THE ZOO In 1835, the Gardens of the Zoological Society of London housed an assortment of exotic animals, many of which struggled to survive.

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

The Zoo

The Zoo

Isobel Charman

Pegasus

$27.95

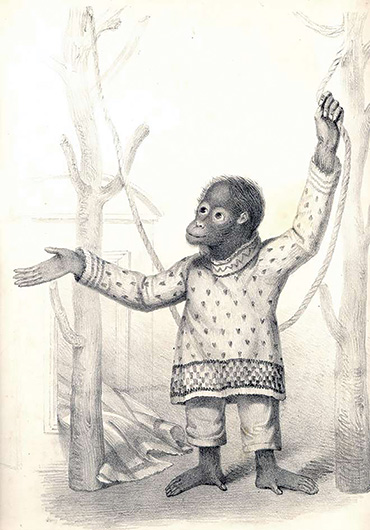

When Tommy the chimpanzee first came to London’s zoo in the fall of 1835, he was dressed in an old white shirt.

Keepers gave him a new frock and a sailor hat and set him up in a cozy spot in the kitchen to weather the winter. Visitors flocked to get a look at the little ape roaming around the keepers’ lodge, curled up in the cook’s lap or tugging on her skirt like a toddler. Tommy was a hit — the zoo’s latest star.

Six months later, he was dead.

Tommy’s sorrowful story comes near the middle of Isobel Charman’s latest book, The Zoo, a tale of the founding of the Gardens of the Zoological Society of London, known today as the London Zoo. The book lays out a grand saga of human ambition and audacity, but it’s the animals’ stories — their lives and deaths and hardships — that catch hold of readers and don’t let go.

Charman, a writer and documentary producer, resurrects almost three decades of history, beginning in 1824, when the zoo was still just a fantastical idea: a public menagerie of animals “that would allow naturalists to observe the creatures scientifically.”

It was a long, hard path to that lofty dream, though: In the zoo’s early years, exotic creatures were nearly impossible to keep alive. Charman unloads a numbing litany of animal misery that batters the reader like a boxer working over a speed bag. Kangaroos hurl themselves at fences, monkeys attack each other in cramped, dark cages and an elephant named Jack breaks a tusk while smashing up his den. Charman’s parade of horrors boggles the mind, as does the sheer number of animals carted from all corners of the world to the cold, wet enclosures of the zoo.

Her story is an incredible piece of detective work, told through the eyes of many key players and famous figures, including Charles Darwin. Charman plumbs details from newspaper articles, diaries, census records and weather reports to craft a narrative of the time. She portrays a London that’s gritty, grimy and cold, where some aspects of science and medicine seem stuck in the Dark Ages. Doctors still used leeches to bleed patients, and no one had a clue how to care for zoo animals.

Zoo workers certainly tried — applying liniment to sores on a lion’s legs, prescribing opium for a sick puma and treating a constipated llama with purgatives. But nothing seemed to stop the endless conveyor belt that brought living animals in and carried dead ones out. Back then, caring for zoo animals was mostly a matter of trial and error, Charman writes. What seems laughably obvious now — animals need shelter in winter, cakes and buns aren’t proper food for elephants — took zookeepers years to figure out.

Over time the zoo adapted, making gradual changes that eventually improved the lives of its inhabitants. It seemed to morph, finally, from mostly “a playground of the privileged,” as Charman calls it, to a reliable place for scientific study, where curious people could learn about the “wild and wonderful” creatures within.

Darwin’s work on the subject wouldn’t be published for decades, but in the meantime, the zoo’s early improvements seemed to have stuck. Over 30 years after Tommy the chimpanzee died in his keeper’s arms, a hippopotamus gave birth to “the first captive-bred hippo to be reared by its mother,” Charman notes. The baby hippo not only survived — she lived for 36 years.

Readers may wonder how standards for animal treatment have changed over time. But Charman sticks to history, rather than examining contrasts to modern zoos. Still, what she offers is gripping enough on its own: a bold, no-holds-barred look at one zoo’s beginning. It was impressive, no doubt. But it wasn’t pretty.

Buy The Zoo from Amazon.com. Sales generated through the links to Amazon.com contribute to Society for Science & the Public’s programs.