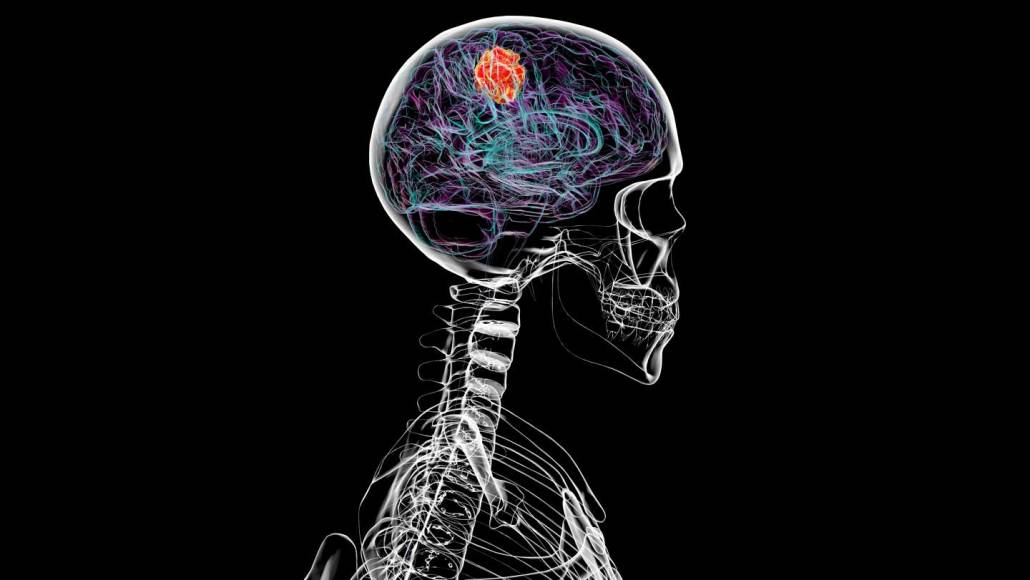

A type of brain cancer called glioblastoma, shown in this illustration, can thin the bones of the skull in mice and people.

Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

It sounds like something from a horror movie: A disease that eats through bone, dissolving the fused plates of the skull like bubbling acid.

But a type of brain cancer called glioblastoma actually does something similar, triggering the erosion of living skull tissue, researchers report October 3 in Nature Neuroscience. The work shows in gory detail that brain cancer can erode bone, a harmful effect that wasn’t previously known, says Jinan Behnan, a brain tumor immunologist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Bronx, New York.

Behnan’s findings uncover a creepy new facet of glioblastoma, an enigmatic cancer still cloaked in scientific questions. “We really still don’t understand exactly what this disease is,” she says.

Glioblastoma is an aggressive form of brain cancer that’s particularly lethal and nearly impossible to cure. In the United States, doctors diagnose more than 12,000 new cases every year. Five years after diagnosis, only about five percent of patients over 40 years old survive.

Doctors urgently need new treatments, Behnan says. She first started studying glioblastoma more than a decade ago as a master’s student in Sweden. While dissecting the skulls of diseased mice, her scissors sliced easily through the bone, like cutting through a shrimp shell. “This is strange,” she remembers telling her mentor. The animals’ skulls felt softer and thinner than those of mice without brain cancer. At the time, she wasn’t able to investigate the finding. But the idea stuck with her.

Now, she’s discovered why those skulls likely seemed flimsy: glioblastoma had thinned the bone. 3-D X-ray imaging of mice with brain cancer revealed the skullduggery. Along the skull’s suture lines, where babies’ separate plates of bone knit together, Behnan’s team observed prominent erosion. The bone looked worn away, like a decayed tooth. The researchers saw something similar in scans of human patients with the disease — an average of 20 percent loss of bone thickness in the skull.

In mice with brain tumors, researchers traced the skull thinning to increased activity of bone erosion cells, which typically play a role in bone remodeling. And the researchers uncovered another anomaly, too: a dramatic change in the composition of immune cells populating the skull marrow. Behnan doesn’t know yet how this factors into the bone loss her team observed, or whether brain cancers gain something from dissolving the skull.

The team thought the cranial thinning might fuel tumor growth by letting the cancer tap into marrow-rich bone. But experiments to block bone erosion backfired, prompting mice’s brain tumors to progress even faster. It’s a mystery the researchers need to keep investigating, Behnan says.