China’s lunar rover may have found minerals from the moon’s mantle

New observations could answer questions about how Earth’s nearest neighbor evolved

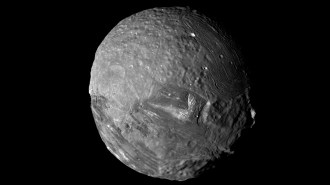

INSIDE OUT China’s Chang’e-4 mission, which landed in a massive impact basin on the farside of the moon (pictured in false-color blue and purple hues) in January, has detected what appears to be lunar mantle material on the moon’s surface.

NASA/GSFC/Univ. of Arizona

The first mission to the farside of the moon may have found bits of the moon’s interior on its surface.

The Yutu-2 rover, deployed by the Chinese Chang’e-4 spacecraft that landed on the moon in January, detected soil that appears rich in minerals thought to make up the lunar mantle, researchers report in the May 16 Nature. Those origins, if confirmed, could offer insight into the moon’s early development.

“Understanding the composition of the lunar mantle is key to determining how the moon formed and evolved,” says Mark Wieczorek, a geophysicist at the Côte d’Azur Observatory in Nice, France, not involved in the work. “We do not have any clear, unaltered samples of the lunar mantle” from past moon missions.

In hopes of finding mantle samples, Chang’e-4 touched down in the moon’s largest impact basin, the South Pole–Aitken basin (SN: 2/2/19, p. 5). The collision that formed this enormous divot is thought to have been powerful enough to punch through the moon’s crust and expose mantle rocks to the lunar surface (SN: 11/24/18, p. 14). During its first lunar day on the moon, Yutu-2 recorded the spectra of light reflected off lunar soil at two spots using its Visible and Near-Infrared Spectrometer.

When researchers analyzed these spectra, “what we saw was quite different” than normal lunar surface material, says study coauthor Dawei Liu, a planetary scientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing.

“There need to be some follow-up observations” to confirm that this material really is from the mantle, says Daniel Moriarty, a lunar geologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., not involved in the work. That’s because other materials in the lunar crust, such as plagioclase, can create spectral signatures similar to those of olivine.

Yutu-2 could identify mantle material more conclusively by examining the spectra of specific rocks, rather than mineral mixtures in soil, says Jay Melosh, a planetary scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., not involved in the study. “It would really be best if we could have samples back on the Earth” for lab analyses to tease apart different mineral components.

The Yutu-2 rover will continue investigating candidate mantle materials on the moon in preparation for a potential future sample return mission to Earth, the researchers say.

If from the mantle, the material’s chemical makeup could help clarify the moon’s early history. Billions of years ago, scientists think, the moon was partially or completely molten. As the moon cooled and solidified, materials of different densities separated into the mantle and crust. “We’re currently in this stage where we have a lot of different models” for how this crystallization process occurred, Moriarty says. These models predict different abundances of minerals like olivine and pyroxene in the upper mantle. Samples of the lunar interior could help determine which models best describe how the moon evolved.

A more detailed picture of the moon’s interior may also shed light on planetary evolution in general, says Briony Horgan, a planetary scientist at Purdue not involved in the research. Unlike Earth, the moon doesn’t have tectonic plates that shuffle surface material around or draw ocean water into the mantle when they slip underneath one another (SN Online: 5/13/19). The moon offers “a unique window” into the inner workings of a planetary body that’s quite different from Earth, she says.