Scientists have crunched the numbers for the September 2007 meteorite that landed in the Andes and suggest that the larger than normal impact crater resulted from the object’s unusually high speed.

Most stony objects that blaze through Earth’s atmosphere are blasted to bits by air resistance at high altitude (SN: 11/23/02, p. 323). Because the meteorite that struck eastern Peru on September 15 landed intact, its minerals must have been stronger than those typically found in similar extraterrestrial objects, says Peter Brown, an astronomer at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. He and his colleagues report the first comprehensive analysis of the 2007 impact in an upcoming Journal of Geophysical Research–Planets.

Data gathered by infrasonic sensors — part of the worldwide system designed to detect atmospheric pressure waves from nuclear explosions — indicate that the object entered the atmosphere from the east-northeast at a speed of around 12 kilometers per second.

By the time the object slammed into the high ground of the Andes — at an elevation of 3,800 meters, where the air is much thinner than it is at sea level — it probably was traveling no more than 4 kilometers per second, the researchers estimate. Still, the team’s analyses indicate that, had the object struck somewhere near sea level, air resistance would have further slowed the body’s speed to below 1 kilometer per second.

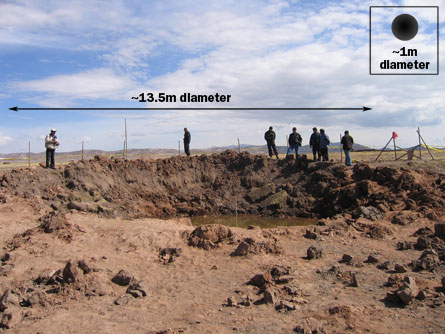

The meteorite probably measured about 1 meter across and weighed about 1.5 metric tons when it reached the ground. Because the impact speed of the object was abnormally high, the crater it gouged — about 13.5 meters across — was larger than the average crater created by a other meteorites of its size.

The energy released by the 2007 impact, which flung rocks and soil as far as 200 meters from the crater, was equal to that generated by exploding more than two tons of TNT, Brown and his colleagues estimate.