Students’ mental health imperiled by $1 billion cuts to school funding

Cutting mental health services will harm students over the long term, educators say

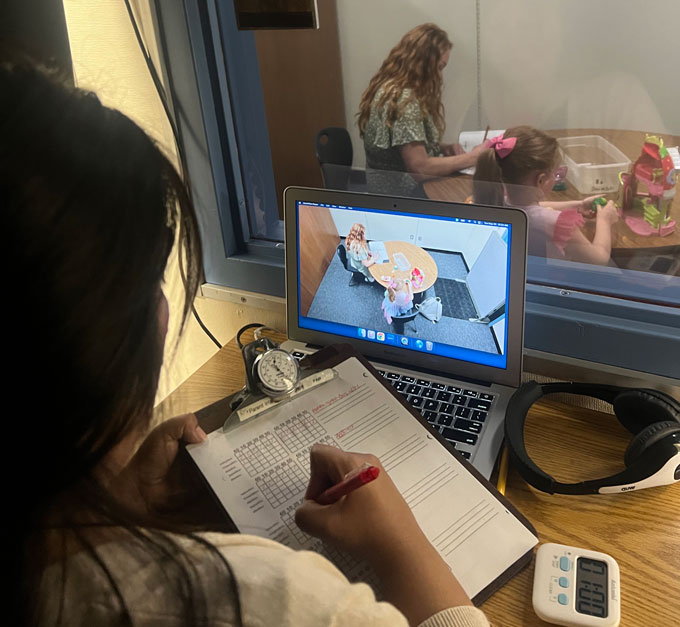

The Parent Empowerment Program, or PEP, at La Mesa–Springs Valley School District in San Diego helps caregivers and their children work through various challenges. Here, mother Janet Walton leads a group activity aimed at helping children share. That includes Walton’s son, Elijah, who is passing a toy to a peer.

LMSVSD PEP

Four-year-old Elijah’s task was to draw a penguin, his favorite animal, and then rip up the paper so the scraps could be used for another project. The adults leading the project hoped that making Elijah uncomfortable would help the preschooler navigate similar tricky situations in his daily life.

“He was not having it,” recalls Elijah’s mother, Janet Walton. “He freaked out.”

For most toddlers, ripping up a beloved drawing would be a challenging ask. But Elijah’s struggles went beyond the norm. After a particularly bad tantrum at public preschool last year, a mental health expert with the La Mesa–Spring Valley School District in San Diego referred Walton to the Parent Empowerment Program, or PEP.

Provided free of charge by the district, PEP helps children up to age 6 and their caregivers work through behavioral and emotional challenges. Some children, like Elijah, who is now 5, come in without a diagnosis. (He has since been diagnosed with oppositional defiance disorder, which is characterized by frequent outbursts and defiance toward caregivers.) Others enter the program with known challenges. Four-year-old Bertie, for example, is on the autism spectrum. Like many children with the disorder, Bertie has few words and struggles in social settings, says her mother, Grindl McMahon.

But in late April, the Trump administration sent out letters terminating roughly $1 billion in funding for student mental health grants given to school districts, education agencies and universities. The grants were discontinued due to their focus on increasing the diversity of mental health providers, an education department spokesperson said. PEP is on the chopping block, along with other similar programs nationwide, as well as funding for school mental health providers and those receiving training for such jobs.

“We are talking about critical services to kids,” says Deann Ragsdale, La Mesa–Spring Valley’s deputy superintendent of educational services. Losing this funding “has knocked the wind out of us.”

Bipartisan support

The terminated grant money largely came out of the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. That act was passed on the heels of the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, where a shooter killed 19 elementary school students and two teachers and injured 17 others. Proponents of the bill hoped that the money would help alleviate the ongoing youth mental health crisis, which experts say has been exacerbated by excessive or inappropriate technology use and pandemic-related learning disruptions. A recent report showing that over half of teenage girls and a third of teenage boys struggle with feelings of “sadness and hopelessness” raised alarm bells among experts and caregivers across the nation.

Providing mental health services in schools allows struggling children and their families to receive help immediately, says Prerna Arora, a psychologist at Teachers College, Columbia University. “There’s a lot of long-term negative consequences to having untreated mental health concerns.” Those consequences include intensifying symptoms over time, missed school and underemployment or unemployment in adulthood, she says.

Emotional challenges have wide-reaching effects, Ragsdale adds. When even one child struggles, that can affect all their peers in the classroom.

The executive order means that many schools and agencies will never apply for or receive funding. Places that have received grants will probably see their funding cut off midstream or when the grants terminate in December.

Many districts and agencies have been using the money to increase the number of school mental health care providers. But with such providers in short supply, grants have also gone toward training more school-based mental health care providers.

Education experts recommend at least one social worker for every 250 students and one school psychologist for every 500 students. Though job descriptions vary by district, school psychologists tend to focus on special education, including assessing students’ eligibility, while social workers help connect students and families to community resources. Both psychologists and social workers deliver small group and individual counseling.

The vast majority of school districts across the country are unable to provide those and other mental health supports, research shows. For instance, for the 2023–2024 school year, on average one school psychologist served 1,065 students, according to the National Association of School Psychologists.

A school district in Rochester, Minn., for example, received roughly $228,500 in December 2022 to help fill a shortage of mental health care providers. The district’s primary goal was to use the funding to pay for degrees in student mental health care for individuals already working within the district. “Increasing staffing in this way will move the district closer to the professional recommendation of 250:1 student to school social worker ratio from the current baseline of 414:1,” applicants wrote in the grant proposal.

The provider shortage is even more severe in rural and lower-income districts. For instance, Cochise County in Arizona spans more than 15,000 square kilometers — an area roughly equal to that of Connecticut and Rhode Island combined — and encompasses a mix of border cities, a military base and rural agricultural areas. Yet the county has only 12 mental health providers for over 9,500 students, meaning a single provider sees over 800 students. With the help of a five-year, nearly $1.8 million grant beginning in January, the county hoped to hire nine more mental health professionals to reduce that ratio to 459 students per provider.

Teachers College, Columbia University similarly applied for and received a five-year, 4.9 million grant last year, with roughly $915,000 awarded the first year, Arora says. The goal was to train 32 master’s students in school psychology. In exchange for tuition, the students would agree to work at high-needs schools across New York City as part of their training and after graduation.

In March, program administrators received a letter stating that funding for the program had been cut, effective immediately. The school scrambled to find funding for the five students who started in January. Additionally, the school had just admitted 11 new students for the fall but had to tell them that funding would no longer be available. Four students accepted the offer, Prerna says. But without that funding, students will not receive fieldwork experience at a high-needs school, nor are they obligated to work at that school upon graduation.

Integrating education and mental health

Until a few decades ago, education and mental health care largely operated in silos. Doctors directed children with behavioral challenges to community mental health services. But such services were, and still are, underfunded and fragmented.

Ragsdale says that when she arrived at La Mesa–Springs Valley seven years ago, a shortage of trained mental health experts within the district meant that students got referred to community health clinics. There, they often got lost trying to navigate the system on their own. Others encountered monthslong wait times to see anyone.

Those gaps in care led to a proliferation of school-based mental health centers across the country by the 1990s. Teachers were well-positioned to identify students with existing problems or those who were starting to slip through the cracks, experts realized. And mounting evidence showed that improving a child’s mental health also led to improved attendance and grades.

Best practices today emphasize comprehensive care divided into tiers. At the lowest level, or Tier 1, are supports that benefit all students, such as those related to social, behavioral and emotional learning. Tier 2 supports are for students struggling with mild distress and can include small-group therapies or brief one-on-one counseling or coaching. Tier 3 services tend to be intensive and individualized to meet the needs of a given student.

The hope is that increasing access to Tier 1 and 2 services, or helping students before their problems worsen, will lower the need for Tier 3 services, Arora says.

Back in San Diego, Ragsdale isn’t sure what to do now. California law requires that districts tell employees by mid-March if they won’t have a job in the coming school year. But this round of cuts was announced in April, leaving her with employees for whom she needs to find funding before their pay runs out in December. “This is creating a $2.5 million hole,” Ragsdale says.

Money aside, parents wonder how they will manage without programs like PEP, which brings caregivers and students into special settings for four hours per week over several months. Once the more intense treatment phase is over, caregivers pay it forward by teaching what they’ve learned to new families.

Both McMahon and Walton say that PEP has been invaluable in helping their children manage their emotions, even in the most trying circumstances. McMahon, for instance, realized the extent of the service’s impact during their annual outing to the town’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade this year. Instead of throwing a tantrum or wandering off, as in previous years, McMahon says Bertie was engaged with the family and enjoying herself. “[PEP] has just been monumental in our family dynamic,” McMahon says. “Things like this shouldn’t be cut.”