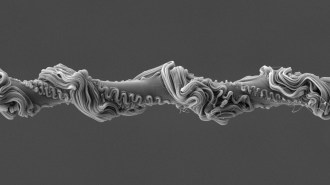

The New Holland honeyeater is a nectar-sipping bird from Australia. It can thrive on its sickeningly sweet diet due to genetic adaptations, changing the way its body responds to sugar.

© Gerald Allen

To eat a sugar-filled diet, birds had to evolve some sweet genetic tricks.

Birds that feed on nectar and fruits have important variants in genes that control metabolism, fat processing and even blood pressure. Findings published February 26 in Science show how different lineages of birds converged on similar genetic workarounds to let them live the high sugar life.

Several groups of birds have evolved to eat these sickeningly sweet diets, including parrots, hummingbirds, honeyeaters and sunbirds. “If [humans] are eating a lot of sugar, then a lot of bad things are happening to us: metabolic syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes,” says Ekaterina Osipova, a genomicist at Harvard University. “At the same time, there are birds that naturally solve this problem. They’re feeding on a lot of sugar, but nothing bad happens to them.”

Birds have fasting blood glucose levels 1.5 to two times as high as similarly sized mammals and are relatively insensitive to insulin. In mammals, insulin signals a protein called GLUT4 to move to cell membranes, helping the animals suck more sugar into their cells. But birds appear to lack this protein, so their blood glucose remains high.

As a result, while humans have sugar circulating in their blood, hummingbirds might as well have blood circulating in their sugar. Right after feeding, the tiny birds’ blood sugar spikes to around 757 milligrams per deciliter, says Kenneth Welch, a comparative physiologist at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study. That’s more than twice as high as a human’s blood sugar after a plate of pasta.

Osipova and her colleagues analyzed the genomes of birds with different diets to understand how some live successfully on so much sugar. They compared five sugar-feeding species, including representatives of the parrot, honeyeater and hummingbird families, with four species that prefer seeds, insects or meat, including the common swift and the brown thornbill. They also compared the transcriptomes — measures of which genes are actively being translated into RNA — from different tissues of three nectar-loving species and three nut- or insect-eating relatives.

They found thousands of sequences changed in nectar-eating birds. Most were in stretches of DNA that control how often other genes get transcribed and translated to proteins. But nearly 600 genes coded for proteins directly involved in processing sugar and fat.

Different groups of birds — like parrots and sunbirds — evolved similar differences in DNA due to their diets, the team found. And 66 protein-coding genes were changed in more than one of the high-sugar species.

But only one gene was altered in all four species, a gene called MLXIPL. “It serves as the cellular sugar sensor,” says Osipova. MLXIPL produces a transcription factor called ChREBP, which controls the activity of other genes. When Osipova and her colleagues put hummingbird MLXIPL into human cells, the cells changed the way they responded to sugar, activating genes to help the cells better metabolize carbohydrates.

Most of the changes across the nectar- and fruit-eating birds were in genes that control other genes, rather than those that make specific proteins. These changes are “tuning the system,” Welch says, helping the birds respond to the pressure of the high sugar diet by changing the responses of many genes at once.

The adaptations weren’t all about metabolism, says Chang Zhang, a physiologist at Sichuan University in China. Other alterations helped to control blood pressure. “This is a stunning example of evolutionary integration,” she says. “It suggests that evolving to thrive on a diet of nectar and fruit isn’t just about processing the sugar itself.”

Sugar is, after all, sticky, even in blood. At high levels, it can stick to other molecules. A nectar diet is also extremely watery. Both sticky sugar and a lot of water put demands on blood pressure. It’s vital to “keep the blood plasma just the right consistency, so that it doesn’t become too thick and lead to blockages,” Welch says.

Genes like MLXIPL could eventually become a clinical target for metabolic disease in humans, Osipova says, but that one gene alone isn’t enough. It takes a suite of genetic tweaks — changing everything from how cells sense sugar to blood pressure control — to survive the sweet life.