AI can measure our cultural history. But is it accurate?

Art and literature create a massive cognitive fossil record, hinting at past people’s psyches

New computational tools enable scientists to comb through large datasets of books, paintings, music and other art forms to understand past people’s psyches. This 1876 Renoir painting shows the life of leisure that emerged in France in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

The feelings, emotions and behaviors of people who lived in the past don’t leave a fossil record. But cultural artifacts, such as paintings, novels, music and other art forms, do. Now, researchers are developing tools to mine these artifacts to decipher how people in past societies might have thought and felt.

Consider Hieronymus Bosch’s famous circa 1500 painting “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” with its fantastical creatures, a potential metaphor for exploration and discovery characteristic of the period. Or “Dance at the Moulin de la Galette,” Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s impressionist 1876 painting of a Parisian dance hall depicting the emerging life of leisure and prosperity during the Belle Époque. Conversely, Vincent van Gogh’s 1885 painting “The Potato Eaters” shows a darkened room with coarse-faced peasants, a symbol of rural poverty. And Pablo Picasso’s 1937 stark painting “Guernica” uses disembodied figures to convey the horror of the Spanish Civil War.

Some researchers call these relics “cognitive fossils.” Digging for them in cultural artifacts was once a painstaking endeavor, largely done by humanities scholars. But with advances in computing and artificial intelligence, other researchers now are jumping into the fray, digitizing historic material spanning hundreds or thousands of years and developing algorithms capable of identifying patterns in those enormous cultural datasets.

“We can get to know more about the psychology of people who lived before us,” says Mohammad Atari, a social psychologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

The hope is that this deep dive into the past will lead to more generalizable theories about human behavior. A push to expand the scope of psychology began with efforts to include research participants from outside the West. But to really understand human behavior, researchers must look across both space and time, Atari and colleagues argue in June in Nature Human Behaviour. Historical psychology has the potential to show how societal norms and transformations influenced people’s mindsets, he says.

While groundbreaking, such work must be approached with caution, researchers note. It’s too easy to rely on machines, instead of human experts, to interpret, or misinterpret, patterns, for instance. And, much like the physical fossil record, the cognitive fossil record has gaps. Only some members of society had the luxury to pay for books, listen to music or spend time admiring paintings, says Nicolas Baumard, a psychologist at the Université PSL in Paris. “What we are studying is a fraction of humanity.”

Reducing psychological myopia

Early efforts to zoom out beyond the present mostly began with textual analyses. Since the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press in the 1400s, humans have produced at least 160 million unique books, Atari and his team note.

More than a decade ago, Chinese philosophy and comparative religion expert Edward Slingerland showed how to take advantage of that text and computation to answer a longstanding debate among Chinese scholars: whether or not ancient Chinese people distinguished between mind and body, with ample evidence for both sides. Slingerland, of the University of British Columbia in Canada, and colleagues looked for references to xin, which loosely translates to “heart,” in an online databasefrom pre-Qin China, or pre-221 B.C. That yielded over 600 ancient Chinese texts. Coders selected 60 passages at random and created classifications for the context in which xin appeared. In particular, they noted when xin contrasted with words used to refer to the body. Coders then applied that classification to the remaining passages.

The terms for heart and body co-occurred in a way that made clear that early Chinese people did distinguish between the two phenomena, Slingerland and a colleague reported in 2011 in Cognitive Science. At that point, debate was over, Slingerland says. “We … have overwhelming evidence that the dualist position is the right one because of these patterns in the text that you can’t explain any other way.”

Texts can also reveal the evolution of romantic love in fiction and what that might say about people’s changing psychologies over time, Baumard says. His team manually combed through lists on Wikipedia related to “history of literature” to create a database of literary summaries spanning 3,800 years. The researchers then automated the process of counting terms such as “love,” “lovesick” and “star-crossed” in those summaries to see how much those references increased over time. Their findings lent support for a longstanding hypothesis in the humanities — that economic growth caused an increase in romantic love stories, the team reported in April 2022 in Nature Human Behaviour.

Affluence enabled people to think beyond survival, to aspects of human flourishing, including love, Baumard says. The field is moving fast, though. And now, Baumard and his team want to replicate the earlier result using modern artificial intelligence tools, such as large language models.

Moving beyond words

Art forms besides text also leave quantifiable, albeit harder-to-detect, psychological signatures. It’s possible paintings reflect societal transformations, such as political transitions, climate change and the impact of trade.

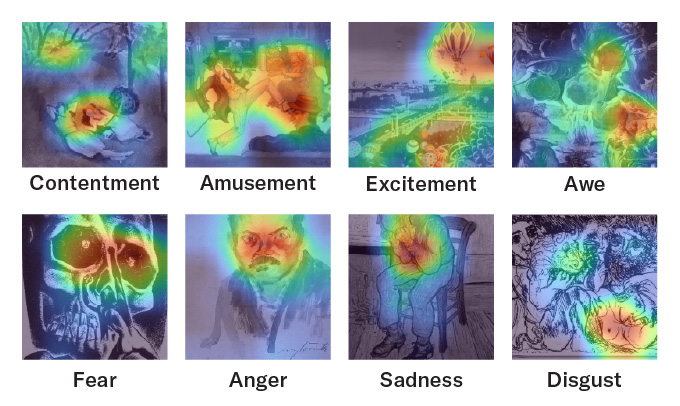

To take a closer look, a team of economists built on previous work in which 20 screeners identified the emotions in roughly 80,000 paintings. They could choose from nine emotions: contentment, amusement, excitement, awe, fear, anger, sadness, disgust and other. The economists used the screeners’ judgments to train the AI to predict the emotions in paintings on Google Arts and Culture, Wiki Data and Wiki Art — a combined dataset dating back to 1400 and consisting of almost 631,000 paintings from over 29,000 artists.

The team also trained the AI on the way details in a picture combine to create emotions. Those combinations closely resembled known building blocks of art. “Our algorithm is founded on art theory,” says Stephan Heblich of the University of Toronto.

Heat maps showing what the AI focused on to determine emotions revealed that the model was able to zoom out from such details as lines and textures to focus on emotionally complex aspects of the painting, such as facial expressions and weapons. In other words, the model taught itself to see like a human.

Emotions did map onto historic events, the team’s preliminary findings show. During the Little Ice Age from roughly 1500 to 1700, for instance, increasing temperatures correlated with decreasing fear and sadness in paintings. Zooming in on Germany, positive emotions, such as contentment and excitement, peaked around 1850 and then began a long decline that only reversed after World War II.

The paper provides a proof of concept that paintings do leave a discernable emotional signature, Heblich says. Longer term, the team hopes to identify more subtle signatures in paintings, such as the emotional imprint of inequality from the perspective of the haves and have-nots in a given society.

When advancements break down

Machines are only as good as the information humans feed them. And keeping experts in the loop during coding and analysis is key to getting this process right, say Slingerland and others. Their main criticism is directed at a now-retracted study in Nature.

Scientists on that paper used a big data approach to see if belief in moralizing gods, or all-seeing gods that reward good behavior and punish bad behavior, came before or after the emergence of large, complex societies. The researchers analyzed historical data dating back 10,000 years on over 400 societies from 30 world regions. They also input dozens of measures of social complexity and expert opinions on when moralizing gods first appeared in a given region. Moralizing gods came after, not before, the emergence of complex societies, the team reported in 2019 — a finding that contradicted prevailing wisdom.

Scientific and humanities scholars quickly questioned the results. For instance, Slingerland and his team published a rebuttal, now forthcoming in the Journal of Cognitive Historiography, noting that the team’s coders consisted primarily of research assistants unfamiliar with religious history. As such, the coders occasionally relied on minority opinions or selected arbitrarily among competing theories,” Slingerland says. “They were parachuting into the literature.”

He remains optimistic about the tools’ potential, though. When done right, the ability to interrogate these enormous cultural datasets could make the humanities much more progressive, he says. “I feel like [humanities scholars] get stuck in these loops … This is a way to ideally settle some of these debates and then move forward.”