Chess players rely on familiar moves even when the game changes

People use past experiences to guide decision-making, even when the present is unprecedented

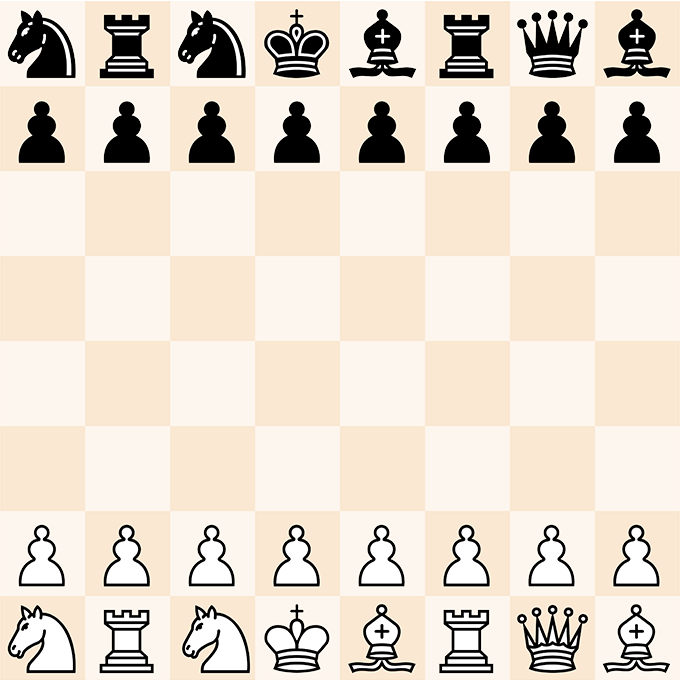

Well-executed starting moves in chess can tip a game’s outcome, and players often rely on tried-and-true openers. Those openers may not work well in Chess960, a chess variant that scrambles the pieces, but players tend to use them anyway.

Pannonia/Getty Images

Last year, my son joined the middle school chess club and began using me, a total novice, as his sparring partner. In chess, a player can choose from one of 20 opening moves, including moving a knight in the back row to one of four possible spots or any of the pawns in the front row one or two spaces forward. That opening matters a lot, determining how the game unspools and, ultimately, a player’s odds of winning. I experimented wildly, including with oddball moves, such as moving the pawn on the far right a single space forward. Given how badly that game went, I never used that opener again.

Yet an opening move with a low probability of success in conventional chess might be a winner in Chess960, a decades-old variant of the classic game. In Chess960, pawns still line the front row, but the back pieces are scrambled (though in the same formation for both black and white pieces). It’s a topsy-turvy chess universe where players often rely on tried-and-true opening moves, even when an oddball move might yield greater success, researchers reported earlier this month in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

The findings hint at how to make decisions when life doesn’t seem to be playing by the rules.

“One would expect that if the situation changes, then decision makers would go back to the drawing board, so to speak, and adjust their choices,” says Yuval Salant, a behavioral scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. The cost of relying on past experiences when other approaches might make more sense is called the “memory premium.” In chess, at least, this premium is quantifiable.

To calculate these premiums, Salant and his colleagues analyzed games played from January 2013 to June 2021 on lichess.org, a popular internet chess server where players can play either the standard or scrambled version of the game.

The researchers first excluded less experienced players, or those who had opened fewer than 20 times in standard chess on Lichess. They then zoomed in on the opening moves of roughly 147,000 players trying Chess960 for the first time while playing with the white pieces, which go first.

In standard chess, any move has a 1 in 20 — or 5 percent — chance of being selected on average, though some opening moves are more popular than others. Salant and his colleagues counted any move that a player had opened with in standard chess as stored in memory. In Chess960, a player’s likelihood of starting with a given in-memory move increased by roughly 4 percentage points, on average, over that 5 percent baseline, the team found.

For instance, moving the pawn in front of the queen two squares forward, from D2 to D4, is a popular chess opener. About three-quarters of the players in the study, roughly 110,000 individuals, had opened with D2 to D4 in standard chess. Of those players, 20 percent opened with that same move in their first game of Chess960, regardless of which piece started behind the D2 pawn, the team found. Among players who had not used that move in standard chess, the likelihood of opening with it in Chess960 dropped to 10 percent. In other words, having that move in memory doubled the chance that a player would use it in an off-kilter setting.

Using a program called Stockfish, which can rate the value of every move in chess or Chess960, the team also scored the opening moves. Moves in memory often had lower scores than the best alternative, the team found. But unlike Stockfish, naïve players cannot see the statistical chances of eventual success for different openings. As such, memory served as a reasonable way to select a sufficiently high-scoring opening move — to a point. When the scrambled board deviated substantially from the standard arrangement, shifting from memory to rational analysis would have yielded better odds of winning.

In wholly new situations, it’s worth “thinking beyond intuition,” Salant says.

And experience helped. When the team focused on the roughly 16,700 players who had played Chess960 at least 50 times, they found that the memory premium dropped from roughly 4 percentage points to 2.5 percentage points, suggesting that people were starting to think outside the box.

In fact, legendary chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer invented Chess960 in 1996 to get players outside their comfort zone, Salant says. “He thought chess is not about memorization but … strategic thinking.”

The findings suggest that memory, while imperfect, is usually a decent shortcut for decision-making, says Michael Woodford, a behavioral economist at Columbia University who was not involved with this research. And when things feel wholly unprecedented, reflecting on similar situations across time or space — or gaining the chess equivalent of experience, rather than turning to a familiar but less relevant playbook — isn’t a bad idea. “This seems to be an important lesson about real life,” Woodford says.