This scallop has blue eyes that help it to see, but its vision is very different from how humans see the world.

Little Dinosaur/Moment Open/Getty Images Plus

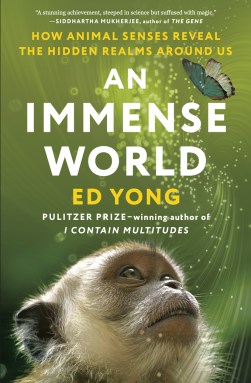

An Immense World

Ed Yong

Random House, $30

Emerald jewel wasps know what cockroach brains feel like.

This comes in handy when a female wasp needs to turn a cockroach into an obedient zombie that will host her larvae and serve as dinner. First, the wasp plunges its stinger into the cockroach’s midsection to briefly paralyze the legs. Next comes a more delicate operation: stinging the head to deliver a dose of venom to specific nerve cells in the brain, which gives the wasp control over where its victim goes. But how does a wasp know when it’s reached the brain? The stinger’s tip is a sensory probe. In experiments using brainless cockroaches, a wasp will sting the head over and over again, searching fruitlessly for its desired target.

A brain-feeling stinger is just one example of the myriad ways animals sense the world around them. We humans tend to think the world is as we perceive it. But for everything that we can see, smell, taste, hear or touch, there’s so much more that we’re oblivious to.

In An Immense World, science journalist Ed Yong introduces that hidden world and the concept of Umwelt, a German word that refers to the parts of the environment an animal senses and experiences. Every creature has its own Umwelt. In a room filled with different types of organisms, or even multiple people, each individual would experience that shared atmosphere in wholly different ways.

Yong eases readers into the truly immense world of senses by starting with ones that we are intimately familiar with. In some cases, he tests the limits of his own abilities. Dog noses, for instance, are better than human noses at sniffing out a scent long after the source is gone, as Yong demonstrates. While crawling around on his hands and knees with his eyes closed, he was able to track a chocolate-scented string that a researcher had put on the ground. But he lost the scent when the string was removed. That wouldn’t happen to a dog. It would pick up the trace, string or no string.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

In exploring the vast sensory world, it helps to have a good imagination, as even familiar senses can seem quite strange. Scallops, for instance, have eyes and somehow “see” despite having a crude brain that can’t process the images. Crickets have hairs that are so responsive to an approaching spider that trying to make the hairs more sensitive might break the rules of physics. A blind Ecuadorian catfish senses raging water with durable teeth that cover its skin. The animal uses the dentures to find calmer waters.

Going through these imagination warm-up exercises makes it somewhat easier to ponder what it might be like to be an echolocating bat, a bird that detects magnetic fields or a fish that communicates using electricity. Yong’s vivid descriptions also help readers fathom these senses: “A river full of electric fish must be like a cocktail party where no one ever shuts up, even when their mouths are full.” In a forest, foliage may seem largely silent, but some insects “talk” through plant stems using vibration. With headphones hooked up to plants so that scientists can listen in, “chirping cicadas sound like cows and katydids sound like revving chainsaws.”

For all the book’s wonder, the last chapter brings readers crashing back to today’s reality. Humans are polluting animals’ Umwelten; we’re forcing animals to exist in environments contaminated with human-made stimuli. And the consequences can be deadly, Yong warns. Adding artificial light in the darkness of night is killing birds and insects (SN: 8/31/21). Making environments louder is masking the sounds of predators and forcing prey to spend more time keeping an eye out than eating (SN: 5/4/17). “We are closer than ever to understanding what it is like to be another animal,” Yong writes, “but we have made it harder than ever for other animals to be.”

Since each of us has our own Umwelt, fully understanding the foreign worlds of animals is close to impossible, Yong writes. How do we know, for instance, which animals feel pain? Researchers can dissect the signals or stimuli an animal might receive. But what that creature experiences often remains a mystery.

Buy An Immense World from Bookshop.org. Science News is a Bookshop.org affiliate and will earn a commission on purchases made from links in this article.