MONARCHS IN WINTER Declines in the numbers of monarch butterflies crowding into winter refuges in Mexico (shown) raise the question of what’s going on the rest of the year.

Pablo Leautaud/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

A fuss over trends in monarch butterfly populations has flared up with a flurry of new research papers, all based on records from volunteer butterfly watchers.

There’s no dispute that numbers of monarch butterflies are dwindling at winter refuges in central Mexico (SN: 4/23/11, p. 18). But eight papers published online August 5 in Annals of the Entomological Society of America split over the reason why.

In one view, the monarch population that summers east of the Rockies is shrinking year-round, not just in winter. In the butterfly breeding heartland of the U.S. Midwest, the decline may come from loss of the milkweeds that caterpillars need for food, explains Karen Oberhauser of the University of Minnesota in St. Paul. It takes about 29 milkweed plants, Oberhauser’s team has found, to produce a caterpillar that grows up to fly off toward Mexico. But the once-common plants are growing scarcer as farmers intensify weed control for genetically modified corn and soybeans engineered to tolerate herbicides.

Two papers from Oberhauser’s Monarch Lab report signs of trouble — sparser egg laying and rising mortality among caterpillars from 1997 to 2014— for monarchs breeding in farm country.

In contrast, Andrew K. Davis of the University of Georgia in Athens counters that monarchs might be reproducing well enough during spring and summer in the United States and Canada. His controversial scenario pins the missing Mexico monarchs to failures in migrating to the oyamel fir forests in the Sierra Madre Mountains. With logging and encroaching development, “maybe it doesn’t look like it used to,” he says.

Story continues below infographic

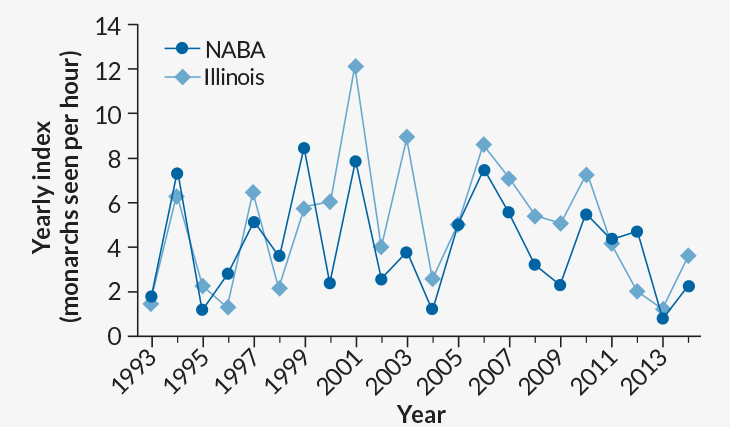

Ups and downs

No overall trend appears in surveys of monarch sightings (number of butterflies seen per hour) from two volunteer groups, the North American Butterfly Association and the Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network, over the last 22 years. A possible downturn near the end bears watching in future years, researchers say.

Credit: Graph: L. Ries, D.J. Taron, E. Rendón-Salinas /Annals Ent. Soc. Am. 2015

The monarchs that migrate south in the fall have never made the trip before. (The round-trip migration occurs over three or four generations, so it’s often their great-grandparents that started the journey north at the end of the previous winter.) Cues for newcomers finding and settling in the right spot may be weakening, Davis says.

No single monitoring program gives the whole picture of how generations of monarchs recolonize half a continent each year. But Davis says five geographically scattered butterfly watches report no long-term declines in breeding season adults. In one study, he and Gina Badgett of the Peninsula Point Monarch Monitoring Project in Rapid River, Mich., find no declining trend in 19 years of fall monarch counts. And another study reports that the butterflies’ geographic range has not diminished in 18 years of sightings of the season’s first adult monarchs reported to the Journey North database. That stability suggests the population hasn’t changed much in numbers, Davis and Journey North founder Elizabeth Howard report.

But first sightings are not a good measure for trends in population size, says ecologist John Pleasants of Iowa State University in Ames. “Monarchs are excellent long-distance fliers and even a sparse population could cover the typical range,” he says. The apparent absence of very steep downward trends in the new bunch of papers doesn’t soothe the worries of longtime monarch researcher Lincoln Brower of Sweet Briar College in Virginia. He points out that, not surprisingly, volunteers in broad monitoring programs like that of the North American Butterfly Association often go to count butterflies at places that still have them, making it difficult to detect population changes.

Leslie Ries, an ecologist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., predicts that applying more sophisticated analyses of citizen science data could eventually pick out trends. She and her colleagues found population peaks and plunges but no strong decline or increase in 22 years of monarch reports from two independent butterfly censuses (an Illinois program and the North American Butterfly Association’s seasonal count). Ries is cautious about pulling trends out of such fluctuating data and notes there might be hints of possible declines toward the end of the time period. Davis, however, sees Ries’ results as an absence of decline. Out of all the new papers, he predicts, it is “probably going to be the most shocking piece of news.”

Oberhauser says fallout from the debate could be more shocking. “I hope people don’t take away from this that monarch numbers aren’t declining,” she says. Researchers agree something is going wrong. The discussion is over when, where and why.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on August 13, 2015, to remove the butterfly images from the graph.