small. Sometimes that splendor is concealed beneath literal scales.

A mesmerizing peek below the developing scales on the hand of an embryonic Madagascar giant day gecko (Phelsuma grandis) won first place in the 2022 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition. The winning image, stitched together from hundreds of images taken over two days with a confocal microscope, was crafted by University of Geneva researchers Grigorii Timin and Michel Milinkovitch. The pair study the genetics and physics of embryonic development.

The hand is artificially colored to show budding nerves in cyan and structures containing collagen in a range of oranges and yellows. Collagen is a building block of life, says Milinkovitch. Knowing where collagen is can help researchers better understand how bodies and tissues develop.

Tap this image and those below to enlarge

Parts of bones that have started to calcify shine brightest in the image, Timin says. Developing tendons and ligaments stretch as orange branches. Blood cells form clusters or line up inside new blood vessels at the tips of the gecko’s digits.

The image highlights beauty of all sizes, Milinkovitch says. The snapshot is “beautiful as a hand, you see this beautiful pattern of the fingers. Then you zoom, you see the spongy bones. And you zoom, you see the tendons. And you zoom, and you see the fibers that’s from the tendons. Then you zoom, and you see the blood cells.”

The gecko photo is one of 92 incredible images recognized in this year’s competition. The winners of the 48th annual contest were announced October 11. Here are some of our other favorites.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

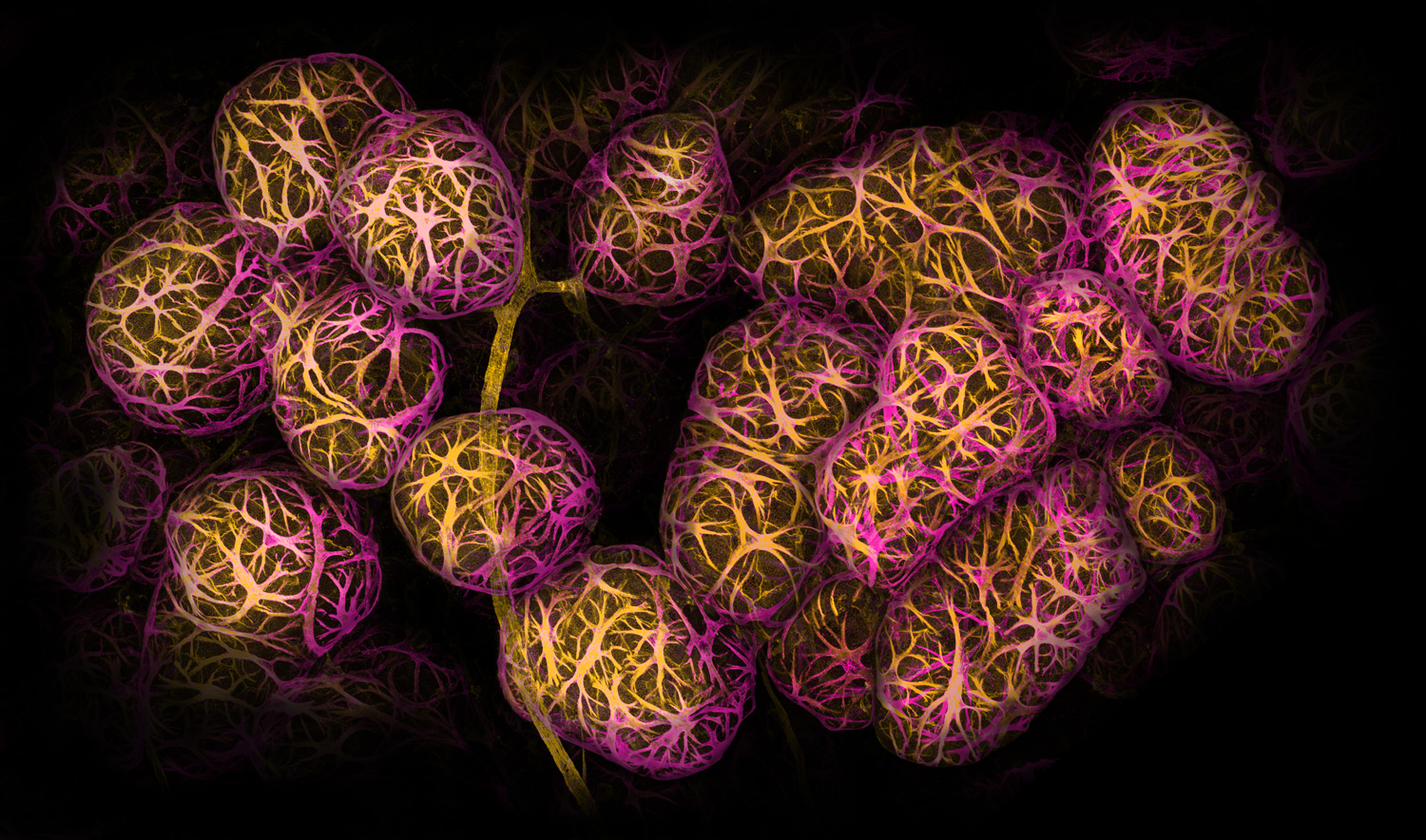

Got milk?

From a distance this photograph may look like a cluster of grapes. But each orb is a sprawling clump of cells inside breast tissue.

Cancer immunologist Caleb Dawson of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Parkville, Australia, took thousands of images using a confocal microscope to view tiny, musclelike cells that wrap around milk-producing spheres. He used dyes and antibodies to mark the cells yellow and magenta in this second-place-winning image.

The cells respond to the hormone oxytocin, Dawson says. Oxytocin is released during breastfeeding and helps squeeze milk out of the spheres, called alveoli. Such images of lactating breast tissue can help researchers figure out how immune cells keep breast tissue and the babies it can feed healthy.

Snuffed candle

Ole Bielfeldt had to be quick to capture the last gasp of an extinguished candle.

Candle wax is made of hydrogen and carbon atoms, which turn mostly into carbon dioxide when lit on fire. But not all those hydrocarbons burn, instead accumulating as soot on surfaces close to the candle. “When the flame goes out, the glowing wick has enough heat left to break up the wax molecules for a while, but not enough to burn the carbon,” says Bielfeldt, a photographer in Cologne, Germany. “So you get a trail of smoke until it cools.”

Using a fast shutter speed and a bright LED light, Bielfeldt managed to capture those unburned particles of carbon drifting away, earning sixth place.

Iridescent slime mold

Hidden on leaves and decaying logs in moist forests are minuscule works of art like these Lamproderma slime molds.

In the dappled sun of an October day, photographer Alison Pollack of San Anselmo, Calif., saw a sparkly leaf as she was digging through a leaf pile. After taking the leaf home and looking through a microscope, she was transfixed by the crinkly heads and iridescence of slime mold. Around 40 hours of work and 147 combined images later, Pollack had captured a striking snapshot that she likes to anthropomorphize as a nurturing relationship: parent and child, two lovers, or brother and sister. The photo earned fifth place in the contest.

Most slime molds have smooth heads, which release spores into the environment to reproduce. This pair may have dried too fast, stunting their development and leaving their heads wrinkly, Pollack says. But that’s OK, “because the texture to me is just gorgeous.”

A deadly predator

All fear the predacious tiger beetle, especially this poor fly.

Murat Öztürk of Ankara, Turkey, nabbed 10th place in this year’s competition with an astounding — and unnerving — snapshot of a tiger beetle using its mandibles to crush a fly by its eyes.

Tiger beetles (Cicindelinae) sprint after their prey so quickly that the insects go temporarily blind. The photographed beetle would have stopped multiple times to orient itself to figure out where the fly was, eventually snatching its meal. Thanks to the beetle’s strong and sharp jaws, “the chances of survival of the creatures caught by this insect are very low,” Öztürk says.

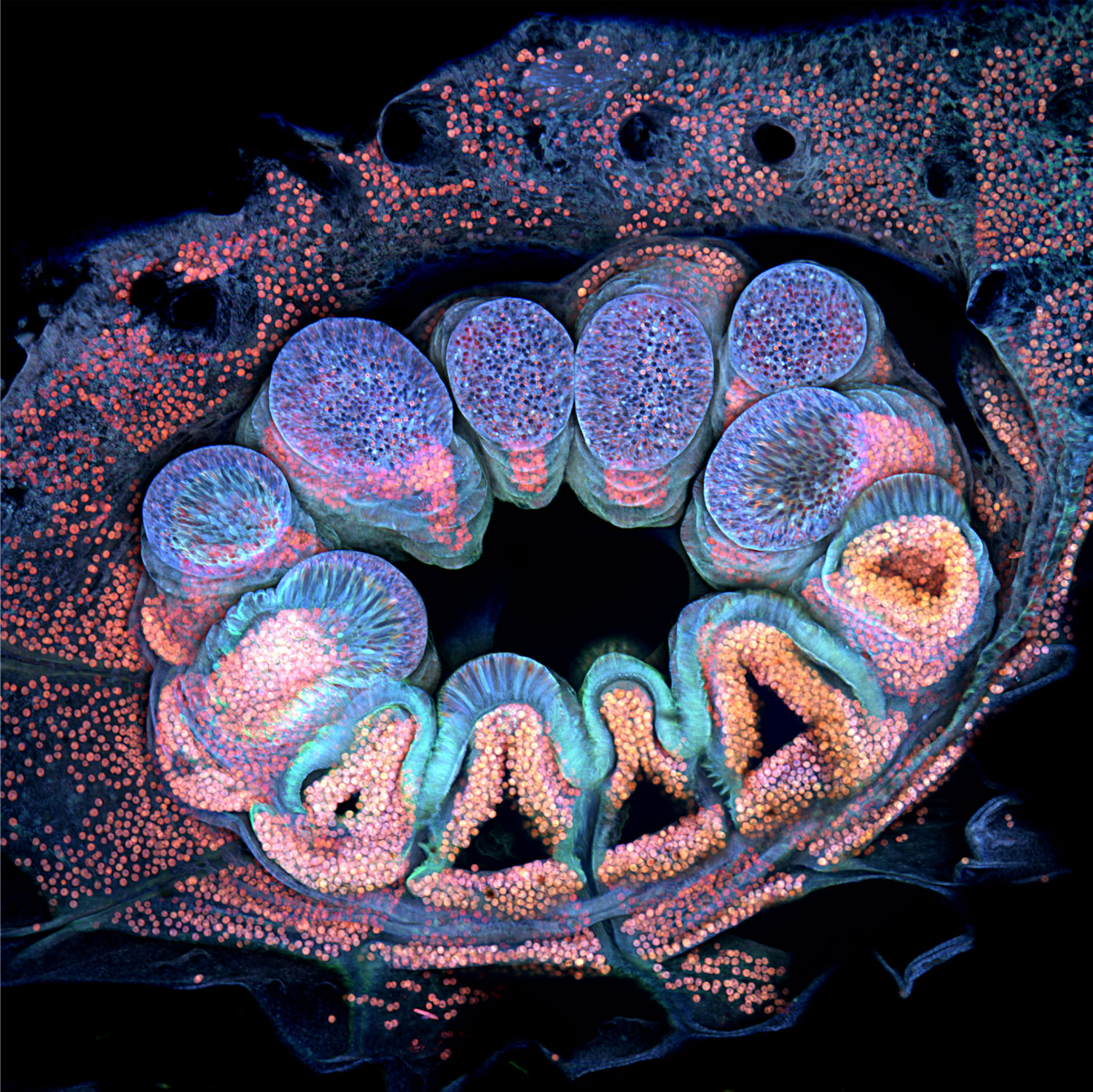

Coral close-up

In Opal Reef off the coast of Australia, some cauliflower coral (Pocillopora verrucosa) polyps appear green. But the same organism is transformed when viewed under a microscope in the lab.

To reveal the polyp’s individual cells, marine scientist Brett Lewis of Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, stitched together more than 60 images taken over 36 hours. The coral naturally fluoresces a medley of blues, purples and pinks when exposed to different wavelengths of light. Algae living inside the polyp appear orange or pink, while the coral’s tissues shine blue. The image won 12th place in the competition.

One amazing thing about the photo, Lewis says, is that in some areas, algal cells shine through a light blue haze. That’s because coral tissue is transparent; algae give coral its color.

Peeks of coral’s internal makings can help scientists understand its biology, Lewis says. His work, for instance, aims to figure out how young polyps build strong foundations when they attach to a surface — an important step in building or restoring coral reefs.