Tasmanian devils evolve resistance to contagious cancer

Genetic tweaks helping threatened marsupials beat deadly tumors

SURVIVAL GEAR Some genetic variants may have allowed a small number of Tasmanian devils to withstand a deadly contagious facial tumor that has killed up to 95 percent of them in some locales. The discovery could be good news for the species.

Chen Wu/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

A few Tasmanian devils have started a resistance movement against a contagious cancer that has depleted their numbers.

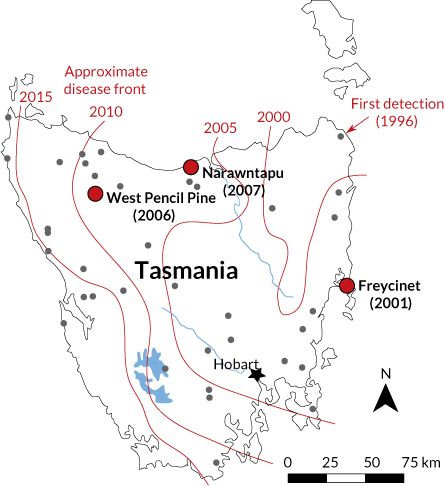

Since devil facial tumor disease was first discovered in 1996, it has wiped out about 80 percent of the Tasmanian devil population. In some places, up to 95 percent of devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) have succumbed to facial tumors, spread when devils bite each other. Scientists had believed the tumor to be universally fatal. But a new study finds that a small number of devils carry genetic variants that help them survive the disease — at least long enough to reproduce, researchers report August 30 in Nature Communications. The finding could be important for the survival of the species.

Previous studies have shown that the virulent tumor can hide itself from the devil’s immune system (SN: 4/20/13, p. 10). “What we reluctantly felt was that this was the end for the Tasmanian devil, because they really didn’t have a defense,” says Jim Kaufman, an evolutionary immunologist at the University of Cambridge not involved in the study. Indication that devils are evolving resistance to the deadly tumor “is really the most hopeful thing I’ve heard in a long time,” Kaufman says.

As the cancer spread across Tasmania, Menna Jones and colleagues collected DNA from devils in three populations before and after the disease arrived. Jones, a conservation biologist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart, then teamed up with evolutionary geneticist Andrew Storfer from Washington State University in Pullman. His team examined the devil genetic instruction book, or genome, to see if differences between devils before and after the tumor’s arrival could explain why some survived while the rest succumbed. Scientists had thought that surviving devils just hadn’t caught the facial tumor yet because they were too young to breed and get bitten, Kaufman says. The new analysis indicates that devils surviving after the facial tumor has wreaked havoc have a genetic advantage.

Storfer and colleagues found more than 90,000 DNA spots where a small number of devils have a different base (an information-carrying component of DNA) than most devils. The team looked for these genetic spelling differences — known as single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs — that had been rare before the tumor swept through a population but then became common. Such a pattern could indicate that natural selection was working, picking out variants that helped devils beat the tumor.

Two regions of the genome in all three of the devil populations contained SNPs that fit the profile. Because the two regions changed in all three populations, the change probably didn’t happen by chance, the researchers say. The resistance variants aren’t new mutations; there hasn’t been enough time for a helpful mutation to arise and spread across the island. Instead, the variants were probably already present in a small number of animals in the population and natural selection (via the tumor) weeded out the individuals that didn’t carry them.

Those two genome regions contain a total of seven genes, some of which have been shown to be involved in fighting cancer or controlling the immune system in other mammals. The researchers aren’t sure which genes boost survival in the devils or how they work. The variants don’t necessarily make devils completely immune to the tumor; the results would look the same if the variants just allow infected individuals to live long enough to pass along their genes, says Storfer. More undiscovered genes may also contribute to the devils’ survival, he says.

Researchers may be able to use genetics to better predict how the disease will spread in remaining uninfected devil populations. Breeding programs could incorporate animals that carry the survival variants to build the resistance movement.

Complicating matters is a second devil facial tumor, discovered last year. Researchers don’t know whether the variants that allow devils to resist the first facial tumor disease will also work against the second. That’s why comparative genomicist Katherine Belov at the University of Sydney says conservationists shouldn’t breed the resistance genes into all Tasmanian devils. Devils need all the genetic diversity they can get to cope with other diseases and unknown challenges down the line. Restricting breeding to animals that have these variants could limit the ability overcome future difficulties, she says.