Peacock spiders’ superblack spots reflect just 0.5 percent of light

New images reveal microscopic structures that manipulate light to create the dark patches

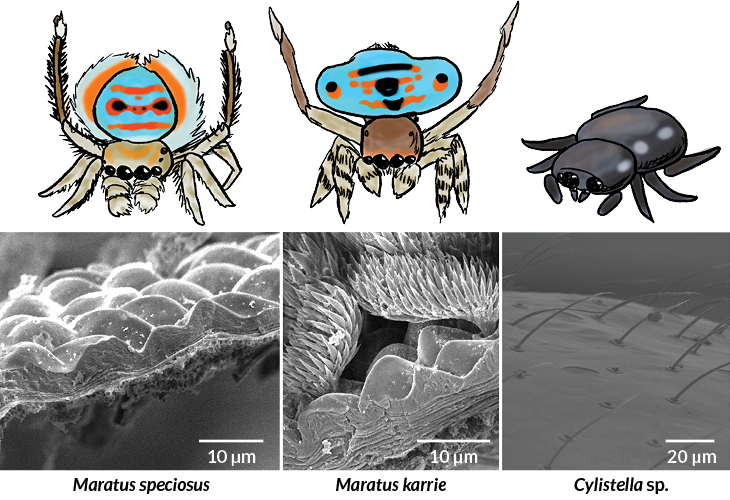

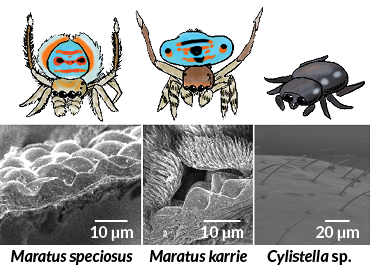

BLACK OUT Microscopic bumps on male Maratus speciosus peacock spiders (shown) make some of their black patches appear even darker, which may help the arachnids attract a mate.

Jürgen C. Otto