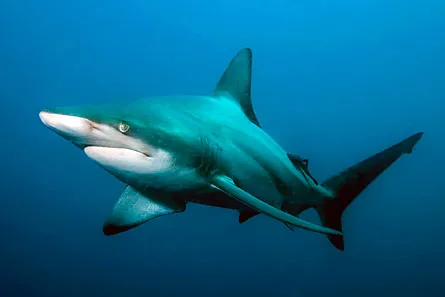

When male sharks are not available, female sharks may have a back-up option for reproduction — do it themselves.

“We still don’t know whether it occurs in the wild or would really have any significant impact on shark population rebounds even if it occurred relatively frequently,” comments Mike Heithaus, director of the Marine Science Program at FloridaInternationalUniversity in North Miami. Still, he says there is “a lot of interesting work to be done on shark reproduction — as this study illustrates — which is important in light of the collapses in populations.”

Chapman thinks that parthenogenesis can occur in the wild, but that it is less likely because there are more males. “The reason this has happened in captivity isn’t because there’s a change in their reproductive biology,” he explains. “It is more likely to happen if female sharks aren’t having enough dates,” he says. “These females did it because they were in captivity and ovulating.” In both confirmed cases of shark parthenogenesis the mother sharks were born in the wild, caught as young pups and then lived in captivity isolated from males of their species. Although sharks have been known to store sperm for as long as a year, Chapman points out that the pups were caught young and “glands that hold sperm at that age are not fully developed.” Last year, when Chapman and his colleagues studied the first sex-free birth in a bonnethead shark — a small type of hammerhead — he assumed it was a case of stored sperm until DNA fingerprint analysis showed there were no male contributions. Even then, he said, he still thought parthenogenesis “only happens as an occasional fluke.” He now thinks, “It’s definitely more common and widespread than we think.” Chapman is currently testing to confirm another reported case of parthenogenesis in a white spotted bamboo shark with Kevin Feldheim of the FieldMuseum in Chicago. “I think in the next five years we will be able to show many species of sharks — if not all — [have this ability],” says Chapman.