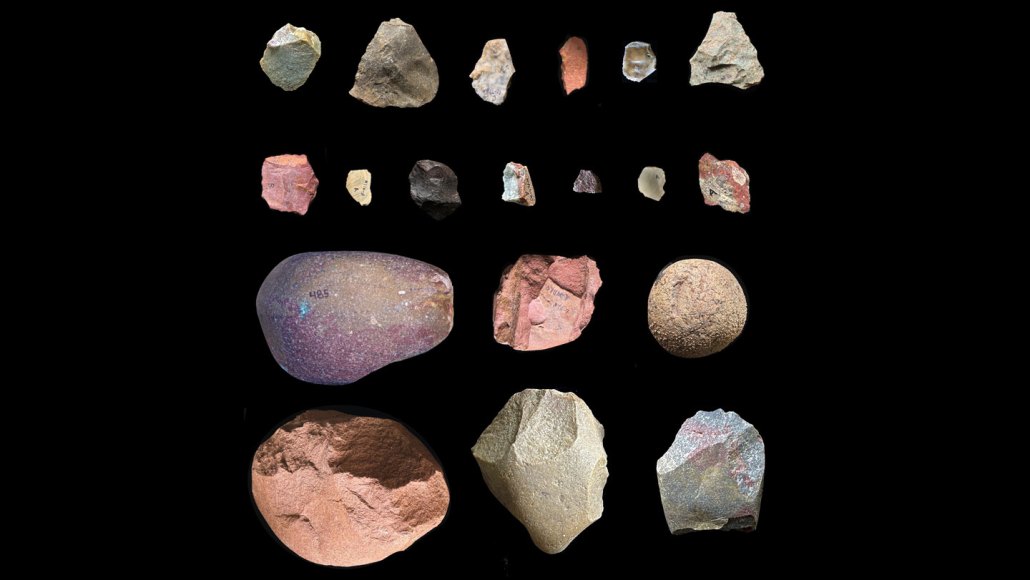

Ancient hominids made long road trips to collect stone for tools

Our ancestors were traveling up to 13 kilometers at least 2.6 million years ago

Ancient hominids transported high-quality rock a surprisingly long way — up to 13 kilometers — to make stone implements, including the ones shown here, at least 2.6 million years ago, researchers say.

E.M Finestone, J.S. Oliver, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project