Sharing valuable real estate

Rewired areas of the brain retain their old abilities

Old brains can learn new tricks but retain their knack for lost senses.

A new study of two people who went blind while young and regained sight as adults shows that blind people’s brains remember how to see even when rewired for sound.

Scientists have known for some time that when a person loses a sense, the brain rewires itself to use parts previously dedicated to the lost sense. In blind people, for instance, vision centers can be remodeled to make sense of sound or turned into touch-processing areas.

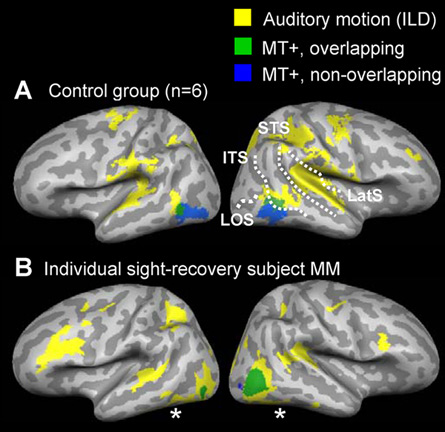

But rewired brains don’t erase the old vision-processing software. Instead, sight and sound processors occupy the same space in the brains of people with recovered vision, Melissa Saenz of the California Institute of Technology and her colleagues show in a study published May 14 in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Essentially, blind people’s brains allow hearing circuits to squat on territory normally reserved for vision, Saenz says — and that’s not surprising.

“This is a big part of the brain. It’s valuable real estate,” she says. “What we didn’t know was how these new functions move in.”

In order to find out, Saenz and her colleagues studied two people who regained sight as adults after many years of blindness: Mike May, 54, a businessman from California who lost his sight in a chemical accident when he was 3 years old; and a 53-year-old woman who was blind from a young age as a result of both retinopathy of prematurity and cataract growth. A cornea and stem cell transplant when May was 46 partially restored his vision in one eye. The woman had surgery to partially restore her sight at age 43.

Sighted people use a part of the visual cortex called MT+/V5 to see objects in motion. Other parts of the visual cortex are responsible for recognizing faces or stationary objects. Auditory motion, such as the sounds of a car driving past or footsteps retreating down a hallway, is deciphered by a network of brain areas, including an area adjacent to MT+/V5.

May and the other sight-restored volunteer used MT+/V5 for deciphering both visual and sound motion, but not speech or other types of sights or sounds.

That indicates that MT+/V5 shouldn’t be thought of as exclusively a visual area or an auditory area, says Alvaro Pascual-Leone, a neurologist at HarvardMedicalSchool in Boston who was not involved in the research. “It’s not a visual area per se; it’s a motion area.”

Learning how the brain uses its real estate may improve therapies for restoring vision and hearing, Pascual-Leone says. “Restoring visual input is not enough for seeing,” he says. The brain must also be prepared to handle the information.

May is still amassing an encyclopedia of clues to tell him what he sees. “It wasn’t until I had the operation, took the bandages off and started to see again that I was introduced to the intricacies of vision,” he says.

He can see colors. Motion is no problem. But he’s terrible with recognizing faces and objects.

“Why can I run and catch a ball, but I can’t recognize my wife’s face,” he wonders.

The researchers in the new study didn’t test how well the sight-restored people process motion information. It’s possible that having both senses integrated in a single area could improve motion detection, or it could hinder one or the other, says Franco Lepore, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Montreal.

He has studied similar phenomena in deaf people who have had

cochlear implants to help them hear again. Parts of the audio-processing areas

of deaf people’s brains get rewired to deal with vision. After hearing is restored,

competition in the auditory centers of the brain impair people’s ability to

decipher complex images while listening to sound, he says.

Regaining sight means getting another useful piece of

information about the world, May says, but he still uses sound and touch to

make sense of what he is seeing. And while the study shows that losing and

regaining his sight has changed his brain, May says the experiences haven’t

revolutionized his life.

“It’s life enriching. It hasn’t changed my life at all,” May says. “It’s like going to another country or meeting a really neat person. These things enrich your life, but they don’t change it in a profound way. Having vision is great, but being blind is great too.”