Old drug, new tricks

Metformin, cheap and widely used for diabetes, takes a swipe at cancer

A NEW TRICK Known as goat’s rue, holy hay, French lilac and Italian fitch, Galega officinalis was an ancient herbal remedy. Now its derivative, the diabetes drug metformin, may find new uses treating cancer and other diseases.

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, adapted by M. Atarod

Like an aging actor rediscovered after being typecast for years, the long-standing diabetes drug metformin is poised to reinvent itself. A wealth of studies suggests the drug has cancer-fighting properties, and clinical trials are now under way to prove it.

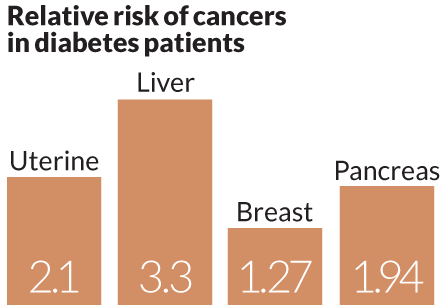

Metformin’s impact could be huge. “We believe that if this drug works, it will save between 100,000 and 150,000 lives a year worldwide because it is readily administered in countries that don’t have a lot of money for drugs,” says Vuk Stambolic, a molecular biologist at the University of Toronto. Also encouraging is the wide array of cancers metformin may treat — uterine, liver, pancreatic, colon, lung, ovarian and breast. Metformin may even help prevent cancer in people at high risk.

Metformin, also sold as Glucophage, has a long safety record and side effects that are milder than most cancer drugs. It is easy to store and take because it’s a pill, not an injection. As a result, metformin is on a fast track to clinical testing. Even while some scientists are still testing metformin in the lab, others are already pitting it against placebo in breast cancer patients.

In addition to getting repurposed as a cancer therapy, metformin shows great promise in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome (see sidebar below). Other recent studies hint that it might counteract dementia and Parkinson’s disease, and trigger growth of nerve cells. And early studies in animals suggest the drug could even extend life.

Yet metformin seems an odd candidate for the spotlight. It is an old medication, a generic that sells for less than a dollar a dose. Even if the drug gets cleared to treat cancer, don’t expect to see it featured on TV in expensive, slow-motion commercials. You won’t be hearing, “Ask your doctor about metformin.” At the clinic, no well-dressed drug reps will be passing out free samples.

The drug is also unlikely to ever get top billing in the chemo credits. Instead, metformin is being cast in a supporting role, the kind of medication given along with standard cancer drugs to attack a tumor from multiple directions.

If it works, says Michael Pollak, an oncologist at McGill University in Montreal, “it would be a nice story. You buy it by the kilogram.” That’s in contrast to most new cancer drugs, which must plow through years of expensive trials before they reach a druggist’s shelf. That translates into costs of tens of thousands of dollars for a standard treatment regimen of drugs such as bevacizumab (Avastin) and cetuximab (Erbitux).

Unexpected tumor fighter

On the surface, a diabetes drug would seem to offer little for cancer patients. But people with diabetes are more likely to get cancer. And various lines of research have revealed an often-overlooked connection between the two diseases.

That report from the University of Dundee in Scotland looked like a head-scratcher until an avalanche of similar findings followed. Researchers at the University of Alberta in 2006 found that patients who had diabetes and cancer were less likely to die if they were taking metformin, compared with patients getting insulin or another diabetes drug.

The metformin effect showed up again in 2009 when Ana Gonzalez-Angulo, a surgical oncologist at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and her colleagues looked back at 155 breast cancer patients treated between 1990 and 2007 who also had diabetes. Fully 24 percent of the patients getting metformin had no detectable tumor after standard chemotherapy, compared with only 8 percent of similar patients not getting metformin.

“It’s hard to find a cancer that hasn’t had a [research] paper about metformin,” says Iris Romero, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago. She found in 2012 that patients with ovarian or related cancers who had taken metformin were substantially less likely to die of cancer-related causes over five years than similar patients not getting the drug. A Mayo Clinic study in the same year yielded similar results.

Epidemiological studies raise possibilities but don’t cure anyone, not even a mouse. “They give us the basis to see if we have enough evidence to move forward,” says Gonzalez-Angulo. That’s where randomized trials come in. More than 3,600 breast cancer patients who have been through surgery and/or chemotherapy have now been randomly assigned to get metformin or a placebo.

It’s a leap to go this quickly from population studies to a big randomized trial, but metformin’s record makes it the exception. “The general consensus was that this is an appropriate time to ask the question,” says Pamela Goodwin, the University of Toronto medical oncologist leading the trial. Dozens of smaller trials are testing metformin against other cancers.

Blocking growth

A fast-forward to the clinic hasn’t stopped scientists from pursuing molecular clues to metformin’s cancer-suppressing activity.

Metformin controls type 2 diabetes by lowering patients’ blood sugar levels, which reduces the need for insulin production by the pancreas. A hormone, insulin regulates cells’ uptake and use of the simple sugar glucose for energy, and people with diabetes or prediabetes often have cells that take up glucose inefficiently.

But cancer cells do just fine in a milieu of high glucose and high insulin. By lowering both, studies indicate, metformin indirectly inhibits cancerous growth in people. The drug also seems to attack cancer by a more straightforward route. Metformin can slam the brakes on cancer-abetting mechanisms at work inside cells by turning on a protein called AMP-activated protein kinase. By revving up the AMPK protein, metformin bogs down a troublesome growth-spurring protein called mTOR.

Metformin, Romero says, “has a very biologically plausible mechanism.”

The drug must get inside tumor cells to turn on AMPK, so the effect should show up in tissues that come into contact with lots of metformin. Metformin is an oral drug that must pass through the intestines before entering the bloodstream, Stambolic says. Colorectal cells are likely to encounter the drug, which puts colorectal cancer high on the list of diseases the drug could target.

That’s why researchers were impressed by the results of a study done at Yokohama City University in Japan, in which scientists used magnified colonoscopy to identify 23 volunteers without diabetes who had tiny clusters of abnormal tubelike growths in their rectal tissue. These growths are the earliest precancerous lesions found in colorectal tissues and some develop into polyps, which can turn malignant.

Nine of the volunteers were randomly assigned to get metformin. These people showed a drop in the number of growths from 8.8 on average to 5.1 after only one month of taking the drug. Fourteen other volunteers who didn’t get metformin over that time saw their lesion clusters remain practically unchanged, rising from 7.2 to 7.6, the researchers reported in Cancer Prevention Research in 2010.

Metabolic effects

But metformin also seems to have an effect on tumor cells that reside far from the colon, Stambolic says. In those cases, metformin apparently works by a roundabout mechanism — lowering glucose in the blood, which leads to less insulin production and contributes to weight loss.

People with diabetes are about twice as likely as those without diabetes to develop liver, uterine or pancreatic cancer, and diabetes patients also have some increased risk for breast, bladder and colorectal cancers. Enter metformin. People with type 2 diabetes usually make plenty of insulin, but it gets left in the blood because their cells resist its effects. Metformin relieves this insulin resistance by taking away some of the liver’s capacity to make glucose and dump it into the bloodstream, lowering demand for insulin production, Stambolic says. This mimics the benefits of calorie restriction (SN: 8/1/09, p. 9) and induces cells to process glucose more effectively.

Insulin promotes growth by turning on a biochemical pathway in the cell. Insulin’s progrowth signals can ultimately activate mTOR and shut down failsafe anticancer processes. By lowering insulin and glucose in the blood, metformin removes the punch bowl from this cancer party. If metformin does its job, less insulin reaches a cancer cell’s front door — the receptor proteins to which insulin binds to exert its effects.

This insulin pathway appears important in certain cancers. About 90 percent of breast tumors display insulin receptors, Stambolic says. And insulin can also interact with other cellular docking stations called IGF-1 receptors and abet cell growth. While not all tumor cells display a multitude of these receptors, Pollak says their presence or absence may clarify which patients would benefit from metformin. The drug might work best on tumors that are clearly responsive to insulin and in people with high blood glucose, he says, “so there is room for their insulin to fall.”

Romero agrees. “Metformin might be more effective in cancer where there’s a double whammy” of obesity and high blood glucose. “For gynecologists that would be uterine cancer.”

Alastair Thompson, a surgeon at the University of Dundee, says weight gain is linked with breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. And Stambolic points out that “more and more women who are showing up at clinics with breast cancer are obese.”

The good news: In Goodwin’s trial, early returns show the metformin group is losing weight.

Cancer by cancer

Many scientists are looking to metformin to help out in hard-to-treat cancers. For instance, some breast tumors don’t respond to standard drugs because they lack receptors for the hormones estrogen and progesterone and for the progrowth HER2/neu protein. But these triple-negative cancers often have one thing in common — active mTOR that’s stoking tumor growth, Thompson says.

Metformin seems to have other tricks up its sleeve, and one could benefit uterine cancer patients. Overexposure to estrogen can gin up cancer in uterine cells, but the effect is toned down by progesterone. When progesterone binds to its receptor protein on cells, it keeps estrogen-fueled growth in check. Metformin promotes progesterone receptor activation by suppressing mTOR, researchers in Beijing reported in 2011 in the Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Taking metformin might also prevent some cancers. Randomized cancer prevention trials are nearly impossible to do because they would need healthy people to take drugs or placebos for years to show an effect. But Romero says preventing ovarian cancer in a unique group of women — those carrying a mutation in the BRCA gene — might fit the bill. Women with a BRCA mutation face a sharply increased lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.

“Here’s how I see this coming into play,” she says. “The clinical trials approach BRCA-mutation carriers and suggest metformin as an option until their ovaries get taken out. They would lose a little weight. I think they would be really into it.”

Other frontiers

Quite apart from combating diabetes or cancer, metformin might find use in thwarting certain neurological diseases. For instance, type 2 diabetes seems to increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease, but when researchers in Taiwan tapped into a huge health database in 2012 they found no Parkinson’s increase in diabetic patients on metformin. Comparing only people with diabetes against each other, they found that those on metformin were less likely to develop Parkinson’s disease than those getting other diabetes drugs called sulfonylureas, the team reported in Parkinsonism & Related Disorders.

Metformin can also stimulate new neuron growth. The drug improved problem-solving and memory in mice negotiating a water maze, a U.S.-Canadian team reported in 2012 in Cell Stem Cell. Elsewhere, data are now being analyzed from a randomized trial in overweight people aimed at determining whether metformin preserves memory and general cognition.

On another front, metformin shows hints of extending life. Of 16,417 heart failure patients with diabetes who were discharged from hospitals, a Denver-based research team found in 2005 that 25 percent of those on metformin had died within a year, compared with 30 percent on another diabetes drug and 36 percent of those getting neither drug. Metformin also retards aging in worms and mice, albeit in higher doses than people get. The biological mechanisms underlying these observations are still being investigated.

A ‘dirty’ drug

Despite all the promising results, the buzz about metformin seems muted. At a cancer research meeting in Washington in April, the session on metformin was only half full.

Clinical trials aren’t done yet. Some scientists might think metformin will flop in its new role. And there is no assurance that the relatively safe doses used for diabetes will work against cancer. Besides, metformin isn’t worry-free. It can cause side effects such as intestinal bloating, muscle pain and diarrhea, especially when people first start on it. A less common but more serious side effect is lactic acidosis, marked by low pH in blood and tissues. Anyone showing it must stop the drug.

There’s just a lot about metformin at the cellular level that’s unclear, Pollak says. “We now have a mixed bag of very important clues that must be followed up, but they are only clues.”

Thompson sees a bright side there. “It’s a relatively ‘dirty’ drug, in the nicest sense,” he says. “It seems that it doesn’t work on only one molecule, and in cancer that can be quite beneficial.” Compared with other cancer drugs, “metformin might work more subtly, by gently suppressing, and not completely strangling, cancer tissues. And that might be a more sustainable effect.”

Meanwhile, metformin will keep its day job, hiding in plain sight as a diabetes drug prescribed to 120 million people a year worldwide.

Treating polycystic ovaries

Metformin has already established itself as a weapon against polycystic ovary syndrome, in which cysts enlarge the ovaries, leading to irregular menstrual cycles, lack of ovulation and hence low fertility. Women with the condition who do get pregnant face a heightened risk of complications.

While the cause of polycystic ovaries is unclear, roughly 40 percent of women with the condition are obese. Even more show insulin resistance. Both result in excess insulin in the blood, fingering insulin as a chief suspect in the condition. Since a 1994 study first suggested that metformin might help these patients, many reports have backed it up:

- A 2003 review of 13 studies by a British-Australian team found that the drug increases the chance of ovulating nearly fourfold in women with the condition.

- In 2011, researchers in Egypt and the Netherlands tracked women who got pregnant despite having polycystic ovaries. Those on metformin were one-sixth as likely to develop gestational diabetes and one-third as prone to a complication called preeclampsia as women not getting the drug.

- In Finland, scientists randomly assigned women with polycystic ovaries who had previously tried to get pregnant using fertility drugs to take metformin or a placebo. Women on metformin were substantially more likely to get pregnant and to have a live birth, the scientists reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism in 2012.

- While obese patients seem most apt to benefit from metformin, so can normal-weight women with polycystic ovaries, according to a 2011 randomized trial in four Nordic countries. Normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome who were using assisted fertilization were more likely to get pregnant if they were among those randomly assigned to get the drug.

Not all studies of women with polycystic ovaries find a benefit from metformin, and even the many positive findings haven’t led to regulatory approval for this condition. But that hasn’t stopped doctors from giving it to patients. In the United States, doctors can prescribe approved drugs for such “off-label” uses if they deem it necessary.

“Any OB/GYN on the street will tell you it’s one of the first-line treatments for polycystic ovary syndrome,” says Iris Romero, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago.